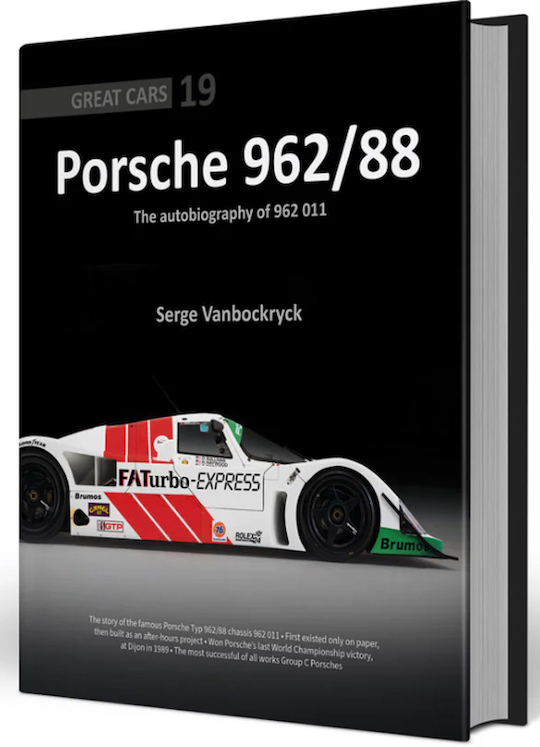

Porsche 962/088 – The Autobiography of 962 011

by Serge Vanbockryck

by Serge Vanbockryck

“Without Reinhold Joest’s efforts, the Typ 962/88 would forever have remained a ‘Paper Porsche.’”

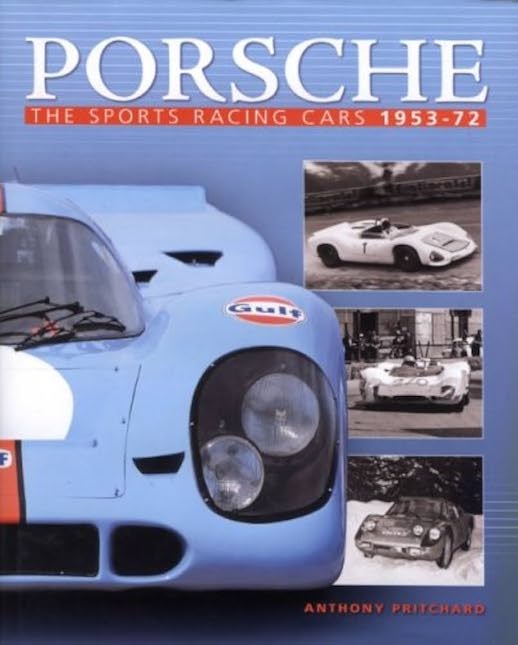

It’s been 43 years since the Group C era began in 1982 but it’s shocking to realize that, 43 years before then, Pearl Harbor was still two years into the future. I watched a high-speed display of Porsche 956s and 962s at Goodwood in 2022 and here’s the thing—these veteran racers from the Reagan/ Gorbachev era (yeah, that long ago) really don’t look as old as they are. The absence of a paddle shift is one of the few reminders that these endurance racers came from an analog era, and were raced by drivers like Ickx and Bell, whose joint age is now 163. WEC, as the former World Sportscar Championship is now known, is in a good place in 2025, with eight big buck hypercar teams. But racegoers d’un certain age still get all misty-eyed about the Group C era, over which the Porsche 956 and its descendants enjoyed almost absolute rule. Sure, the likes of Sauber and Jaguar inflicted the occasional bloody nose on Porsche, but the 956/962 was without question the pre-eminent sports racing car of its era.

This big, colorful, and weighty book from Porter Press is about the history of chassis 962/011, one of the nineteen works 962s, and the most successful. The author has been collecting data on the 200+ 956s and 962s for decades and, like similar books in this publisher’s “Great Cars” series (such as the Brawn BGP 001/02 book I reviewed before), this book will undoubtedly stand as the definitive work on its subject.

While you would have to be a serious student of the 962 to read every word of this hugely detailed book, that isn’t a failing. Sometimes it’s enough to be reassured that, if you need to find out where 962/011 finished in the second race of the Int. ADAC-Bilstein Supersprint at the Nürburgring on 17 May 1992, you can. In case you’ve forgotten, it was second, with Oscar Larrauri of Argentina at the wheel. Even if your interest in the 962 is finite, there’s a whole lot more to read about. The second chapter (“Lorelei”) is about that rarest of events, a Porsche failure which is what happened when Al Holbert persuaded Porsche that Formula One wasn’t the only single-seater show in town. Except history suggests that it sort of was, and what happened to the Porsche effort was not very much . . .

The reader will not find much personal opinion in this book, as it is essentially a dissertation on its subject. But some comments do almost leap off the page, none more so than Vanbockryk’s view on Stefan Bellof, the German driver who commands almost Villeneuve (père) or McRae postmortem adoration. Of Frank Jelinski the author comments that “. . . he regularly beat the revered—and in this author’s opinion somewhat overrated—Stefan Bellof whenever the two met in the same junior competition.” Ouch.

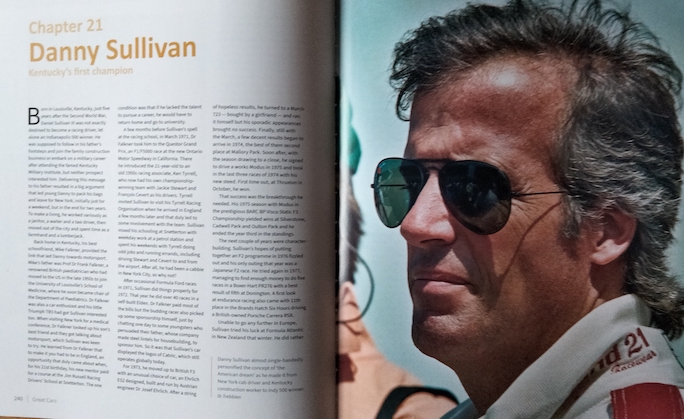

Samuel Beckett’s work is rarely the currency of motorsport books but his most famous play gets a nod in the title of chapter 12, “Godot Arrives.” Who knew that the FIA Interserie Coupe Supersports (etc) championship also featured existentialist angst? They’d ban it in NASCAR, hell yeah. Back to the point—thirteen of the  book’s 26 chapters are 8–10 page driver profiles, each one having raced 962 011 at some point between 1989 and 1993. Even the casual enthusiast is likely to be reasonably familiar with the curriculum vitae of four-time Le Mans victor Henri Pescarolo (“A French Monument”) and Danny Sullivan (of Indy “spin and win” fame) but drivers like John Winter and Jean-Louis Ricci’s stories are rarely told. Ditto for poor Louis Krages, aka “Peter Wood” (rejected as “a giveaway for someone in the timber industry”) and “John Winter” who fell from business success and Porsche racing glory (in 935, 956 as well as 962-11) to penury and suicide. True crime devotees get their fix too—John Paul Jr and his scary dad made the MS in IMSA stand for marijuana smuggling, but the author reminds us just how good a driver Junior was: “one of the greatest American racing talents of his era.” But Senior? He (literally) “sailed away, never to be heard of again” after Colleen Wood disappeared, just as Chalice Paul had done. There’s a whole podcast, right there.

book’s 26 chapters are 8–10 page driver profiles, each one having raced 962 011 at some point between 1989 and 1993. Even the casual enthusiast is likely to be reasonably familiar with the curriculum vitae of four-time Le Mans victor Henri Pescarolo (“A French Monument”) and Danny Sullivan (of Indy “spin and win” fame) but drivers like John Winter and Jean-Louis Ricci’s stories are rarely told. Ditto for poor Louis Krages, aka “Peter Wood” (rejected as “a giveaway for someone in the timber industry”) and “John Winter” who fell from business success and Porsche racing glory (in 935, 956 as well as 962-11) to penury and suicide. True crime devotees get their fix too—John Paul Jr and his scary dad made the MS in IMSA stand for marijuana smuggling, but the author reminds us just how good a driver Junior was: “one of the greatest American racing talents of his era.” But Senior? He (literally) “sailed away, never to be heard of again” after Colleen Wood disappeared, just as Chalice Paul had done. There’s a whole podcast, right there.

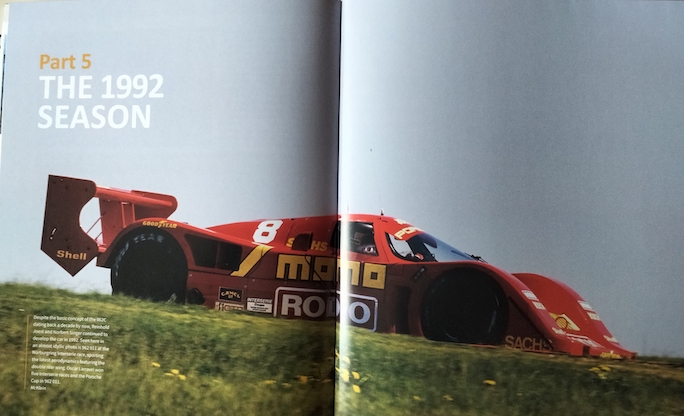

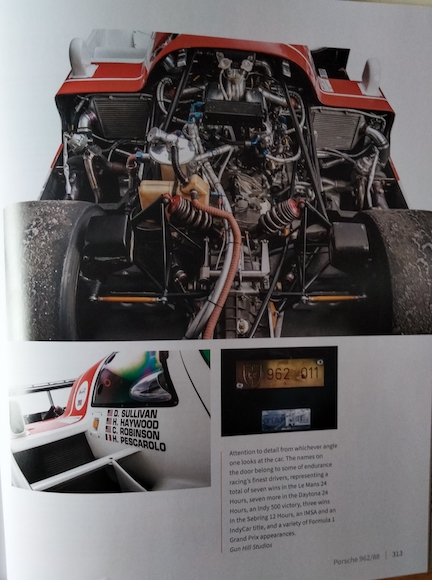

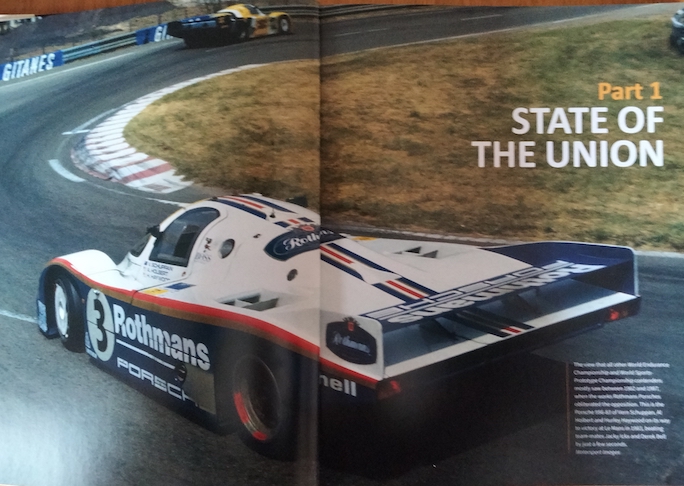

My interest in 962s in general, and 962 011 in particular, is relatively modest, and I confess that I was dreading having to find something interesting to say about the 500+ pictures, many of them of the same race car. But I’d forgotten how successful sports racing prototypes are workhorses, not thoroughbreds, and how they become automotive palimpsests over their long careers. Aerodynamic refinements, a schnorkel here and a NACA duct there, the myriad shapeshifting tucks and tweaks that mean that what is nominally the same car is in fact an eternal work in progress. The liveries exemplify this theme, reminding us that race cars are always just a sponsor’s check away from a new look. For many, the Rothmans colors epitomized the Group C era, thanks not only to on track success but the famous 1987 Duke video (remember them?) In-Car 956. It is now compulsory to term the Rothmans tobacco brand as “iconic” (as nearly everything else is described these days) but the liveries I really loved belonged to sponsors whose existence I was only aware of from race cars, and whose products remain a mystery to me. I’ve no idea what FATurbo EXPRESS, $WAP $HOP, NEW MAN or Taka-Q were selling in the early nineties but their warpaint made Group C races a photographer’s dream. As for the Barbie pink livery sported by 962-011 at Fuji in 1989, because I can’t tell my kanji from my katana, let alone my hiragana, the identity of the sponsor of this kitschfest remains an eternal mystery.

This heavyweight autobiography (get it?) is targeted at the hardcore 956/962 fanbase, in comparison with whom the reviewer is the flightiest of dilettantes. I will admit that my appetite for 962 cuisine has been well and truly sated by chef Vanbockryk’s menu gourmand. But before I lie down, I will say that this forensically researched and richly detailed book is a must-read for those wanting to relive the sturm und drang of sports car racing’s salad days.

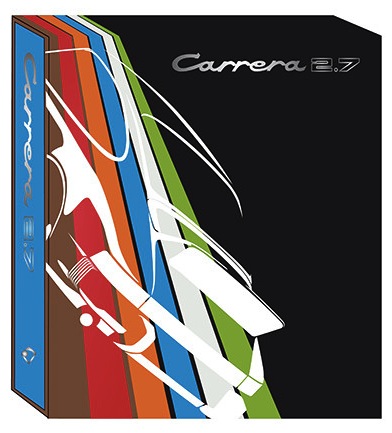

Also available in a limited edition of 50, signed by Norbert Singer and the author, in white leather and slipcased, $475.

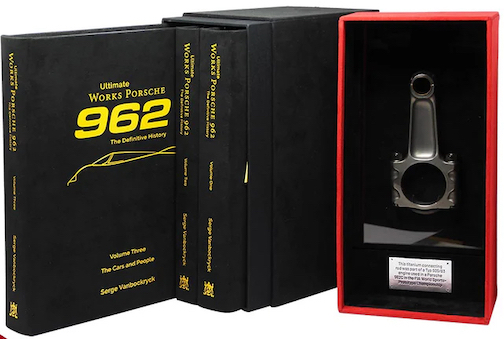

If this one book about one chassis makes you long for a history of all the works 962s, Vanbockryk and Porter Press have you covered there too, with the aptly named Ultimate Works Porsche 962 – The Definitive History. Three volumes, 1400 pages, over 1800 images. (They do the same for the 956.) It is available in three versions, the most lavish being the Owner’s Edition of only 19 sets, autographed by a dozen luminaries. It is handmade to order and rings up at $3,821 because it comes with a certified connecting rod from one of the engines used in a 962C in the FIA World Sports Prototype Championship!

If this one book about one chassis makes you long for a history of all the works 962s, Vanbockryk and Porter Press have you covered there too, with the aptly named Ultimate Works Porsche 962 – The Definitive History. Three volumes, 1400 pages, over 1800 images. (They do the same for the 956.) It is available in three versions, the most lavish being the Owner’s Edition of only 19 sets, autographed by a dozen luminaries. It is handmade to order and rings up at $3,821 because it comes with a certified connecting rod from one of the engines used in a 962C in the FIA World Sports Prototype Championship!

Copyright John Aston, 2025 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter