Alfonso XIII y El Automóvil

(Spanish) It is well known that the automobile was not universally embraced in its early days. This perspective from W.O. Bentley’s 1967 autobiography, My Life and My Cars (978-0090841509), captured the sentiment: “The motor car seemed to me a disagreeable vehicle. Perhaps I should have realised the vast potentialities of internal combustion and recognised from my nursery days that it was to be the impelling force in my life. But the fact must be recorded that the motorcar struck my young, literal mind as slow, inefficient, draughty and anti-social means of transport. Motor cars splashed people with mud, frightened horses, irritated dogs and were a frightful nuisance to everybody.”

The motorcar needed champions. In America it was President Taft. In Italy it was King Victor Emmanuel III (1869–1947); and in Spain it was King Alfonso VIII (1886–1941) which brings us to this book.

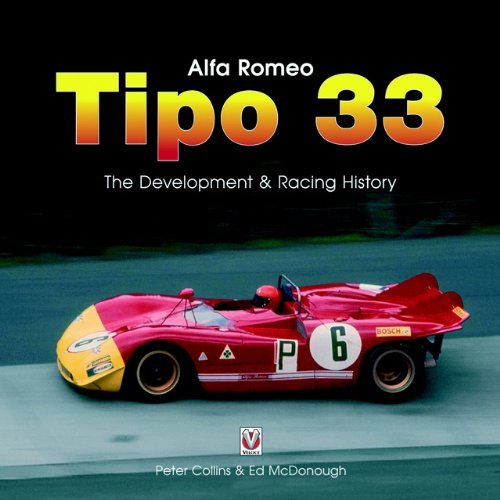

This out of print book serves as a general reminder that there’s a whole world out there beyond what is recorded in English. Perhaps the best example of that in this book is the clarification of which Duesenberg the king actually owned—details that have eluded enthusiasts for years. The actual details of the car are found in the book’s Appendix; it shows King Alfonso’s Duesenberg was recorded in his 1930 inventory of automobiles acquired as: “DUESENBERG 33 HP. 8 cilindros tipo J. Descapotable. N° chasis 2.303. N° motor J.282.” The Appendix goes on to similarly document another 96 cars acquired between 1904 and 1930. The book also shows a couple of rare pictures of the Duesie as well as the one that is regularly seen of him standing next to the car.

The author covers the arc of the subject in twelve chapters starting with the new king’s ascent to the throne and the arrival of the automobile in Spain, the king in his time and his automotive life, ending with the fall of the monarchy and his remaining years in exile. Naturally, it helps to be able to read Spanish, but the book is so richly illustrated that it’s a pleasure to peruse the pages and take in an early motoring perspective and history captured in the illustrations and pictures of the day. Surely the appendix listing of the king’s cars transcends any language barrier; and it is a delightful nugget to have survived (guessing, of course, that it was originated from an intact reference—but it could have also been a painfully researched amalgamation; the author doesn’t elaborate about the sourcing, and there is no index or bibliography to help clarify that point). The book does appear from time to time in Amazon searches (or other such sites), but commands a premium price reflecting the rarity of that occasional appearance.

Copyright 2017, Rubén Verdés (speedreaders.info).

This review appears courtesy of the SAH in whose Journal 285 it was first printed in substantially similar form.

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter