British Aviation Posters: Art, Design and Flight

by Scott Anthony and Oliver Green

by Scott Anthony and Oliver Green

“The unhappy saga was a powerful reminder that, while the carriers, planes and organizational norms of British civil aviation may have been increasingly homogenised by a global market, the psychological and emotional need for British civil aviation to retain its own distinct identity remained.”

This is a lovely and interesting book but before you read this review take another look at the book’s title and subtitle and ask yourself what you think it is about. Chances are it is both more and less than you expect. More: it really is the story of an airline and, by extension, the country whose flag it flew. Less: if everything the book says about graphic design and poster art and artists were distilled into one section, it would make up maybe 30% of the book. Nothing wrong with that—just not self-evident, and a reminder that selecting a book solely based on its title is often good for a surprise.

The quote above, from the epilogue, is what the book is really about: the search for an identity in an ever-changing world and attempts at expressing it graphically. The context for the quote is Project Utopia, a surprise effort accompanying Britain’s national airline adopting a new livery in 1997.  It introduced tail-fin art to represent countries on British Airways routes and was intended to move away from the airline’s image as “arrogant and detached.” Seems like a perfectly good idea—but it didn’t “fly” at all, certainly not with the domestic audience, with then-PM Margaret Thatcher going so far as to cover up the tail fin of a model 747 with a handkerchief and complaining “We fly the British flag, not these awful things!”

It introduced tail-fin art to represent countries on British Airways routes and was intended to move away from the airline’s image as “arrogant and detached.” Seems like a perfectly good idea—but it didn’t “fly” at all, certainly not with the domestic audience, with then-PM Margaret Thatcher going so far as to cover up the tail fin of a model 747 with a handkerchief and complaining “We fly the British flag, not these awful things!”

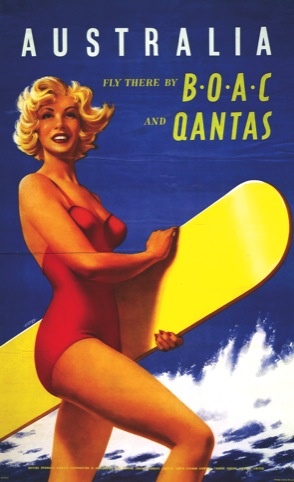

It ain’t easy, you see, to be all things to all people. And it is that aspect that makes the story of civil aviation in Great Britain, that waning Empire with far-flung colonies, so singularly unusual.

Something else not self-evident about this book is that it is commissioned by BA, which is quite a different thing than the discreet little slug “produced in association with British Airways” in the frontmatter would indicate—provided readers notice it at all. It is first and only mentioned at the very back of the book. It wouldn’t strain the imagination to suppose that the publication of the book is connected to BA re-opening in December 2011 its museum at the extensively overhauled Speedbird Centre headquarters.  The Heritage Collection, which houses the artwork shown here alongside many other artifacts, is open to the public only by appointment so this book is a good way to see the posters.

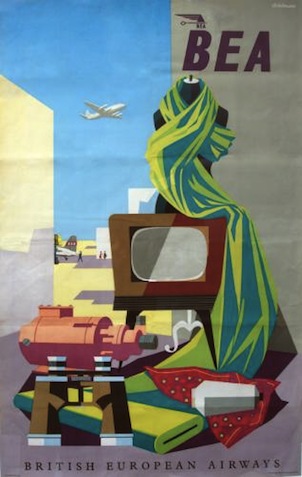

The Heritage Collection, which houses the artwork shown here alongside many other artifacts, is open to the public only by appointment so this book is a good way to see the posters.

It seems prudent to direct the reader to begin with studying the timeline on p. 194/95 to get a first sense for how the airline and its several precursors since 1924 came about, came together, and fits into the larger scheme of things from airplane development to domestic and international political developments.

Both authors have published extensively on transportation subjects, especially in recent years. Green, who penned the first two of three chapters here, is former Head Curator of the London Transport Museum. Anthony, who covers 1950 to the present, is a Fellow at Christ’s College, Cambridge where he researches the growth of the public relations industry—which, naturally, involves artists and intellectuals—in Britain and elsewhere during the twentieth century. Neither of them is an art expert per se but much of their art commentary here involves people and agencies they have encountered in their prior work, especially the London Underground, the railways, and also the steamship lines.  These all predate civil aviation and had grappled with many of the same problems in having to explain themselves to a skeptical public. That said, the art-focused reader will probably find this part of the text a bit lightweight (i.e. technique, style, typography, color, print technology, or even the bios) although the authors, Anthony perhaps a bit more so, make every effort to explain the dynamics and subject matter of specific posters. Likewise the airplane-focused reader will wish for more detail regarding aircraft design and technology (not to mention identification) which the authors feel is “well beyond our areas of expertise.” So, here, too it ain’t easy to be all things to all people.

These all predate civil aviation and had grappled with many of the same problems in having to explain themselves to a skeptical public. That said, the art-focused reader will probably find this part of the text a bit lightweight (i.e. technique, style, typography, color, print technology, or even the bios) although the authors, Anthony perhaps a bit more so, make every effort to explain the dynamics and subject matter of specific posters. Likewise the airplane-focused reader will wish for more detail regarding aircraft design and technology (not to mention identification) which the authors feel is “well beyond our areas of expertise.” So, here, too it ain’t easy to be all things to all people.

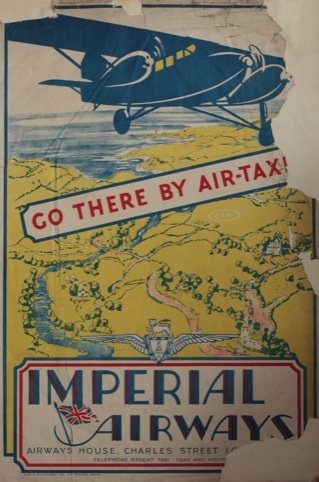

The book begins with a look at the early aviation pioneers and the air shows and races that sought to interest, better yet excite, the public in aviation. Instilling “air-mindedness” was the order of the day, and quickly the focus shifts to the founding of a national airline. As said earlier, this story has aspects that are unique to British conditions. For instance, the government giving precedence to keeping the Empire connected even at the expense of developing domestic or continental aviation has specific consequences both in terms of the apparatus (planes, airports, infrastructure etc.) and, ultimately the subject of this book, the advertising that went with it.

The book begins with a look at the early aviation pioneers and the air shows and races that sought to interest, better yet excite, the public in aviation. Instilling “air-mindedness” was the order of the day, and quickly the focus shifts to the founding of a national airline. As said earlier, this story has aspects that are unique to British conditions. For instance, the government giving precedence to keeping the Empire connected even at the expense of developing domestic or continental aviation has specific consequences both in terms of the apparatus (planes, airports, infrastructure etc.) and, ultimately the subject of this book, the advertising that went with it.

In the course of its examination, no stone is left unturned and even the stewardesses’ attire and the furnishings of the aircraft are assigned their proper place in the story of the ninety years of defining and communicating an international airline’s identity and brand values.

Beautifully designed by Heather Brown the book features many full-page posters (all in color), nicely reproduced and augmented with a multitude of period photos. Appended are Chapter Notes, a timeline, and a quite long list of materials for further reading. Index.

The book is not cheap but takes you to depths you could have hardly suspected from its title alone and offers many hours of fruitful discovery.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Dear Sabu Advani,

Many thanks for such a deft and thoughtful review!