Bugatti: The Italian Decade

by Gautam Sen

by Gautam Sen

“Attempts at relaunching famous brands, such as Duesenberg, Invicta, Mercer, Stutz, and several others, had been made by many moneyed adventurers, yet all the projects, almost without fail, had ended in sorrow. So, in what way could Bugatti be any different?”

If you know your Bugattis you don’t even need the subtitle to spell out which model this book will be about, although there is a clue right at the bottom of the front cover photo.

It was no April Fool’s joke when on 1 April 1986 Messier-Hispano-Bugatti (SA), who owned the Bugatti trademark, faxed a contract to the fellows who, brimming with enthusiasm, had hatched the idea to resurrect the long dormant (for cars that is) and formerly glorious nameplate to build the world’s best, fastest and, heck, most expensive supercar, an idea that had sort of shaped itself into existence over a bottle or three of vino. We are in Italy and the wine is Sangue de Miura which sounds like it should have something to do with Lamborghini because it does, and it is Ferruccio L. who wonders if the slow life in his vineyard is worth giving up for one more big splash in the supercar world. Thus begins Bugatti’s Italian decade. It won’t even last the full span and end in bankruptcy, their dream car staying in production barely five years, with a total output that doesn’t even reach their one-year forecast.

A central figure in the EB110 story is Frenchman Jean-Marc Borel; many of his photos are used here. It simply boggles the mind that it was him, as a young student looking for ways to improve his Maserati-engined Citroën SM who would go visit the Maserati factory and while waiting for his appointment stop by his dream automaker, Lamborghini, then decide to write a book about that marque (he did two, in 1982 and another in ’85), which resulted in a friendship with Ferruccio L. and that fateful “What if . . . what if we were to build a supercar for today??” question. Later, it was him who was tasked with finding out if the Bugatti trademark was even available and making first contact, and he would become the Bugatti archivist which is how Sen gained access to so much original material.

The cast of characters that is involved at this stage, and will get involved subsequently, will be familiar to anyone with even a passing acquaintance with automotive engineering, design, and business matters. In other words, regardless of the degree of your interest in Bugatti, this book should be thought of as foundational. That six degrees of separation-aspect is also why author Gautam Sen is an ideal person to be in the driver’s seat for a story of such operatic sweep as this one. Read it alongside the books he has put forth in recent years and find yourself exposed to ever more layers of the “French and Italian automotive extravaganzas” that inspire him to shoulder the burden of deep research. There is a reason for this remark . . . consulting—and comparing!—primary sources is a key line of inquiry to the historian. The man who bankrolled and then presided over Bugatti Automobili S.p.A., Romano Artioli (b. 1932), would have been a prime candidate but he declined—because he, then 86 years old, was writing his own book, to be released in Bugatti’s 110th anniversary year, 2019 [1]. He did do that and gave it an excellent title, La costruzione di un sogno—Building a Dream, and its 220-odd pages turned out to not be the definitive word. Sen calls it “just one version of the story,” which is diplomatic; it is not even included in the Bibliography [2].

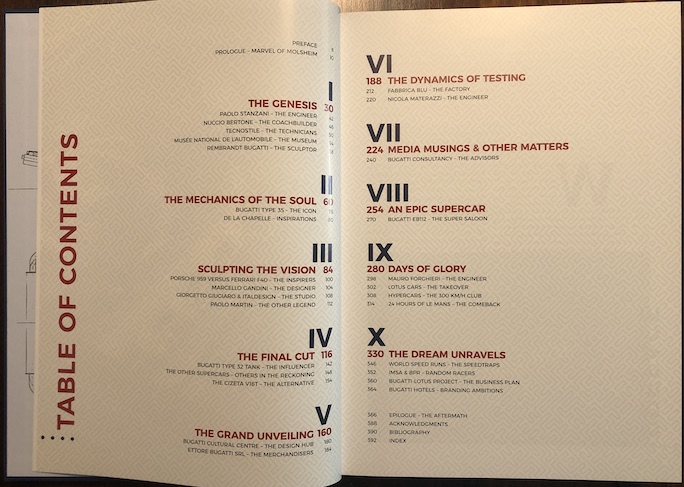

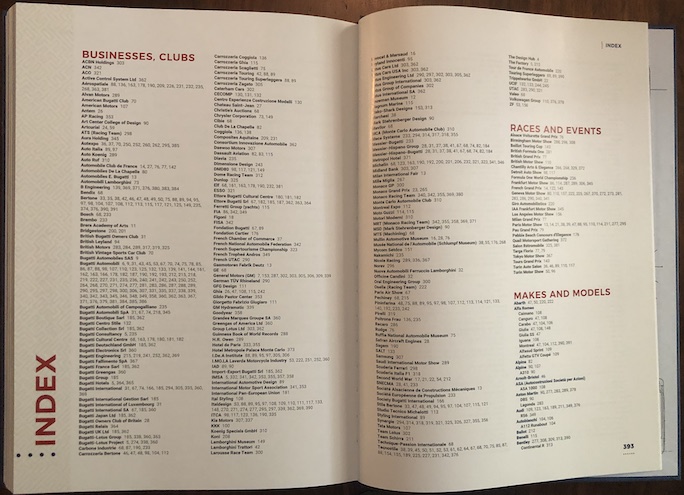

This is where a book stands and falls. A book without an index is . . . useless. Its absence can hide any number of snafus because you simply have no way of knowing what the book’s building blocks are. Presuming you know at least something about the subject matter, make the index your first stop. You can see that this one is subdivided into different categories; clearly this author expects the reader to bring independent thought to the table and is not afraid of leaving a trail of breadcrumbs to follow.

Around here we pride ourselves in wringing out a book forwards and backwards. No skimming the dust jacket blurbs and calling it a “review” or wasting words on retelling its story instead of analyzing its methodology and merits. This is a long-winded way of saying that this is a supremely thorough book that not only moves the goalposts farther forward but also proffers reasons for reevaluating certain aspects of the delivered canon, to name just two: the school/s Ettore’s father Carlo had attended, Jean Bugatti’s role at the family firm. These items are peripheral to the EB110 story and we mention them only to substantiate that Sen drills deep which, in turn, means you are in good hands. His is the book you will be wearing out from consulting it for years to come; at present; there is no other book that casts as wide a net—from all aspects of the car’s genesis and life cycle to model cars and merch (profits of which were forecast to exceed that of the cars!), EB110 prequels/sequels as well as continuation cars and the competition, the totally over the top factory, how Lotus factored into Artioli’s calculus, and, not least, the folly of overreach which takes us back to the opening quote.

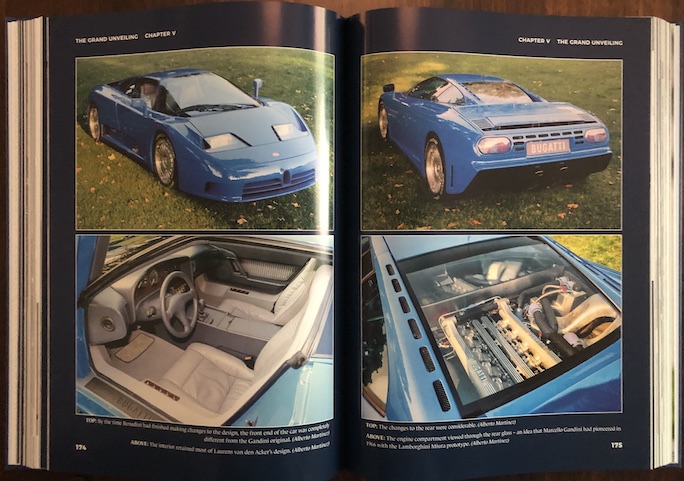

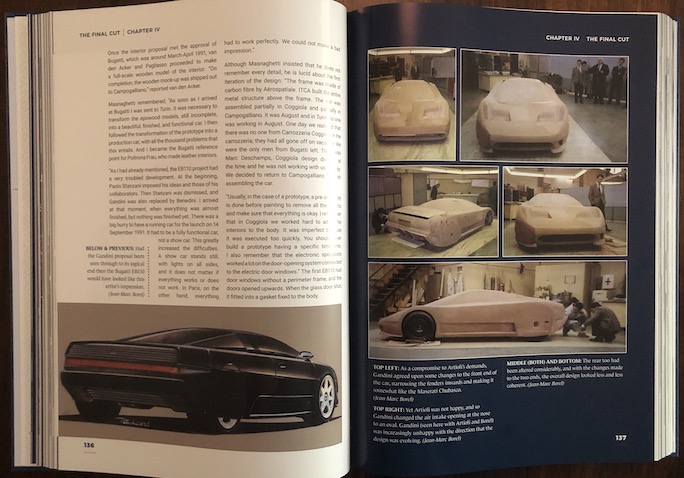

That the EB110 would be built in Italy has nothing to do with Ettore Bugatti’s Italian origins. As built, it does not look particularly French or Italian but in the rejected Gandini proposal shown here the car definitely has a French flavor.

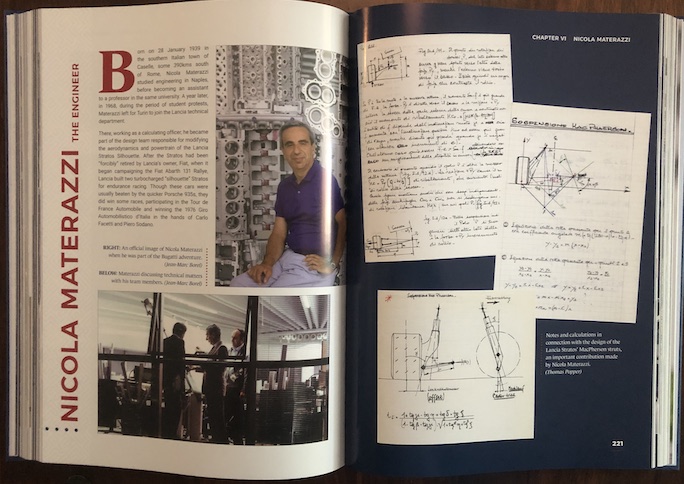

The handwritten pages on the right are not the EB110—we show this page simply to illustrate that the brain trust working on the car came from all corners of the industry, which is a different way of saying that readers with all sorts of interests will find something in this book that connects to something in their specialist niches.

Savor the book, it is rich both in the specific context of the EB110 and in the wider sense of showcasing what makes a book a good book, which also extends to the ancillary aspects of a fine book such as Dalton Watson’s designer’s always sure hand. Many skills can be learned or emulated, but writing/research . . . ? However he came by it, Sen has a knack for doing this sort of work. Good thing he’s energetic enough to have more books in him! The next one is already in production but a bit of an outlier, Alfa Romeo SZ Coda Tronca: The Art of Conservation by Corrado Lopresto and coauthored with Sen and Paolo Di Taranto.

The EB110 was no high-strung cream puff—anyone could drive it every day, everywhere. Well, if you had no baggage bigger than what would fit into the glove box.

- Not to be confused with the 110th anniversary of Ettore Bugatti’s birth (1881) which is how the EB110 got its name. And doesn’t “one-ten” sound better than “one-oh-nine” which is what the car would have had to be called if the prototype that had been kept under wraps at the factory’s inauguration in 1990 would have been unveiled then? Speaking of names, did you realize that the new company was almost called “Fiorita Duemila” or “Ferrucio”? Or that Artioli really wanted to dust off the Isotta Fraschini nameplate?

- The Italian version appeared in 2019 as a hardcover titled Bugatti & Lotus Thriller, La costruzione di un sogno with a foreword by Vittorio Feltri (Cairo Editore, ISBN 9788830900172), followed by an English version in 2020 with a foreword by TV personality and car collector Jay Leno (published by Artioli, ISBN 9782957150106). Both are easily found, and under 20 Euros.

Copyright 2023, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter