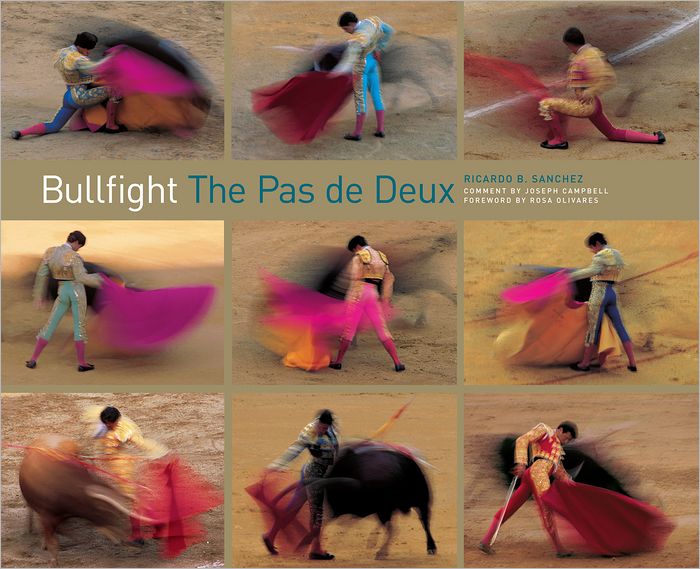

Bullfight: The Pas de Deux

by Ricardo B. Sanchez

This book is about art, photography, things unseen, thoughts unthought, managing fear, and, oh, bulls.

Imagine this book had one of those sound chips that are embedded in greeting cards to blare silly pronouncements or play little ditties. If this book opened to a rousing rendition by a Banda Taurina you’d be out of your seat right away. But, it doesn’t need such gimmicks to get your attention—IF you have an open mind. This book is simple only on the surface—very much like its topic. It’s easy to have an opinion about bullfighting, although it’s probably more a culturally conditioned knee-jerk reflex than a reasoned response.

“The bullfighter, in his solitary confrontation with the bull, seems always to ask this eternal question—what is it that happens or comes to pass in our lives, in death?”

Ernest Hemingway said, “There are only three sports: bullfighting, motor racing, and mountaineering; all the rest are merely games.” Those three have two things in common: inherent danger and uncertainty of outcome. Hemingway was so taken with the subject of the nature of fear and courage that he wrote a novel about the ceremony and traditions of Spanish bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon (1932). While death is a regrettable, extreme, and unwanted byproduct of danger and uncertainty in two of Hemingway’s sports, the third has the specific purpose of ending in the demise of one of the protagonists.

The “pas de deux” reference in the book title is less ponderous than it may at first seem, not only because this ballet term means “steps of two” (in this case the bull = male and the bullfighter = female) but also because the Frenchman who is credited with coining it in the 1850s—Marius Petipa, considered the most influential ballet master and choreographer that ever lived (Swan Lake, The Nutcracker, Sleeping Beauty etc.)—specifically had in mind the theatricality of highly stylized folkloric dances such as in the Spanish tradition. And once you remove the unpredictability of action/reaction from the bullfight it is nothing but stylized ritual.

Right in the first sentence of the Acknowledgments Venezuelan photographer Ricardo Sanchez calls it the “dance between light and shadow and life and death.” It is critically important that the reader not dismiss such language as mere fireworks or trite platitude. The book’s real purpose is to deal with Big Questions, not to show dashing men (there are female matadors, but not in this book) in silken purple socks and glitter suits stabbing pointy sticks into drooling animals. In that regard, a name listed right there on the book cover needs explaining: “Comment by Joseph Campbell.” This American mythologist certainly has a reputation for examining Big Questions but he died in 1987 so, obviously, he has nothing to say about this book. His “comment” consists of one single quote about the mythological connotations of the bullfight at the beginning of the book. A good quarter of the book consists of such quotes, each printed by itself on a verso page. To single out Campbell is a weak attempt at claiming intellectual heft by enlisting the halo effect of a marquee name—the book does not need this gimmick either, not least because of the other name on the cover: Rosa Olivares, who wrote a Foreword of great depth.

It is positively shocking that nothing is said about her, save for a small blurb on the book jacket flap. How can a reader know what relevance to attach to her words without knowing who she is? These days, she is director and editor of several magazines under the EXIT name. One is photography-driven and champions a visual discussion of today’s culture, another is dedicated to theory and contemporary art books, another to interviews and general goings-on in the global art scene. Beyond that she is a pillar of the contemporary art world and noted art critic and promoter. Thinking and communicating about art is her stock in trade and thus her Foreword here matters.

This book is all about the photos but don’t be in any hurry to get to them, lest you completely miss the point of the book. The Foreword is only 12 pages but if you read it right, it’ll take you hours to chase the meaning of its complex ideas. It is a bold piece of writing inasmuch as it is not afraid to attempt to seek words for that which resists being articulated. It centers on camera v reality. Try this sentence: “Light is the origin of color, the essence of painting, the basis of photography. And deceit converges in light. These photographs simply document deceit.”

More importantly, the photographs themselves deceive the viewer. Not in the sense of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle or the Observer Effect that says, paraphrased, the act of observation affects reality, but in the sense that what the photo shows is not what, or rather how, the matador sees. As Olivares says, “This knowledge may change our concept of what is real, making us doubt what we believe because we see it and what we do not believe because we cannot see or perceive it with our senses.” Think, for instance, how irreconcilable the reality captured by a high speed camera and shown in super slow motion is with what your own eyeballs see in “real time” (now there’s an expression that invites exploration!).

If you ponder the Foreword the way it needs to be pondered you’ll see why Sanchez treasures the “countless hours talking with [Olivares] about how seduction, deception, illusion and truth are fundamental to the way our society and culture function.” You would too if you had the opportunity to talk with someone like that. If the words in bold sound familiar, good for you. You either already have an interest in bullfighting or an exceptional memory. They are the words of the subtitle of a previous book Sanchez did, Passes: The Art of the Bullfight; Seduction, Deceptions, Illusion, and Truth (Rizzoli 2001, ISBN-13: 978-0847823673). On that book he was the photographer and the author was Jose Luis Ramon Carrion, a bullfighter turned journalist who wrote several books on the subject and is Editor-in-Chief of a bullfighting magazine. That book is not as cerebral as this one but, photographically, they are much alike. (So much for the book jacket of the new book touting it as “the most unique and elegant record” of the sport.)

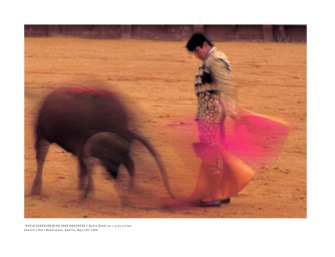

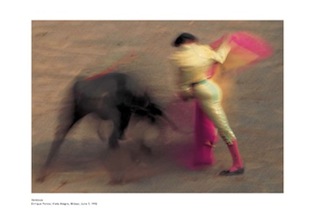

By this point in the review you may have all but forgotten about the photos! They capture motion. Ergo they are blurry. This is not a defect but how they tell their story! Looking at the photos without having read the commentary by Olivares and Sanchez is bound to frustrate! If you don’t like modern art by, say, a Mark Rothko or even a Picasso, these photos—artworks in their own right—may not resonate. The photos illustrate the repertoire of “recognized” passes (see cover) used in the three distinct phases of the fight Sanchez describes in his Introduction. Again, the dance/ritual analogy is borne out. There is one single, large photo per landscape (12.3 x 10.2˝) page. The caption states the name of the move (Véronica, Tafallera, Doblón, Estacada etc.), the matador, location, and date. Only 106 of the over 10,000 photos taken at 160 fights over the course of 10 years are shown here. Clever touch: the background colors on the pages with the quotes relate to the color palette of the photos.

Bullfighting terminology, procedures, and customs are explained, as are the bulls. While it is commendable that the book doesn’t try to read anything into the red color of the muleta, the novice reader should probably be reminded that the bull, being color blind, sees it as grey and is thus not provoked into “seeing red.” A closing page addresses film, speed, and why and when post-shoot color manipulation was considered necessary. There’s even an Index. “¡ole!”

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I’ll start by saying I do not buy Hemingway’s rather arrogant assertion that all sports but motor racing, mountaineering and bull fighting are mere games. First of all he ignores the obvious fact that they have two sides – spectators and participants. And what can be life-threatening for the participant is usually just an adrenaline rush for the spectator. I’m not enough of a philosopher to parse the difference between the risk a mountaineer takes as a participant when scaling K2 and the thrill a crowd of Spaniards gets watching an afternoon of barbarism in the bull ring – but there is a good deal to ponder there, as you say. Based on what I read and what I see in your review, I’d say this book is all about some spectacular photographs, any one of which I’d be thrilled to have blown up and hung in my house.

Ricardo B. Sanchez’s photographs are absolutely spellbinding. They more closely resemble paintings than photographs. The introduction and foreword give some background to the history and tradition behind this sport. I have long been intrigued by the Spanish tradition of bullfighting and this book is a gem!