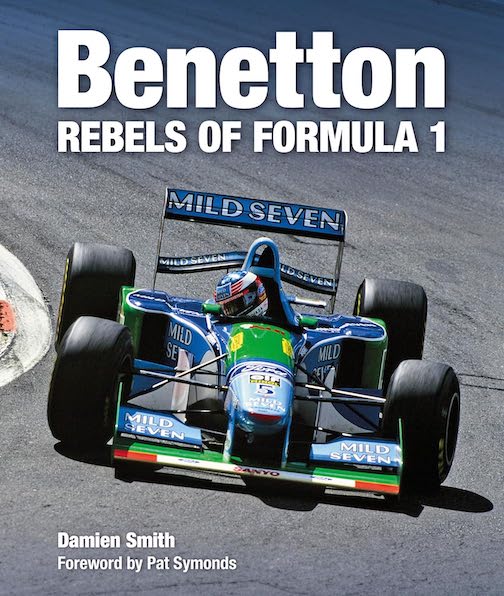

Benetton: Rebels of Formula 1

by Damien Smith

by Damien Smith

Foreword by Pat Symonds

“Today, all we can do is take the Benetton players of 1994 at their word and state what we know. But only they can look themselves in the mirror and face whether their truth is the same as the whole truth.”

The Alpine Formula 1 team started life as Toleman in 1980 before becoming Benetton, and then Renault, Lotus, Renault again, and it is currently Alpine. For now.

No wonder it’s often called Team Enstone, after the Oxfordshire village that became its base in 1991. Fernando Alonso won back-to-back titles with Renault in 2005/06 but, in hindsight, these seem almost formalities, untainted by serious protest or controversy. And what a contrast to the Benetton years that was . . .

Author Damien Smith is the British motorsport journalist who is ideally placed to write the Benetton story, having been immersed in the sport for almost thirty years. As one time editor of Motor Sport, and editor in chief of F1 Racing, Autosport and Motorsport News, I’ve no doubt the author’s contact book is a Who’s Who of motor racing. It needs to be, because the story of how a trendy Italian knitwear company became a dominant force in Formula 1 is fiendishly complex. It featured Machiavellian plotting, spawned conspiracy theories aplenty and repeated accusations of cheating as the team went on to achieve huge success. The price paid was that Flavio Briatore and Michael Schumacher shared equal billing as cartoonish rogues, with a supporting cast of self-proclaimed disrupters, set to a backing track of loud rock music from the pit garage. Oh my, what larks these boys and girls had—as they never tired of reminding everyone.

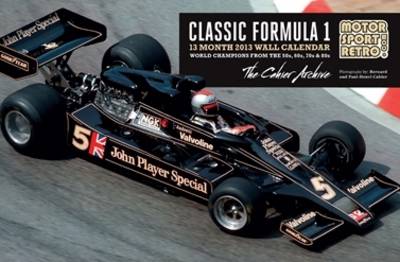

Schumacher and the gathering storm. Benetton B193 at Estoril 1993.

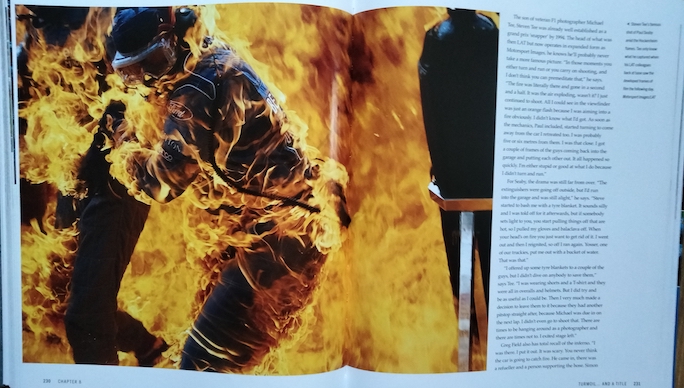

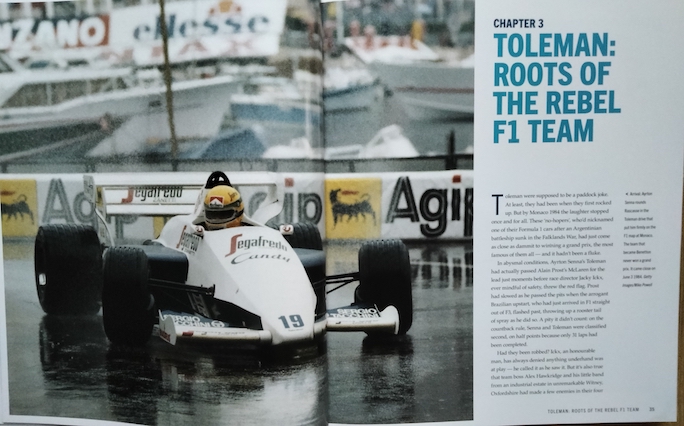

Evro Publishing has done full justice to the Benetton saga with this 344-page heavyweight hardback, with Smith’s forensically researched prose leavened by almost 300 illustrations, including the famous picture of mechanic Paul Seaby engulfed in flames at Hockenheim. And the book doesn’t confine itself to Benetton the eponymous team, but also describes its origin in Toleman. In fact, there’s a full chapter about Toleman, describing its ascent from special saloons to Formulae Ford 1600 and 2000, then success in Formula 2 leading to its Formula 1 debut in 1981. As the author puts it, “Toleman’s support of motor sport was a broad church.”

Burning Man. Paul Seaby engulfed by the pit fire, Hockenheim 1994.

Toleman ploughed its own furrow, being dismissed by many as its struggled with its Brian Hart-powered turbo-engined car, crassly nicknamed the General Belgrano (after the Argentinian warship, sunk with huge loss of life in the Falklands War). But this minnow of a race team soon started swimming with the piranhas, pulled the coup of signing Ayrton Senna for the 1984 season and nearly won the soaked Monaco Grand Prix, albeit with Tyrrell’s wunderkind Stefan Bellof in hot pursuit. And it was Tyrrell, of course, which had first sported the distinctive Benetton polpetto logo as it took its final Grand Prix victory the previous year at Detroit.

Ayrton Senna in the 1984 Monaco Grand Prix, Toleman TG-184 Hart.

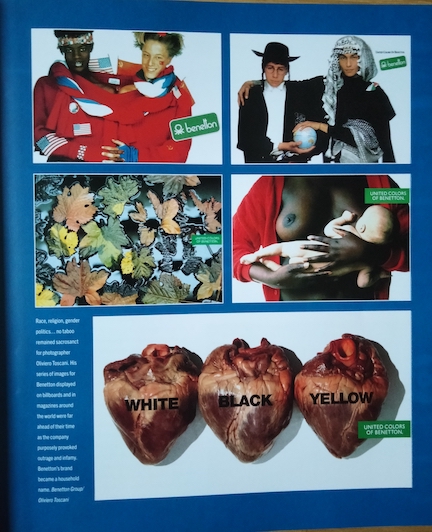

A selection of the controversial Benetton advertising—race, religion, and politics.

In the 1980s Benetton’s bold branding and provocative advertising had made knitwear sexy and Damien Smith rightly devotes space to describe the impact the Italian firm made in a decade notorious for its excesses. The reproduction of period advertisements reminds the reader how “Race, religion, gender politics . . . no taboo remained sacrosanct for photographer Oliviero Toscani.” Further insight is obtained from the Epilogue, an interview with Alessandro Benetton conducted by the author in January 2023, and accompanied by pictures of the family collection of Formula 1 cars and “the beautiful Villa Minelli Benetton HQ.” Only an Italian firm’s HQ could look so achingly gorgeous!

The chapters on the ascent of Benetton from sponsor to a pukka Formula 1 team are absorbing, not least because the author focuses on the commercial as well as the technical. I agree with the author that the template for today’s all- conquering Red Bull team was evident in Benetton’s self- proclaimed iconoclasm thirty years earlier. The DNA of the Austrian firm’s “Energy Station” clearly evolved from Benetton’s marketing and hospitality innovation, back in the pre-Schumacher era of Berger, Boutsen, and Nannini. Team stalwart Pat Symonds mentions “. . . the different marketing vibe . . . Benetton employed Patrizia Spinelli, whose job was to get the teams into lifestyle magazines . . . we had high profile guests at races in the days when that wasn’t really done.” Perhaps no driver epitomized the early Benetton style more than Siena’s Alessandro Nannini, about whom Symonds said, “Very talented, very natural, never did any work, never spent time thinking about the car, did as little exercise as he could get away with.” His career was cut short by a helicopter accident, and I struggle to think of a spiritual successor in a sport that now takes itself so seriously.

Damien Smith devotes 50 pages to the chapter entitled “Turmoil . . . and a Title”, which describes the momentous triumphs and tragedies of the 1994 season. As Niki Lauda famously had put it, “For ten years God had had His hand on Formula One, and then he took it off.” Ayrton Senna died at Imola, trying to keep ahead of Michael Schumacher, whom Briatore and Walkinshaw had signed (under Eddie Jordan’s nose) in 1991. Schumacher’s self-belief and win-at-all-costs attitude, as well as his undoubted talent, made him the perfect fit for a team consumed by ambition. The author’s access to so many Benetton alumni has enabled him to provide a detailed account of the season that changed Formula 1, arguably like no other. It is an objective account, but for this reader it awakened memories of the team that appeared to have sold its soul for the success it craved. Controversy goes hand in hand with success in motor sport, but the author reminds us just what an orgy of accusation and intrigue the Benetton team triggered in 1994. Let me count the ways—there was the “option 13” traction control software (disabled, or so they said), Schumacher’s black flag myopia at Silverstone, the refuelling irregularities at the heart of the Hockenheim inferno, and the suspiciously worn plank at Spa. But there had been no doubt that, by 1994, Benetton was ready to join the Formula 1 elite; after recruiting and then firing the abrasive genius, John Barnard, Benetton achieved its peak success by deploying the technical firepower of Messrs Brawn, Byrne, and Symonds (inter alios) and the entrepreneurial elan of Flavio Briatore, the perma-tanned rogue who epitomized Eurotrash chic. The Adelaide Grand Prix in 1994 was both apogee and nadir—Michael Schumacher, seemingly untroubled by ethics or conscience, won the world championship by deliberately crashing into Damon Hill, who had been set to win for Williams. Now consider the words of Joan Villadelprat, Benetton’s almost comically alpha male team manager: “That was funny the way it finished . . . As soon as it happened I went straight to the stewards, shouting the fault was Damon’s.” That was funny? I must have missed Frank Williams, Patrick Head, and Damon Hill enjoying a carefree chuckle. The author’s verdict on the 1994 season is hard to contradict: “One of the most traumatic, controversial and deeply troubled seasons was finally over, and in that context perhaps it got the ending it deserved, even if Hill didn’t.”

There was more success for Benetton but less controversy in 1995, and as for the next year, in a nod to Neil Young the chapter subheading says it all, “1996: After the Goldrush.” Benetton was to soldier on until the Japanese Grand Prix in October 2001 and, although the author describes the team’s erratic descent from summit to foothills (“The Slow Spiral Down”) with the same diligence as characterizes the rest of the book, it feels almost parenthetical.

The team from Enstone now identifies itself as Alpine but I dare say it will sail under whatever flag is more convenient in future for this team of guns for hire. 2009 was the year of “Crashgate”—when running the works Renault team Messrs Briatore and Symonds were found guilty of conspiring to win the 2008 Singapore Grand Prix by having coerced Nelson Piquet deliberately to crash. This grubby tactic enabled Fernando Alonso to employ an apparently bizarre pit stop strategy that almost guaranteed victory. But this time they didn’t get away with it. The former Benetton guys might have been wearing Renault-branded shirts in 2008 but, what was it Shakespeare said? “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet”? Some rose, and some stink. And Singapore helped answer the question posed in Jeremiah 13:23: “can the . . . leopard change its spots?” By this time the triumvirate of Benetton emigres (Brawn, Byrne, Schumacher) had enabled the German driver to win 72 Grands Prix for the Maranello team, largely unmired by scandal.

This really is a terrific book and it is testament to its quality that I have allowed more of my own views to color this review than I really should have done. But my reaction was only reflective of what Benetton wanted to achieve in the first place—disruption, controversy, and acres of publicity. And who cared whether it was good or bad?

2023 has been a very good year for motorsport books and Benetton – Rebels of Formula 1 joins Richard Jenkins’ Tyrrell – The Story of the Tyrrell Racing Organisation, James Page’s Superbears – The Story of Hesketh Racing, and Crispian Besley’s Driven to Crime – True Stories of Wrongdoing in Motor Racing as candidate for motorsport book of the year.

Copyright John Aston, 2023 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter