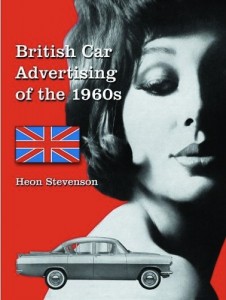

British Car Advertising of the 1960s

by Heon Stevenson

by Heon Stevenson

The run from Land’s End in Cornwall to John O’Groats in the north of Scotland is the longest distance in the British Isles. At 874 miles it is approximately the distance from one end of Texas to the other. No wonder that for years the British, and the rest of Europe for that matter, have had a hard time comprehending America’s wide open spaces. Their misperception of the space we occupy has, albeit indirectly, influenced the advertising that is the subject of Stevenson’s book.

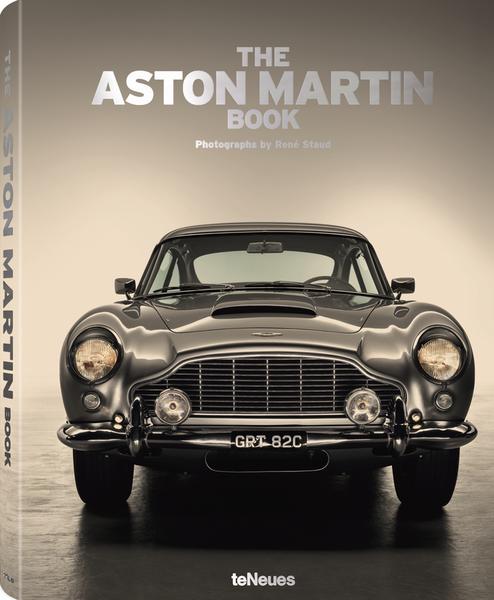

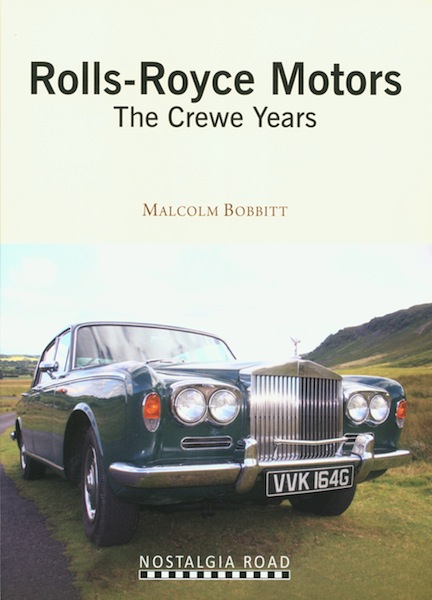

The British have built memorable cars since the turn of the last century—for many years at the luxury end of the market. In this island nation distances were simply not as great as in the US, and till well after World War II public transportation was cheaper, faster and worked just fine, thank you very much. British motoring was a sport, and the country discovered the automobile as a “transportation appliance” only well after Americans did. Austin Sevens notwithstanding, one simply did not need a car to get from here to there in prewar England. Stevenson in his introduction notes that “During the 1960s the automobile finally secured its position as an indispensable component of daily life in Britain”—a transition that began in the United States fifty years earlier with the introduction of the Model T Ford.

If the 1960s were a critical automotive decade in Great Britain (car ownership more than doubled during this decade), Stevenson does much more here than simply reprint a series of car advertisements. It should be noted that he has written extensively on advertising and automotive history and is an SAH member as well as a Friend of the History of Advertising Trust. Eighty of the book’s 429 pages are devoted to a dozen Appendices and Notes that provide valuable reference material. Among other things he includes “year letter suffixes” for British license plates, production and registration figures, import and export statistics, a list of leading car advertisers and how they apportioned their ad dollars, car advertising agencies, ad expenditures by marque, and a great deal more—including a comprehensive Index that should warm the heart of advertising fans everywhere.

Subdivided into family, luxury/sporting and import [to the UK] models, marques are described in alpha order within each section. The text aims to present the cars in the context of society as a whole and the aspirations, lifestyles, and economies of its various strata. It also delineates the various carmakers’ philosophies and how they read “their” respective markets, which, in turn, informed their advertising decisions.

American advertising in the 1960s marked the beginning of what is now called the “creative revolution.” Doyle Dane Bernbach, Papert Koenig Lois, Freeman & Gossage, and Carl Ally were creating startling new advertising for VW, Peugeot, Volvo, and Range Rover. And while Britain’s popular culture was swept with hipsterism at the same time—Twiggy, Mary Quant, the Beatles—British car advertising remained, well, British, and shows no sign that the advertising revolution crossed the pond.

Stevenson has included 188 illustrations (8 in color) in this volume whereas his book on American automotive advertising, which is only about half as long, contains 280 illustrations, of which 21 are in color. More illustrations in this book would have helped him better illustrate his case. But what is included does show a clear transition in ad style as conservative design and old-school graphics turn into—relatively—sleeker illustration and type treatments. But the styling of the cars themselves—at least to the eyes of an American observer—is dowdy and uninspired. Car enthusiasts looking for some deeper message from these advertisements will wonder whether they aren’t witnessing the beginning of the decline of the British motor trade.

One wishes Stevenson’s book had gone further, delving deeper into the context in which this advertising appeared. Still, this exhaustive work appears to be a unique look at an important advertising category and is worth the price of admission for that alone.

Copyright 2011, Arthur Einstein (speedreaders.info).

Reviewer Einstein is himself an ad man and has written a book about Packard advertising.

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter