American Automobile Advertising: An Illustrated History 1930–1980

by Heon Stevenson

by Heon Stevenson

American’s have a long-standing love/hate relationship with Madison Avenue. One minute the guy next door is complaining there’s way too much of it (there is) and he doesn’t pay any attention to it anyway. Then, almost without taking a breath he’s asking Dilbert in the next cubicle if he happened to see the latest Miller spot and how about those outfits the cheerleaders were wearing! Voting for the most popular Super Bowl ads has becomes a national pastime. Even commercials written by so-called amateurs (a.k.a. people who have different day jobs) are winning awards at advertising festivals.

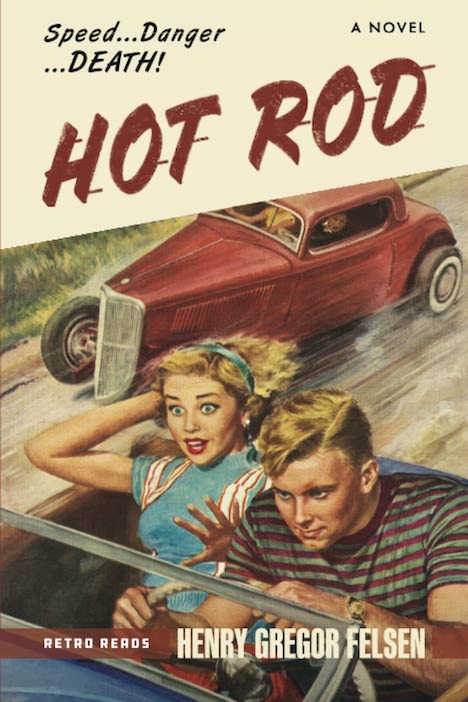

The center ring of the advertising circus is occupied by automobile advertising. Patent medicines occupied that spot for a while. Cigarettes threatened to take over. Beer and soft drinks have been contenders. But for the past century cars have been the stars—sexier, more expensive, and an obvious signpost on the road to affluence. Never mind that they got off to an uncertain start back in the early days when car ads appeared mostly in motoring journals. But by 1910 the advertising business was hitting its stride. Advertising in magazines and newspapers helped shape opinion. Ads made writers, artists, and photographers famous. By 2000, when Advertising Age picked the 100 best ad campaigns of the 20th Century, eight of them came from car companies and two from car rental firms.

It’s obvious, then, why Stevenson (a Brit who has written extensively on autos and ads) has chosen to follow his book on British car ads with one examining American automobile advertising. The level of magnification of each book is rather different, as is their respective scope. In choosing to here cover six decades—1930 to 1980—he has probably bitten off too large a chunk of automotive history, and it is rendered only partly digestible. Still, Stevenson should get high marks for attacking the subject at all. The sheer act of collecting so much interesting material can’t be taken lightly. Especially when he has taken the trouble to explore some of the side canyons of the car ad world—where else would you be likely to find reproductions of the “Love Letters to Rambler” campaign, inspired by American Motors president George Romney?

The author has provided useful chapter notes and a comprehensive index that will let curious readers mosey through the book in their own time and in their own way. He divides his work into three parts (Part One: Fueling the Fantasy, Part Two: Beyond Mechanism, and Part Three: Reality Supervenes), but these divisions seem arbitrary and not connected to the work itself. It contains 282 reprints of advertisements, 21 of them in color. The advertisements, as noted above, are reason enough to buy this book—in spite of the fact that the text that accompanies them is sometimes baffling.

The bafflement stems in part from what is not included and in part from what is. What some readers will miss are names. Very few of the agencies that created the work are listed (unlike in his volume on British car ads). The writers, artists, art directors, advertising managers, and the others who slaved to get these ads approved and into print are thus lost to history, or at least to the reader. It’s no easy task to find them of course, but many can be found, and history without actors is missing an essential ingredient. One is inclined to attribute this lack of detail to Stevenson simply not being as familiar with the US advertising landscape as he is/was with the British—and tackling more than half a century worth of advertising as opposed to a mere decade in his other book.

Stevenson spends much of his text commenting on advertising technique. There is “sober, intellectual copy from N W Ayer.” He finds that Buick “anticipated the hyperbole and fanciful copy of later years in 1938.” And, “By the mid-1960s, the male benefactor was in retreat as more women chose their own cars and enjoyed a measure of autonomy”—a retreat that was set in motion by many advertisers before the first World War in the pages of Cosmopolitan, The Woman’s Home Companion, The Saturday Evening Post and others.

The transition from print to radio and television, which by 1960 had become major media outlets for automotive advertisers, is missing entirely from the picture Stevenson paints. And his often overheated assessments of cars, companies, and their advertising will strike an off note with some, e.g. “. . . the Corvair was a controversial freak that only a highly skilled driver could handle at speed . . .”

Books about automobiles abound. Books about automobile advertising are all too rare. The comprehensive advertising collection in this book is indeed worth studying but the author’s commentary, while often hitting the mark, too many times wanders off in no discernable direction. If you know his British book, reset your expectations.

Copyright 2011, Arthur Einstein (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter