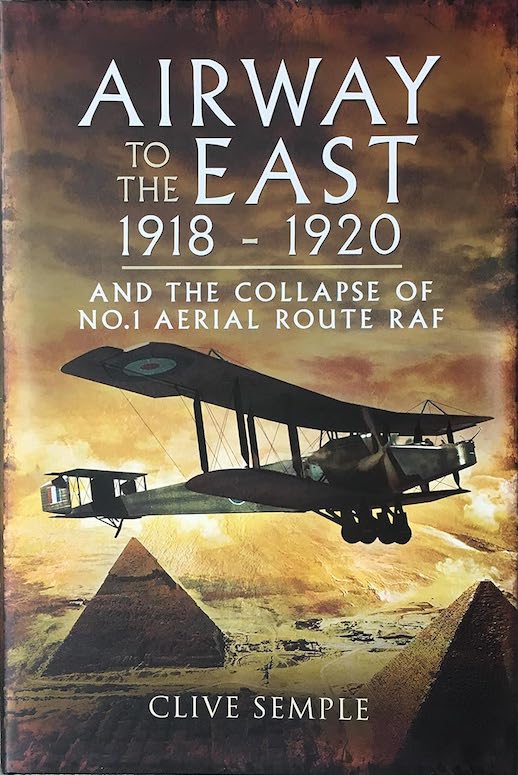

Airway to the East 1918–1920 and the Collapse of No.1 Aerial Route RAF

by Clive Semple

by Clive Semple

“The story remains unknown to the public because it was deliberately suppressed by senior Army and Air Force officers at the time. As far as the author knows this is the first time that the suppressed events have seen the full light of day, although accounts of them are tucked away in files held in the National Archive in Kew and have been available to serious historians for many years.”

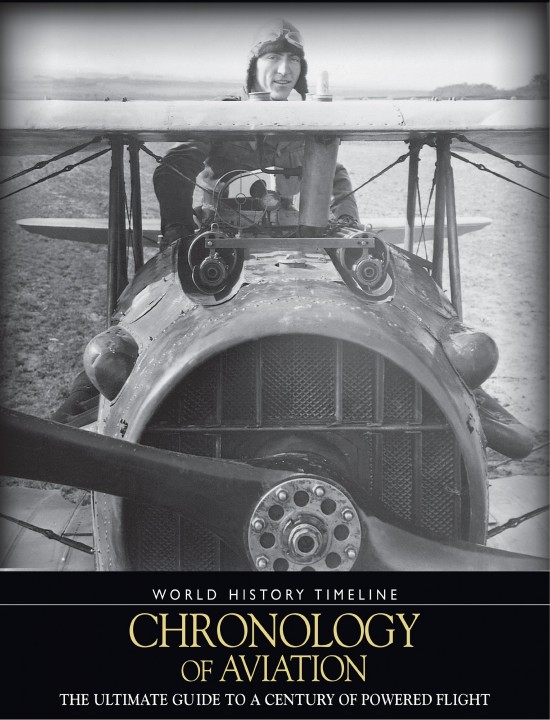

Looking at that book cover doesn’t get old.

Students of British long-distance flying will know of what was called “the first aerial route” which ran from Cairo to India. But the history of the England-to-Cairo leg—aka No.1 Aerial Route—was buried in utter obscurity, until someone chanced upon a paper trail, which resulted in this book.

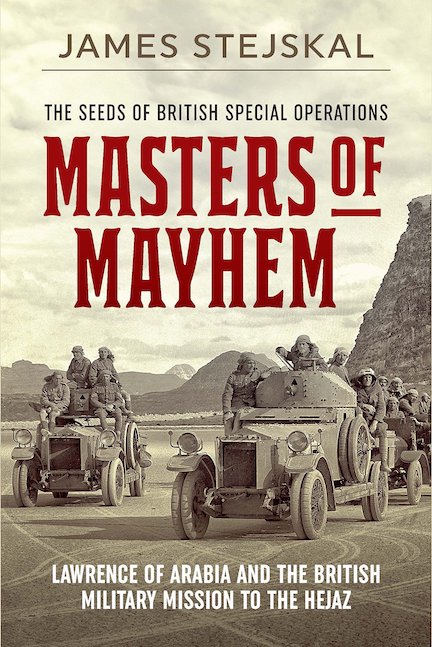

Near the “Lawrence of Arabia” mark on your mental timeline should be another one, for “Balfour Declaration.” These long-ago events shape the world you live in today, in the form of the unending Arab-Israeli conflict. When you’ve finished the book you will wonder if the world would be a better place if the story hadn’t been suppressed all these decades ago. Or better yet, if the events had never happened.

You can “blame” the author for at least 25 of those silent years. The book started simple enough. A man dies, his son sorts through his papers. That was 1971, when Leslie George Semple’s diary, scrapbook, and photo albums were retrieved from his attic by his son Clive—only to be moved to a different attic, awaiting the leisure of Clive’s far-off retirement years to be dealt with in earnest.

Semple Sr. (b. 1899) had joined the Royal Naval Air Service in 1917 and served 1918–1920 on 207 Squadron as a Handley Page O/400 heavy bomber pilot. His 27 night bombing missions over France and Belgium became, after years of research, the subject of Clive’s first book, Diary of a Night Bomber Pilot in World War I (The History Press, 2008). But it was a newspaper clipping in his father’s scrapbook relating to an entirely different matter that set Clive onto a whole new path of inquiry.

That ancient newspaper pertained to the British parliament convening a public Court of Enquiry to investigate why 51 Handley Page bombers en route in 1919 by air from England and France to Egypt had encountered catastrophic losses. Before the enquiry even began, military and political leadership were fully cognizant of the political fallout from its inevitable findings and so barred the public from attending and later sealed its findings. The reason the elder Semple held on to that newspaper was because he had been involved.

Many different strands come together in this story, and the book struggles with dealing with each of them—and so does this review: a new aircraft, internecine strife in branches of the armed services, embattled British troops in far-away Arab lands calling for air support.

Normally, the airplanes would have been sent by boat: four weeks. Quicker to fly them: six days. But how do you get a quantity of large but quite fragile bombers (the wings can’t even support their own weight unless they are specially rigged etc.) that can safely cover only 400 miles at a time from Europe to Egypt without having supply and service facilities along the way? For that matter, what was the way? You can see how this story has all the makings of an uncertain outcome. Aircraft and men were lost, en route to and again at the destination.

To appreciate how explosive this story was then and for many years after, consider that it is completely omitted from the biography of Brigadier Geoffrey Salmond (at the time Middle Eastern Air Officer Commanding who later rose to Chief of the Air Staff) written by his daughter for this same publisher (From Biplane to Spitfire: The Life of Air Chief Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond KCB KCMG DSO, 2003).

To appreciate how explosive this story was then and for many years after, consider that it is completely omitted from the biography of Brigadier Geoffrey Salmond (at the time Middle Eastern Air Officer Commanding who later rose to Chief of the Air Staff) written by his daughter for this same publisher (From Biplane to Spitfire: The Life of Air Chief Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond KCB KCMG DSO, 2003).

As troubled as men like Churchill or Chief of the Air Staff Hugh Trenchard, or Salmond, had to be about the public’s reaction to operational mismanagement, public discussion of the reasons that made the flight necessary in the first place was a greater concern. In a nutshell, Her Britannic Majesty’s government had presumed to have the moral right (obligation?) to “guarantee” the Arabs independence if they would help drive the Turks out of Palestine and Syria. The Arabs did as bidden—not least with the help of the aforementioned T.E. Lawrence who, it happened, was hitching a ride to Cairo on one of the bombers that crashed. But the Arabs ended up denied independence because, having made a different deal—enshrined in the Balfour Declaration—the British now promised the Jews a homeland in Palestine. The consequences of this policy (hubris?) are with us still today.

Students of politics and culture, no matter from which camp, but also students of RAF history will each find different big-picture aspects of Semple’s account lacking in detail, nuance and, therefore, fairness. Those same readers should, however, concede that this is not the story Semple is intending to tell. All these complex issues are merely building blocks to set the scene for the ill-fated flight involving the squadrons of which his father was a part. Based on his first book, and the apparatus to this one, it is reasonable to say that Semple is a proper researcher and that his conclusions are not arbitrary.

The book opens on the crash of Lawrence’s plane and then discusses the bomber itself, in the context of the Royal Flying Corps splitting into a Naval and a Military Wing over disagreements as to each branch’s mission profile. The Arab Uprising (sound familiar??) and the Allenby Campaign strands of the story are introduced and then the focus shifts to the first, single Handley Page bomber seconded to that campaign and the mapping of what would become No. 1 Aerial Route.

The book opens on the crash of Lawrence’s plane and then discusses the bomber itself, in the context of the Royal Flying Corps splitting into a Naval and a Military Wing over disagreements as to each branch’s mission profile. The Arab Uprising (sound familiar??) and the Allenby Campaign strands of the story are introduced and then the focus shifts to the first, single Handley Page bomber seconded to that campaign and the mapping of what would become No. 1 Aerial Route.

After discussing the end of the war with Turkey, culminating in the aptly named chapter “The Arab World Erupts,” we are about 1/3 into the book and the focus shifts to and remains on the planning and execution of the operation to get the bombers and all their support crew to Egypt. The level of magnification is now greater and the pace less hurried.

Throughout, the book is suitably illustrated. Early-aviation enthusiasts will find much of interest. An 8-page color section shows several maps, important locations, and some fine art.

A discussion of the Enquiry and its aftermath precedes an entirely separate part of the story: opening an air route from England to Australia. Even here Semple’s questioning mind finds cause to deviate from established thinking regarding the reasons for the Australian government to stipulate that the winner of its prize had to be Australian, unlike the British prize which had no restrictions.

Not an easy book to compose, surely. Whether you like history, politics, travel or aircraft, this book ticks many boxes. Semple obviously has a particular point of view and it colors his take on “history as we know it,” but for that part of history we would never know if it weren’t for his telling, we just have to follow him. So, yes, not an easy book to compose, surely.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter