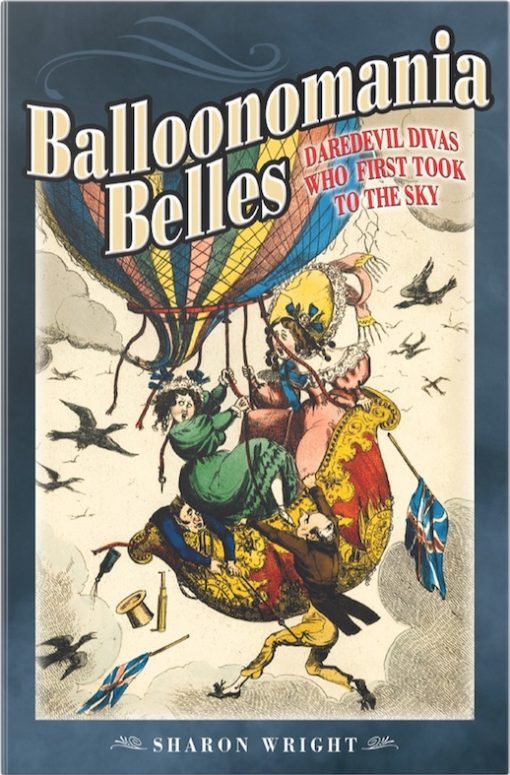

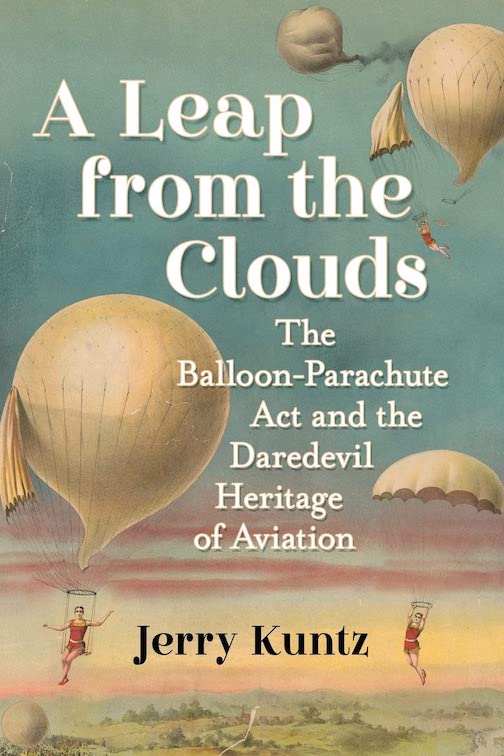

Balloonomania Belles: Daredevil Divas Who First Took to the Sky

by Sharon Wright

by Sharon Wright

“Stars of the stage where peculiarly suited to being the first women aloft. They were professionals, with the ability to master their nerves and perform under pressure. They were also glamorous and enjoyed attention . . . Aside from their professional skills, they had a measure of social approval for such a public role (though then, as now, people loved to speculate on celebrity sex lives).”

Sounds plausible enough, although, no matter how hard you shake this book, not all the puzzle pieces fall into place.

There is a quote halfway through, in a totally different context but that sort of applies to the whole book: “If the [Aeronautical] Society was for scientists, the [Aero] Club was for thrill seekers.” This book is more one than the other, which is not meant as qualitative verdict. What you get out of this book will very much depend on where on the spectrum from tabloid to scientific journal you fall. This book is fun and lively—an uplifting treatment of an uplifting subject—but if you are the sort of reader who, upon being told early on in the book (p. 33) that “iron to use in the manufacture of hydrogen” had suddenly become “a scarce commodity” then wonders what exactly iron has to do with anything (read up on Lavoisier, “steam–iron reaction”) or why it was scarce, you won’t find answers here.

Two other examples of brevity impeding clarity: how does someone in the space of two sentences go from having “earned a fortune” in ballooning to “owing a fortune” without any explanation (p. 55)? Or, from the same case study (p. 53), how does a “shy country girl [of 16] . . . small and nervy, and frightened by loud noises” even come to the attention of a 40-year-old balloonist who marries her because “she shared his devotion to ballooning”? It’s all possible—it’s just not laid out here.

Wright is an award-winning journalist and playwright, and she has certainly read the right books and talked to the right people to cover this subject, so it must be a deliberate choice to keep the book at only a certain level of magnification.

To put the modern-day reader into a 1780’s frame of mind, Wright points out that the Age of Reason was also the time when “the law made women the property of their fathers and then of their husbands” and the clergy postulated that balloons were “the devil’s horse.” Nevertheless, ballooning captured the public’s imagination right from the start—“Balloonomania” is an actual word, as is “balloon influenza” because of its infectious spread—a crowd of 400,000 attended the first manned ascent and only a year later the first woman went up. Wright presents several of the French, British, and American balloonistas; their origin stories vary and certainly the breadth of their careers (some died); what they have in common is that they are “the forgotten heroes of early flight.” The book will make you shake your head in wonderment and in pity and often enough in hilarity. That the idea of the Mile High Club should date this far back probably ticks all three boxes.

The book has an Index of people and places but it is fairly spare (cf. Charles Rolls, latterly of Rolls-Royce, was among the earliest aeronauts but is not in it although he is mentioned in the text). Eight pages of b/w images are bundled in the center of the book. They are in chronological order so the fact that only a few give any dates is not too much of an impediment; the earliest photo must be around 1880 so that alone is a remarkable thing to see. Speaking of dates, the text too uses them only sparingly so you often have to reread entire paragraphs to extrapolate what span of years a particular part of the story occupies.

So, we return to the earlier statement: if a breezy overview is what you want, with plenty of anecdotes and quotes in ornate Georgian/Victorian/Edwardian prose, this book is just the ticket.

Copyright 2019 (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter