The Flying Firsts of Walter Hinton

From the 1919 Transatlantic Flight to the Arctic and the Amazon

by Benjamin J. Burns

by Benjamin J. Burns

“Lindbergh always said our mission was tougher than his because airplane engines weren’t reliable in 1919, gasoline frequently had dirt in it and if a motor ran for 10 hours we took it apart to find out why.”

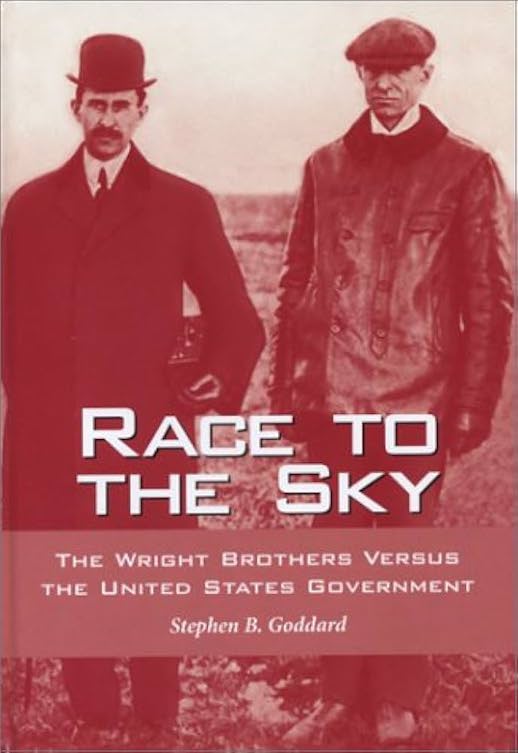

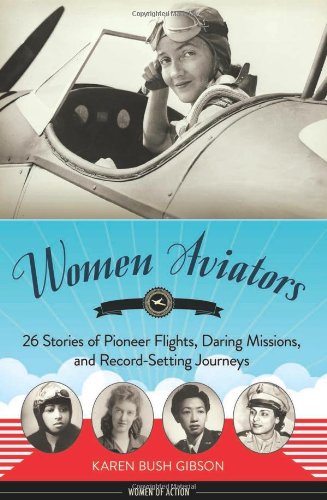

US aviation pioneer Walter T. Hinton (1888–1981) saw it all in his 92 years on this Earth. He knew the Wright brothers and Arctic explorer Richard Byrd (whom he taught to fly) and Atlantic-crosser Charles Lindbergh and flew on the Concorde. In no particular order, he attended the Versailles Peace Conference, discovered white Indians, consorted with royalty, had his second heart attack in 1928, founded the Aviation Institute of U.S.A. to offer correspondence courses to would-be pilots, crashed in a balloon in the wintry Canadian wilderness—and more, more, more. A life fuller than most, and still his name today draws blank stares, even among aviation enthusiasts.

Unless you have absolutely no imagination, between Hinton’s derring-do and Burns’ lucid writing this tale will have you twitching in your chair. Writers, especially of fiction books, always hunger for that all-important opening line, the one that grabs the reader’s attention and sets just the right tone for what is to follow. Burns, who is director of the journalism program at Wayne State University, hit upon a good one: “Flying is an act of faith.” While not an aviator himself, Burns had a keen fascination with flying ever since strapping on sticks and cloth and boldly stepping off the roof—all of six years old.

Considering Burns’ own grasp of Hinton’s achievements it is almost shocking that he set aside for 30 years the material he had first compiled as a newspaper reporter during 40 hours of interviews with Hinton in 1967/68 and fleshed out with hundreds of hours of research in various archives. Hinton was dead almost 20 years before Burns, in 1999, was propelled into finally revisiting the subject by yet another misguided news story of how it was Lindbergh who had crossed the Atlantic first. Lucky Lindy was the first to do it solo and nonstop, but by that time (1927), 90 men had crossed before him in the eight years since Hinton and his crew had done it first.

That feat—and various others such the first flight from North to South America (New York to Rio de Janeiro) or the first aerial mapping of the unexplored Amazon River valley—made Hinton early in his flying career the go-to guy all the newspapers sought out to comment on aviation milestones, which, in the 1920s, seemed to fall every other week.

Burns begins with sketching a deft picture of young Hinton’s personality and interests—only to have a full exploration of it interrupted by Ch. 1, “In the Beginning,” which it isn’t because it fast-forwards to highlights of the 1919 flight that is discussed in three chapters later on. After this distraction, the story arc returns to Hinton’s youth on an Ohio farm and his joining the Navy “to get away from it all.” Since Hinton isn’t a flyer yet, his Navy chapter squeezes in all sorts of aviation activity (Wright brothers, Glenn Curtiss) taking place in the world around him. Thank goodness there’s an Index, even if not very deep, to point you to items the Table of Contents doesn’t or the chapter titles don’t hint at. Since Burns teaches information dissemination one must assume that all this, however impractical, is done intentionally.

The fact that the staggeringly complex transatlantic flight took place a mere two years after Hinton had gotten his wings in 1917 only goes to illustrate how quickly progress was made during that era. In fact, it was only one month later that Hinton’s 19-day effort on which two of three planes were lost was bettered by Alcock and Brown’s nonstop flight. Theirs and other British efforts are covered in two chapters.

Described as a “natural flyer” who could get machines airborne that frustrated other pilots, Hinton is shown as not only a capable aviator but a competent all-round man possessed of a temperament that allowed him to remain at ease in trying and untried situations, the latter also including his unsought celebrity.

An Epilogue addresses Hinton’s will, the disposition of various artifacts and questions of their authenticity, and a few words about various ship- or crewmates. Several pages of Chapter Notes precede a deep Bibliography (giving credence to Burns saying he read everything).

As almost always in books by this publisher, the illustrations are so few as to leave one clamoring for more. For obvious reasons the balloon crash in Canada has the fewest.

Whether you have specific early aviation interests or simply like a great story, this book won’t disappoint.

Copyright 2025, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter