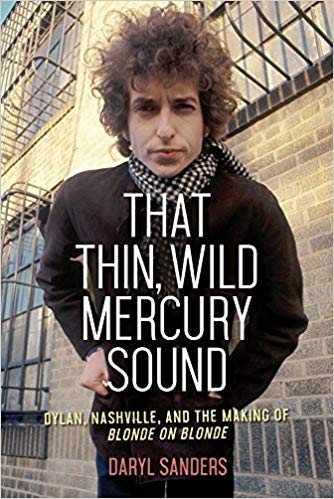

That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound

Dylan, Nashville, and The Making of Blonde On Blonde

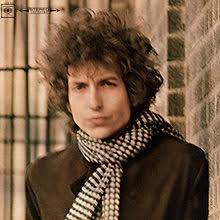

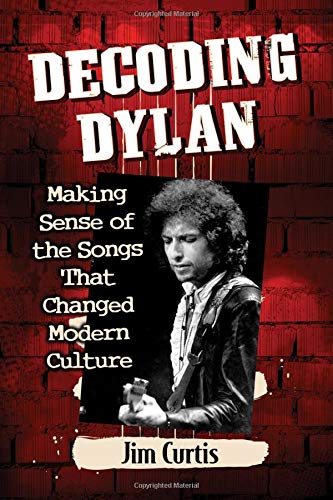

During the Summer of Love, Shadyside, a once elegant Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, neighborhood, became, in some respects, a little Haight-Ashbury. Lucky me—after living for some years in Small Town America, I attended school in Pittsburgh and roomed in Shadyside. Going into a record shop there, all vinyl then, of course, I saw for the first time Bob Dylan’s 1966 release, Blonde On Blonde. Except for the tiny font on the spine, there was no album title, song titles, or credits to be found on the cover. The obverse of the gatefold album wrapped around to the reverse to show a three-quarter photograph of Dylan taken on a bone-chilling day in the Meat Packing District of New York City.

The clerk wore calf-length boots and his dark hair passed his shoulder blades. I asked him if I could open the album. No can do. I had wanted to read the song titles. No need to break the seal. This young hip man rattled off all the song titles for me: “Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35,” “Pledging My Time,” “Visions of Johana” then all the way to “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” It wasn’t until a few weeks later, when I finally laid my money down, that I got to see the inside photos and credits.

My Shadyside room was a small box among other small boxes that had been carved out of a large bedroom of a once splendid mansion. Although my room there was tiny, I and others rooming there had access to a large living room, and I particularly liked whiling away my time on the window seat beneath the large stained glass window. Ah, the memories. And in my small room, on my tiny, low-fi record player, I played all four sides of Dylan’s opus. Over and over again. For many days in a row. Spellbinding. Far out. Rock’s first double album. Nothing quite like anything else at the time; and, yes, there was, for comparison, much fine and inventive music happening during these salad days: The Beatles, Cream, Jefferson Airplane, The Byrds—and others both well-known and obscure.

My Shadyside room was a small box among other small boxes that had been carved out of a large bedroom of a once splendid mansion. Although my room there was tiny, I and others rooming there had access to a large living room, and I particularly liked whiling away my time on the window seat beneath the large stained glass window. Ah, the memories. And in my small room, on my tiny, low-fi record player, I played all four sides of Dylan’s opus. Over and over again. For many days in a row. Spellbinding. Far out. Rock’s first double album. Nothing quite like anything else at the time; and, yes, there was, for comparison, much fine and inventive music happening during these salad days: The Beatles, Cream, Jefferson Airplane, The Byrds—and others both well-known and obscure.

That the cover photo was taken in the Meat Packing District on a cold afternoon (by Jerry Schatzberg) is one of the many, many details that Daryl Sanders offers in his book. There are twenty pages of notes giving evidence of his many interviews with those involved in the making of Blonde On Blonde, and the many articles, books and albums he used in his research. It is obvious that Sanders had spent many hours, probably weeks (months?) carefully listening to the 18 (!) disc set, the Collector’s Edition of Dylan’s The Bootleg Series, Volume 12: The Cutting Edge 1965–1966, the outtakes and other material from the Blonde On Blonde sessions. His dedication is admired and the results of such avidity make for the book’s amplitude and reliability.

“Nashville cats, been playin’ since they’s babies

Nashville cats, get work before they’re two….”

—John Sebastian (The Lovin’ Spoonful) *

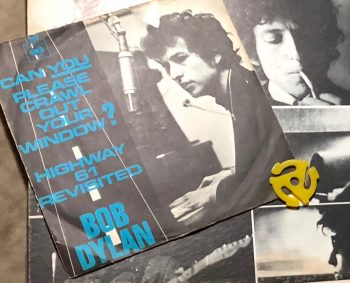

In New York, in January of 1966, with his new producer Bob Johnston, and with Al Kooper (The Blues Project, Blood Sweat and Tears), Robbie Robertson**(The Band) and a handful of session musicians, Dylan began recording what was to become this deft and groundbreaking album. Because of the clout and credibility he had commanded from the monster hit “Like A Rolling Stone,” unlimited studio time was taken for granted by Columbia Records. Sanders relates many of the false starts, dozens of different takes, breakdowns, experiments and downtime.  Although the non-album single “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” was released before Blonde On Blonde, only one song from these sessions made it to the album itself. Johnston had wanted to take Dylan to record in Columbia Records’ Nashville studio. And he did.

Although the non-album single “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” was released before Blonde On Blonde, only one song from these sessions made it to the album itself. Johnston had wanted to take Dylan to record in Columbia Records’ Nashville studio. And he did.

By the mid-sixties, Nashville was known for the A-Team, a group of young, talented, hard-working session musicians. Charlie McCoy, Wayne Moss, Hargus Robbins, Kenneth Buttery and the rest of the crew were known to cut records efficiently and with consummate skill. They could cut three keepers in less than three hours. They were used to playing on songs of three minutes or less. Get in, get out, go to the next gig. Dylan didn’t work that way. While he was writing and rewriting his lyrics, hours and hours would go by as the musicians loafed, played ping pong, smoked cigarettes…and waited. As mentioned, only one song, “One of Us Must Know,” was used on the album from the New York Sessions. The others were rerecorded in Nashville. When the task was completed, when the album was finally wrapped and released, the world, with approbation, understood that Dylan and the Nashville cats had succeeded in finding and creating the sound that Dylan had been seeking for some years: That thin, wild mercury sound.

Sanders (b. 1941) is a music historian and he does a fine job here. He doesn’t skimp on facts, he knows his Dylanology, he obviously had established a rapport with all the players and he ties it all up with an evenly paced prose style that tells the story and keeps the pages turning. Recommended.

Sanders (b. 1941) is a music historian and he does a fine job here. He doesn’t skimp on facts, he knows his Dylanology, he obviously had established a rapport with all the players and he ties it all up with an evenly paced prose style that tells the story and keeps the pages turning. Recommended.

* I always was bothered by the line in the song “And the record man said every one is a yellow Sun Record from Nashville….” The original Sun records with the yellow labels all came from Memphis.

** The album credits “Jamie Robertson.” “Robbie” is a nickname. Robertson’s bandmate from The Band, Rick Danko, also played on some of the New York sessions.

Copyright 2019, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter