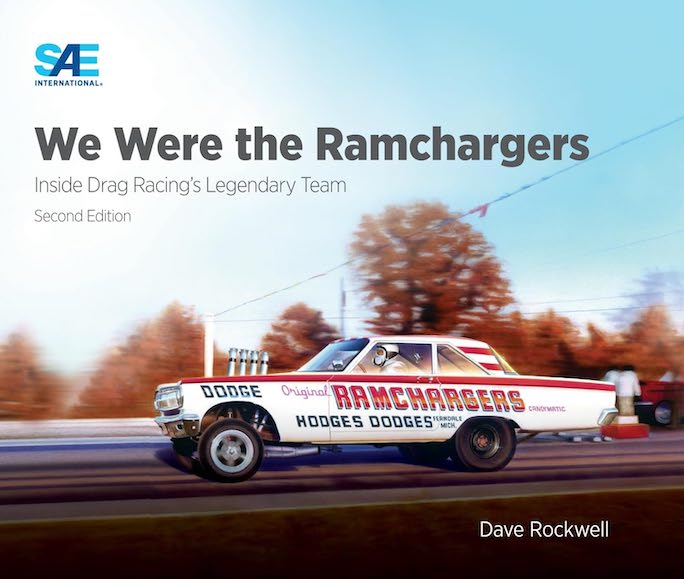

The Automotive Gray Market, An Inside History

by John B. Hege

by John B. Hege

Depending upon your age, you may have a first-person recollection of the gray market importation of cars into America that began with a trickle of vehicles considered exotics during the latter part of the 1970s. That trickle, numbering in the hundreds, became a flood in the tens of thousands toward its mid-1980s acme of 60,000! If you didn’t experience it directly, it’s a topic, as are the cars involved, that those who are automotively aware have at least heard about.

With this book, you can now read of and understand details not heretofore made really clear of the cars, the shops, as well as the entire backstory of The Automotive Gray Market. Author John Hege worked in conversion shops during the peak grey market era. As he phrases it, it “taught [me] a lifetime’s worth of lessons about people, money, corruption, government, and incidentally about automobiles.” He shares those perspectives in his clearly written first-hand account. It’s readable and enlightening although you will gain more if, as you read, you have your thinking cap tied on. That way you won’t miss the nuances of all Hege has to say for he doesn’t “write down” but rather expects his readers to understand terms such as stoichiometry.

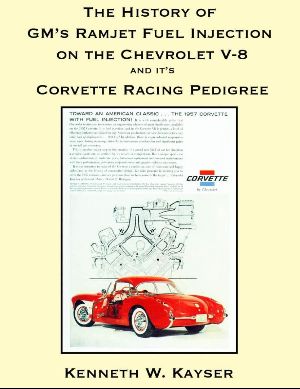

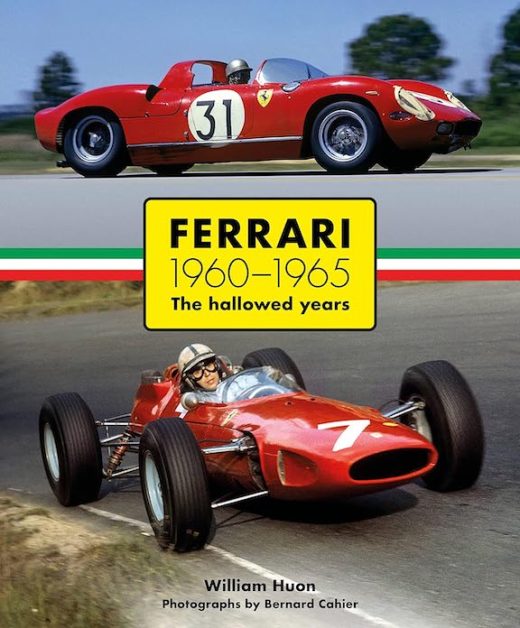

Examples of some of the cars which their manufacturers never intended to offer in the US, due to the expenses involved making them compliant, include late ‘60s Ferraris especially GTB 4s, late ‘70s Lamborghini Countach, 4- and 8-cylinder Morgans. As the 1980s dawned and foreign manufacturers were still slow to modify and certify cars to sell in the US, the number of gray market cars—particularly BMW’s 6-cylinder 328s and 725Turbos and Mercedes-Benz’s W123, 126 and 500SEL—increased practically overnight. They quickly overwhelmed the insufficiently staffed three governmental agencies—DOT/NHTSA, EPA, and customs—all of which individually had to approve the paperwork for each car, one by one.

The unauthorized importers and conversion shops bypassed factory channels because factory-supplied parts were too costly. They creatively retrofitted cars to meet US regulations and emission standards, at least theoretically. Even travel magazines got in on the act running story after story with teases like: “Take a trip to Europe and buy a car. Buy the right car and ‘even after paying the cost of shipping and compliance work, [you’ll] save thousands of dollars over the dealer’s price for the same car’ and essentially also pay for your trip from the profits if you then sell the car.”

You’ll meet an innovative and able cadre of people involved in gray market retrofitting as you read. So what brought the gray market to a screeching halt? What changed from the time when “anybody with enough loose cash to buy a car could buy . . . ship it home, contract the conversion and sell the car to an eager buyer. . .”? The oversimplified answer is those global finance realities often referred to as exchange rates. Not to mention, various European car makers were finally stepping up to making factory-built US versions of their desired models.

In his book’s concluding chapter, “Lessons of the Gray Market”, Hege shares his reasoned, long-view of the ramifications of the complex relationship between government and free-market industry. He writes, “Americans have always had a love-hat relationship with their government and healthy discourse requires that it always be that way. . . What the experience of the gray market should teach us is how agencies like the EPA or the DOT, or just as importantly NRC or the FAA, can easily be overwhelmed and become paper tigers when they are treated like political footballs, taken for granted and not properly funded. . . If something requires inspection, there must be inspectors to do the inspecting. . . Because if no one is there to do the oversight, a free market will call your bluff every time.”

Copyright 2022 Helen V Hutchings, SAH (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter