The Spiders’ Web

by John Bradshaw

by John Bradshaw

Racing cars generally have a short lifetime. Basil Hope Davenport (1903–79) created “Spider” in the UK from a G.N. chassis and engine purchased from its builder, Archie Frazer-Nash, in 1923. Given a generation span of 25 years, the car that Davenport built is about to begin its fifth generation of active competition life. The £105 he paid equates to $8600 now; perhaps enough for a keen 19-year-old to contemplate motor racing.

Author John Bradshaw has absorbed several lifetimes’ experiences and personalities, and has managed to convey these by his book’s layout, with the historical narration interrupted by frequent digressions, and the effect is of a series of conversations amongst friends, with all the laughter such meetings would stimulate.

Your New Zealand reviewer was fortunate enough, after 15 years of absorbing these legends over 12,000 distant miles, to have been present at a 1977 Vintage Sports Car Club racing event at Oulton Park in Cheshire. There, Basil Davenport, by then frail and no longer driving since diabetes had destroyed his eyesight, gave a demonstration of how the grip of sparking plug leads should be supplemented by leather boot-laces, so that the inherently unbalanced V-twin engine of “Spider” was less likely to throw them off. Balance? It didn’t matter much, the object being to spend as little time as possible with the engine running, with the life of the engine measured in minutes before piston seizing or melting, or connecting rod breaking.

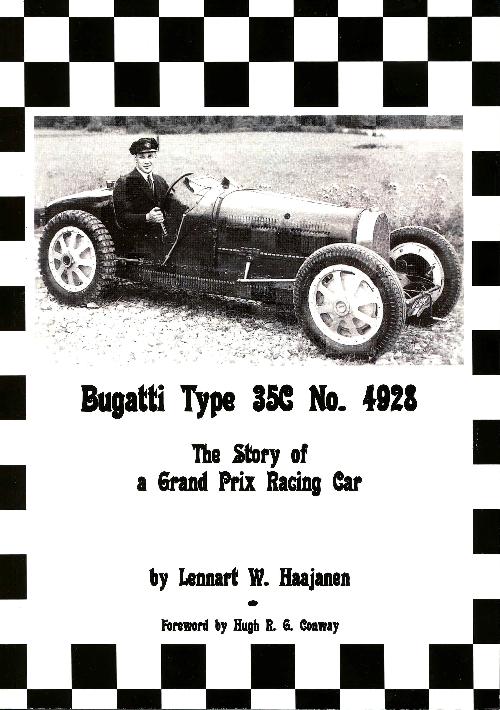

Spider as it first competed, showing the garages from the family home in Macclesfield.

How best to appreciate the conditions of 1909, when Archibald Frazer-Nash (1889–1965) and Ronald Godfrey (1887–1968) went into business to build their G.N.s? Cecil Clutton (1909–90) wrote in Motor Sport, August 1949, “In 1909 motoring was not ‘popular’ or used for business, and was only indulged in by a few of two classes, the rich (with big cars) and the mad (motor-cyclists).” The term “cycle-car” is an obvious description, and the pre-First World War G.N. had a wooden chassis, wire-and-bobbin steering, quarter-elliptic springs fore and aft, a V-twin engine set longitudinally, and final drive by belt. By the time Davenport bought his first touring G.N. 100 years ago, the design had evolved somewhat, with the 90 degree V-twin set athwartships, driving a separate chain for each gear. He competed locally with success in 1922 and ‘23, but the car was being continually developed by the Davenport brothers, with overhead valve cylinder heads, aluminum pistons, altered gear ratios and lightening. Basil Davenport is quoted, “Then at Saltersford I beat a G.N. Vitesse—that was the special sports job—because the hill was too steep for his second gear. I’ve been careful about gearing ever since.”

Davenport was a product of industrial Northern England, where his family had a business of ribbon and elastic manufacturing at Macclesfield; he and his four brothers received their education at those peculiarly British institutions of Preparatory and Public (i.e. Private) schools, the two sisters, Sheila and Brenda presumably being educated appropriately for their sex and social class.

By the time Davenport bought the basis of his “new” racing car from Frazer-Nash, both G.N. partners had left their company, and Frazer-Nash had set up his company to build his own interpretation of the earlier cars. A descendant of his engineering consultancy still exists. Frazer-Nash’s Kim II was copied by the Davenports, but an even slimmer single-seater body was drafted in chalk on the billiard room’s linoleum floor. A minimal amount of ash timber was used to support the aluminum body, which was held to the chassis by just six bolts. This rather battered sharp-prowed body is still in place, almost 100 years later. A visit to Frazer-Nash at his new works secured the 1,086 c.c. overhead camshaft Vitesse engine for £60, and for £90 on a later visit he had the 4-valve, 1,493 c.c. Mowgli. Chain, rather than shaft, drove the cams, and Davenport and his friends modified Mowgli’s so that separate chains replaced the single 6-foot stretch of Frazer-Nash’s design. These friends included the Mucklow brothers, one of whom, Graham (1894–973), became Professor of Engineering at Birmingham University; and Cecil Parker, in whose family another Davenport creation, the BHD Special has remained since Basil’s gift.

By 1924 the pattern was set; sprints and hill-climbs rather than circuits after one race at Brooklands, and always in t’North. There were of course constant development, rebuilds, and experimentation with fuels (of methanol, ether and acetone) and much else. Shelsley Walsh, in Worcestershire, remains the Holy Grail of British hill-climbing, and Davenport by 1926 was able to set a new outright record. In 1930 Shelsley was part of the European Hill-Climb Championship, Rudolf Caracciola (1901–59) with an SSK Mercedes Benz and Hans Stuck (1900–78) in a 3.5L Austro Daimler being present. Spider’s best time of 44.6 seconds beat the Mercedes, but couldn’t match the Austro Daimler’s 42.8 seconds.

With the Great Depression biting, Davenport retired from competition, to concentrate upon keeping the family business afloat. He also married, and his trophies were melted down to become his wife’s jewelry; she found out years later about his “other” career. His occupation was “reserved”, as uniform braid and medal ribbons supplemented wartime demand for elastic. His business ethos could be summed up by his reaction to a suggestion that he patent some of his innovations: “What? And let t’other b . . . s know what we’re doin’? Not b . . . likely!”

In 1946 he didn’t so much as dust off Spider from evidence of 15 years of arachnid and insect activity; more than a wipe with an oily cloth had always exceeded cosmetic preparation. One of the book’s many delightful images shows the delight on his children’s faces as they sit on the newly resurrected Spider. Changes to cylinder heads and tracts for 1931 had been disappointing, and sleeving them down from 2 to 1¼″ provided a short-term solution. Running 11:1 compression and revs up to 5,500, times at Shelsley were good enough to earn Fastest Time of Day for un-supercharged cars that year.

Over the next few years Spider II evolved, with a 2-liter engine of 103 by 120 mm, and an HRG chassis and front brakes bought from his old friend Ron Godfrey, whose post-G.N. career included the marque incorporating not only his initials but those of his business partners Halford and Robbins. Some controversy arose about the chassis dating for Vintage competition, but it was established as one which had sat underneath the bench through the war. Davenport didn’t consider himself as a competitor in Vintage events, but on an equal footing with whoever else was taking part, as he sought the elusive under-40 seconds for Shelsley. In 1962, he achieved 40.69 seconds, but a bad crash at another venue put Spider II and driver out of action. When visited in hospital after broken collar bone, shoulder blade and ribs were attended to, he is quoted as, “Eeh Ron—how good to see you! Tell you what—didn’t the car go well up t’hill on that last run? If we can get it going a bit better we’ll do some good when I’ve rebuilt it.” Imitations of Northern English dialect may be attempted, to accompany Davenport’s customary brown overall coat.

Relegated to Spider I, he achieved their best Shelsley time of 43.98 seconds in 1964, and by 1972 he had been competing for 50 years, finally retiring after the 1975 season. His friend Robin Parker’s account of his 1978 ride up that hill in the two-seater BHD Special is quoted: “‘Where are we now?’ asked Basil. ‘Just passing the Crossing’ I replied. ‘Can I drive?’ —and Basil took over the steering from the passenger seat and proceeded to steer us up the Hill. I just helped up with position reports. Coming out of the Top ‘S’, Basil asked how he was doing: ‘How was my line? Did I get the offside wheel inside the grid?’ Now, that was important to Basil—and of course his steering was perfect. All this showed Basil’s remarkable knowledge of Shelsley as his eyesight was now so poor he couldn’t really see much past the car’s bonnet.”

The elusive sub-40 seconds has been achieved by both Spiders in the hands of subsequent scrupulously selected carers. It’s all here in the book. It is written by a knowledgeable enthusiast, and aimed at others of his ilk. There is no index, but twenty carefully delineated chapters in sort-of chronological order, but with sidebars further illuminating the characters whose lives have been touched by Spider, its builders and antecedents. Although not printed on art paper, the photographs are of as good a quality as could be hoped for. They are supplemented by drawings technical and artistic, as well as many by W. Heath Robinson, who must have been present. His whimsy has gone into the English language, as has Rube Goldberg’s into the American.

Recommended!

Postcript: Following the book’s publication in 2021, the author received a wealth of further information and illustrations. So, using this ‘“new” material, together with material that could not be fitted into the first volume and an update of both Spiders’ ongoing competitions, there is currently a second volume being compiled, to be launched in 2023 to celebrate 120 years since Basil Davenport’s birth and 100 years since the creation of Spider.

There will be virtually no overlap of content with the first volume; format and price will remain. Details to follow in due course.

Copyright 2022 Tom King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter