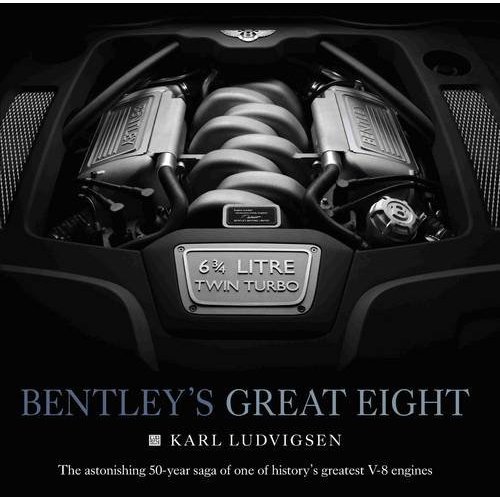

Bentley’s Great Eight: The Astonishing 50-Year Saga of one of History’s Greatest V8 Engines

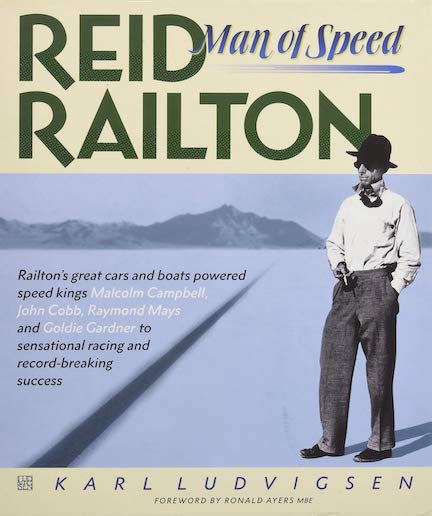

by Karl Ludvigsen

by Karl Ludvigsen

Bentley’s Great Eight? Wait a minute; I thought that was a Rolls-Royce V8 engine! That title is not going to go down well with Rolls-Royce enthusiasts. Since the publisher of SpeedReaders, Sabu Advani, is the editor of the US Rolls-Royce/Bentley magazine and was a contributor to the book in question, we asked him to explain:

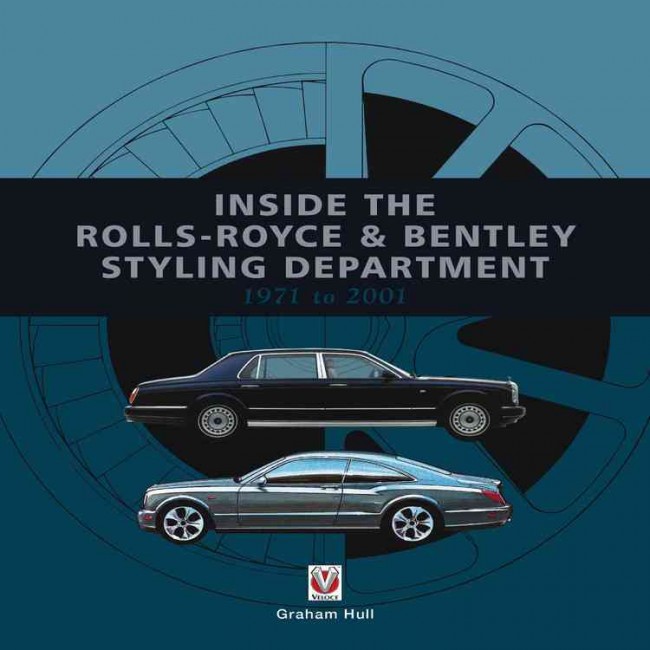

“For much of their lives, Bentley and Rolls-Royce were one and the same company. Obviously author Karl Ludvigsen is aware of that and the omission of the Rolls-Royce name from the title is not an oversight but due to a complicated trademark issue that is not yet fully settled. For all practical purposes, when VW Group acquired the company it became the SOLE owner of ALL physical and intellectual assets and retained them even as it later divested itself of the Rolls-Royce part of the business (to BMW). In legal terms, the history of the engine—an intellectual asset—is thus solely a Bentley property. And so it goes throughout the book; while Rolls-Royce is very much a part of the story, the emphasis throughout is on Bentley. But, it is safe to assume anyone with an interest in reading a technical history of the Crewe V8 engine will be cognizant of the complexities of the name game.” (Also see Comment section.)

So now you know. Another thing you must know about this book is that the scope is limited to engines, and one in particular. At one point, Ludvigsen apologizees for having to explain the chassis changes brought about by the new Turbo-equipped Bentley, as it is not within the scope of the book to include such unrelated topics as chassis or body design and construction. He only refers to those disciplines when absolutely necessary.

Given the resources the company provided the author, some may fear that this book could be a public relations effort, but this is not so. For one thing, Ludvigsen casts a wide net and goes beyond the RR/Bentley world on a wonderful and informative history lesson of the British V8. Little is left out here, and 1/3 of the book is delightfully devoted to the development of the English Eight. He takes us from the promising 1924 Guy, through the ubiquitous Ford flathead, the Riley V8, Autovia, the Raymond Mays, and other V8 contenders up to the Daimler V8 of the 1960s. Second, the book is a deeply technical tome, which is anathema to PR types, who know that talking valve timing and aluminum alloys ain’t gonna play in Poughkeepsie.

After the initial rejection of a very advanced V8 in 1905 (although slated for series production, only three were built before the firm’s marketing strategy switched to a one-model policy), Rolls-Royce did not consider the V8 again until fifty years later, when in the mid 1950s the tried and true RR six was running out of steam. Straight eights and long hoods were out. Although that sounds counter to design efforts which tended to equate long hoods with power and luxury, RR Chief Engineer of Cars, Harry Grylls was more concerned with the “jelly effect” brought about by too much distance between the driver and the front wheels. “We need an engine that can fit within the bonnet of the present car. Go away and think around a 50% increase in power and torque,” was the brief given to Engineer Jack Phillips—who considered it a “dream assignment”—and that is the story Ludvigsen tells.

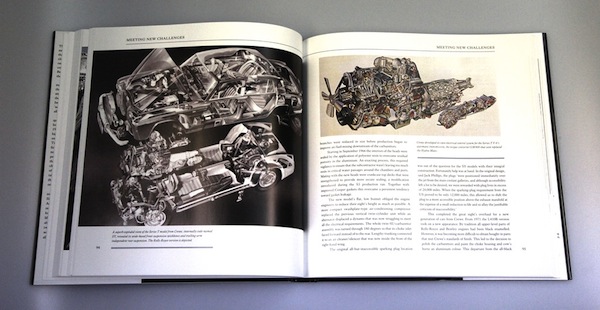

Bentley’s Great Eight is an engine/engineering technical tour de force from beginning to end and a page-turner at the same time—no mean accomplishment. Ludvigsen stops short of bringing math, formulae, or even too many numbers into his writing. In the hands of a less capable writer, the book might easily have become a miserably tiresome compilation of facts and numbers and obtuse technical descriptions. But bringing technical information to life is something Ludvigsen has excelled at since his days at Sports Cars Illustrated where his technical articles on sports and racing cars went far above the norm even for that magazine’s often sophisticated readership.

The author gives us a unique inside look (here looms slightly the dreaded PR but totally necessary for the access) at the process of designing and engineering one of the great engines of the 20th century, whose progeny will extend well into the 21st. Privy to materials from the hallowed halls of Crewe, where the engine was conceived in 1955, using documents written by the engineers responsible for the development of the V8 and interviews with as many engineers as possible, the author brings to light the many critical issues faced by automotive engineers. The history of the Crewe V8 parallels the history of the postwar V8 in general, but with a qualitative difference; Rolls-Royce engines had to be the best, smoothest, and quietest in the world, and do so on a budget so small it would make GM roll over in laughter. Documents show how the Crewe engineers compared their work to other car companies, to what degree they were influenced by Detroit but how they were not allowed to learn the latest lightweight cast iron technology from US makers, which resulted in the decision to use an aluminum block rather than cast iron. “At the time, however, the new foundry techniques weren’t being disseminated by the Americans, who viewed them as a competitive advantage,” writes Ludvigsen. The Brits would learn much but not, it seems, the whole nine yards.

Nevertheless, it was and remains a remarkable powerplant, and today still uses aluminum for the block and heads. From the V8 revolution in the early 1950s to the emission challenges of the 1960s, the gas crisis of the 1970s, to the sudden replacement of carburetors with fuel injection to the era when turbocharging became the only way to increase horsepower without losing economy, the Crewe V8 grew from 183 hp at 4000 rpm on S.U.s to 505 hp, still at 4000 rpm with fuel injection and twin turbochargers. It has had only one increase in displacement, from the original 6322cc to 6752cc in 1971. This motor has been through it all, missing the bullet marked for its demise several times, and its aluminum bottom end has survived much more than just high stresses from the reciprocating masses.

For anyone who considers engineering a passive, not particularly exciting activity, this book will set one straight in a hurry. The decisions and the calculations engineers make can make or break a project and even a company. In fact, I would highly recommend it to any teenager thinking about becoming an engineer, for, as Ludvigsen shows, being an automotive engineer is a high-risk, fascinating, exciting, often dangerous, and ultimately fulfilling career. Perhaps more than anything else, one gains an appreciation of the unusual problems facing engineers. A good example might be the reluctant adoption of aluminum for the engine block based on the premise that the typical Rolls-Royce buyer would not like to wait the extra time for the water to warm the car heater (aluminum dissipates heat faster than iron). Did you ever think the warmth of wingtipped toes might be a showstopper when designing an engine block?

On the downside, if one is not given to enjoy lines like ”Eschewing the drillings to the small ends shown in the 1950 layout, the forged steel rods had a shank cross section, said Phillips, ‘where the fillet radius is large enough to satisfy even the most intransigent forge master,’” the book might be a tough go, at least in parts. Fortunately, the author always looks at the lighter side of life and keeps the prose going valiantly and interestingly even to those who may not have much technical expertise. In addition, the book is superbly illustrated in every important respect, with photos, diagrams, cutaways, charts and drawings that amplify and clarify the text. “How many automobile engines have been granted the honour of a book limning their story?” asks Ludvigsen in the Introduction. Far fewer than one might think, and the Crewe V8 deserves that honor. So, to reiterate, this is not a flashy PR effort destined for the coffee table or the bargain bin. Technical books tend to be set properly on a sturdy bookshelf and used for reference or pleasure and in this case, a good dose of both.

Copyright 2010, Pete Vack (speedreaders.info)

(Vack is Publisher and Editor of VeloceToday.com which specializes in Italian and French cars)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

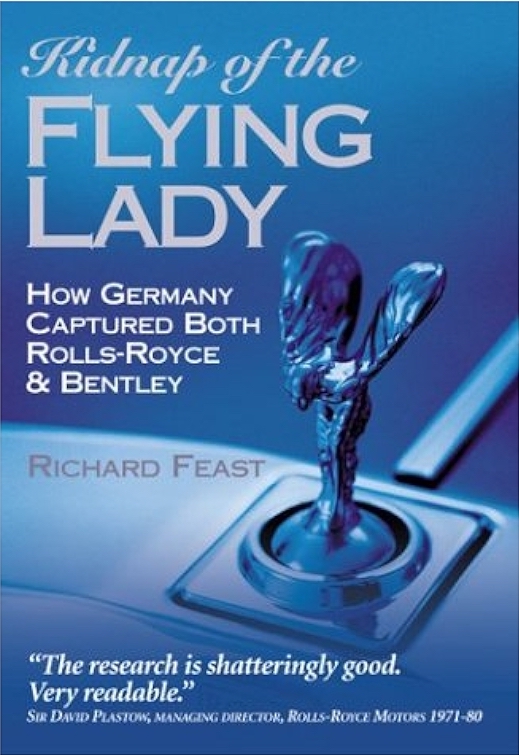

The review opens with a statement regarding the disposition of the trademarks. An entire book was written about that subject, Richard Feast’s 2003 “Kidnap of the Flying Lady”. Written a few years after the 1998 auction sale, and notwithstanding the fact that it won the 2003 UK Guild of Motoring Writers’ Pierre Dreyfus award, its conjecture about the deals before and after the auction and the bidders’ motives are so unverifiable that the book is without merit. The people who were in the room during the negotiations are not at liberty to speak on the record and it will be years, likely decades, before we will learn what really was on VW management’s mind when they willingly paid £430m, acquiring both marques (plus spending another £117 for Cosworth, also then owned by Vickers) and trumped BMW’s competing bid by £90m—only to then roll over without a fight and accede to Rolls-Royce PLC’s pressure to surrender the Rolls-Royce marque to BMW in 2003 for a pittance of some £40m.