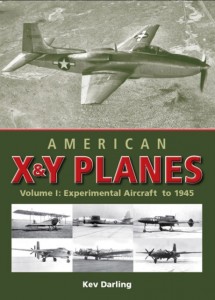

American X & Y Planes: Volume 1: Experimental Aircraft to 1945

by Kev Darling

by Kev Darling

“No matter where you look in the annals of aviation history, it is littered with strange and wonderful aircraft, many of which were evolutionary dead ends.”

Many of the aircraft in this book may not be terribly well known but without them the planes that we do know would probably have not come about. In other words, trial by error. Any results—positive or negative—of an experiment advance the body of knowledge and are necessary steps in the validation process. So, don’t think of these aircraft as “failures” but stepping stones.

This is the first of a two-volume set (Vol. 2 is Experimental Aircraft Since 1945, ISBN 978 1 84797 1470) written by an ex-RAF engineer with many competent aviation titles to his name. This is a worthy and important subject and as there already exists a commensurately large body of literature, it is not easy to assign these two slender books their proper place in the larger scheme of things.

For what they are they’re not cheap so you’ll want to know exactly what these two do that others don’t: they tell the story on the US side and, making their brevity a virtue, are able to offer context by providing a large number of listings. Call them a “concise pocket history.”

Vol. 1, the object of this review, in particular is noteworthy for its summary of the pre-history to the American entrance into the field (1898 U.S. Army experiments, war with Mexico, WW I). All the industrialized nations had their own teething problems conceptualizing aviation, envisioning a purpose for it, articulating an “official” governmental position, and assigning it a priority that would allow the new and untried enterprise to compete for limited funds and resources. America most particularly was a laggard in the field but would, once committed to the cause, advance it like none other. The reader who has only a passing acquaintance with the subject will meet here long-defunct names of companies.

The order in which the manufacturers are described is not readily apparent; they are not in order of first aircraft or proposal, or first flight or company size, or—always a reliable stand-by—alphabetically. Possibly it is by “magnitude of contribution” but even that seems dubious. Obviously, the early days were fertile ones, with developments overlapping each other, so a clear-cut chronology or differentiation may not have seemed desirable to the author but the same approach is taken throughout the book. At any rate, the reader with a methodical mind will probably struggle with this. It is also not apparent why only some aircraft descriptions are augmented with a brief table of specs, and why not at all of them are illustrated. The photos are clear, not too small (but: when wouldn’t bigger be better . . .), and credited. Their captions do contain detail but of the generic kind; in no case are they specific to unique aspects of design and construction of any one aircraft.

The individual aircraft descriptions are, for lack of a better word, “compact” but to the point, and talk, in the context of company history as well as armed services requirements, about the specific issues the new experimental model was meant to address and how, and if, it did that. Almost all of the planes covered here had military origins and applications; where they do exist there is no mention of civilian variants or developments. The Index is brief but does call out all aircraft mentioned.

The scope of the subject makes it difficult to compare this book to the single-topic books of which Darling has done several (seven for just this publisher) and very well, and one hesitates to say that this one is not on the level of the others. Yes, this is an interesting book but at the end of the day it feels like these are merely the notes to a much bigger book.

Copyright 2010, Charly Baumannn/Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter