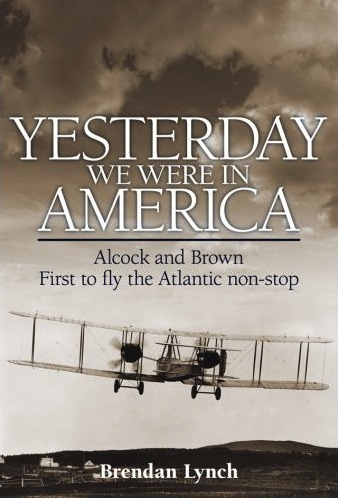

Yesterday We Were in America: Alcock and Brown, First to Fly the Atlantic Non-stop

by Brendan Lynch

by Brendan Lynch

“Yesterday We Were in America!” Imagine saying that at a cocktail party, or to your friends and neighbors—in 1919.

This is in fact the phrase pilot Alcock kept repeating to the crew of the Marconi radio station near which he had landed, and who simply would not believe him until he produced as evidence a sealed mailbag from Newfoundland, his point of departure 1,880 miles back across the Atlantic. This is about as exotic a pronouncement as today saying “Yesterday We Were on Mars!” It was totally unprecedented. It had only been three weeks earlier that an Atlantic crossing by a US Navy flying boat, that in a pinch could have set down on the water and rendevoused with a rescue boat, had concluded—and that had taken 19 days of flying in short stages (for a total of 57:16 hours in the air). And now Cpt John Alcock and Lt Arthur Whitten Brown had done a 1900-mile nonstop crossing from Newfoundland to Ireland, in only 16 hours and in a rickety Vickers Vimy biplane at that.

We live in a world that has in the lifespan of one generation gone from horse-drawn buggy to putting a man on the moon and has seen everyday supersonic civilian air travel come and go. Been there, done that. But a newspaper reader in 1919 would have been overcome with excitement at the novelty of this flight—the longest distance traveled nonstop by man—in a world still new to mechanization in general and aviation in particular. (Recall that the war that had ended a year earlier—the Great War, World War One—had started with horses and ended with tanks!)

And excitement was generated again in 2005. Seeing the Vimy land in Ireland at the end of the reenactment of Alcock and Brown’s 1919 flight by adventurers Steve Fossett and Mark Rebholtz inspired the author to write this book. Lynch tells an engaging story drawing from Alcock and Brown’s own written records, contemporary news coverage, and from eyewitness accounts such as that of the one witness to the 1919 arrival in Ireland who is still alive. (He was seven years old at the time.) Early on Lynch threads the needle of what unlikely heroes these pioneers were so that the reader, at the end, having traveled the full arc, duly commiserates with their tragic end.

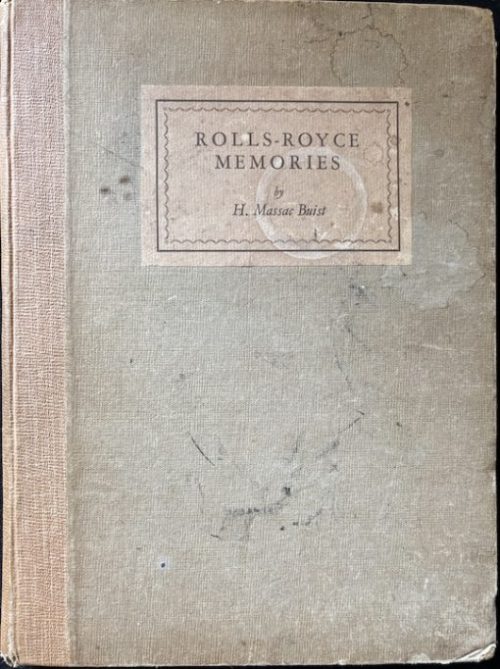

A good amount of background is established by recapping the exploits of balloonists, the Wright brothers, and the national sentiments and political stirrings that resulted in the issuance of a £10,000 (ca. £500,000 in today’s money) challenge from the Daily Mail newspaper. Lynch explains the building of the Vimy at the Vickers plant located on the Brooklands racetrack grounds, and the dominance of the Rolls-Royce Eagle engines (#5244 and 5246 on the Alcock/Brown Vimy) that propelled all but one of the seven contenders for the prize money. (A peripheral but pertinent observation: Readers already familiar with aero engine development will know to dismiss the now debunked story retold here of the influence of the Mercedes engine on Eagle development. Everyone else is encouraged to bone up on this.)

The details of the flight itself will have you twitching in your chair. The story of the aftermath—knighthoods, international acclaim—casts a harsh light on the toll fame takes.

The photos, all b/w, are bundled into two sections. They show what needs to be shown but there is nothing new to the record here (not a criticism, just a fact). A Foreword by Len Deighton, an Appreciation by Steve Fossett, a map, a bibliography of books, a list of news sources (only by name and not specific issue/date or the like), and an index round out the book.

Copyright 2009, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter