The Fountainhead

Bussing into the Borough of Manhattan from Union, New Jersey, the highways, dozens of lanes, snake their way in and around each other to finally converge to two lanes into the twilight of the Lincoln Tunnel, and the art-deco towers there have for years reminded me of James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein—a tribute to power and style. The cranes are just off our new Freedom Tower, and the skyline is magnificent, sublime in Kant’s sense of the word, sparkling and gleaming in the sunlight, high and proud and a living symbol of the broad extent of our race, the celebration of the best in humankind. And again, along with the skyline, are those concrete ribbons thronged with speeding trucks, busses and cars, many of them built by folks like Lawrence Hammond, the automotive genius from Ayn Rand’s second opus Atlas Shrugged. I would proudly put a Lincoln Town Car, the sedan, or even the new Town Car, an SUV, up against a Hammond Special any day of the week; only thisis contemporary reality, not the elegantly tough and equally sublime, as in Goethe’s sense of the word, dreams and aspirations of this talented and often misunderstood author, misunderstood by them all, from the far left to the far right and everybody else in between.

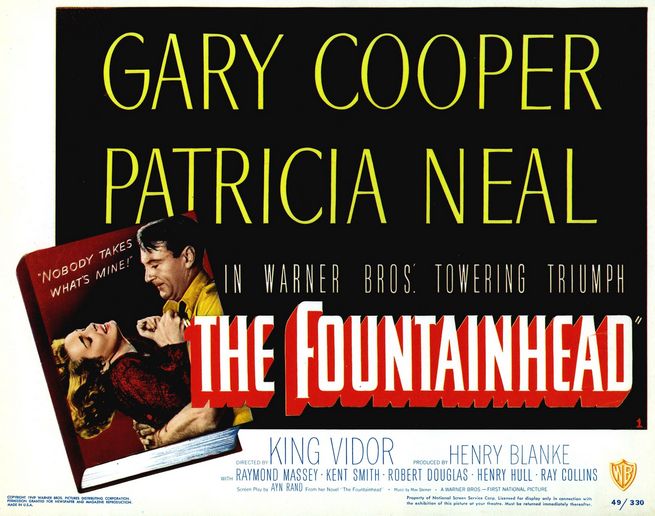

When they made the movie of Fountainhead way back in 1949—I was a toddler then and the book had debuted six years before—just the fact that Hollywood put up Gary Cooper as Rand’s stalwart hero, the architect Howard Rourke, shows prima facie that director King Vidor either had remained clueless, or that decisions had been made above his head [1]. Literary critics and contemporary philosophers have been smearing, or more often ignoring, Rand for decades as the Ayn Rand Institute prospers and Rand’s books continue to sell in the hundreds of thousands of copies. Politicians have been both helped in their careers and/or have deluded themselves into using Rand’s often cockeyed, muddy theories to substantiate their political position. Those malcontents who lock themselves away in remote cabins in remote woodlands, stocking the cabin with semi-automatic weapons awaiting the return of the FBI, would probably breathe in Rand heavily, contentedly, but they would probably miss the point too. To say, then, that Rand, her novels, her politics, her philosophy, her influence, are hopelessly convoluted, contrary, misunderstood, misappropriated, and, yes, even rock solid and on the mark at times, is stating the obvious.

When they made the movie of Fountainhead way back in 1949—I was a toddler then and the book had debuted six years before—just the fact that Hollywood put up Gary Cooper as Rand’s stalwart hero, the architect Howard Rourke, shows prima facie that director King Vidor either had remained clueless, or that decisions had been made above his head [1]. Literary critics and contemporary philosophers have been smearing, or more often ignoring, Rand for decades as the Ayn Rand Institute prospers and Rand’s books continue to sell in the hundreds of thousands of copies. Politicians have been both helped in their careers and/or have deluded themselves into using Rand’s often cockeyed, muddy theories to substantiate their political position. Those malcontents who lock themselves away in remote cabins in remote woodlands, stocking the cabin with semi-automatic weapons awaiting the return of the FBI, would probably breathe in Rand heavily, contentedly, but they would probably miss the point too. To say, then, that Rand, her novels, her politics, her philosophy, her influence, are hopelessly convoluted, contrary, misunderstood, misappropriated, and, yes, even rock solid and on the mark at times, is stating the obvious.

One way to appreciate Fountainhead is to appreciate Rand’s substantial belief in the glory of modern skyscrapers—remember that skyscrapers were a relatively new phenomenon during her formative years. The New York skyline readily evokes a sense of wonder and a grand admiration for the engineering and aesthetic pinnacle of mankind. Although her take on this is extravagant, it has merit. Listen to Rand speaking through the ennobled and enraptured Fountainhead’s Gail Wynand:

“I would give the greatest sunset in the world for one sight of New York’s skyline. Particularly when one can’t see the details. Just the shapes. The shapes and the thought that made them. The sky over New York and the will of man made visible. What other religion do we need? And then people tell me about pilgrimages to some dank pesthole in a jungle where they go to do homage to a crumbling temple, to a leering stone monster with a pot belly, created by some leprous savage. Is it beauty and genius they want to see? Do they seek a sense of the sublime? Let them come to New York, stand on the shore of the Hudson, look and kneel. When I see the city from my window—no, I don’t feel how small I am—but I feel that if a war came to threaten this, I would throw myself into space, over the city, and protect these buildings with my body.”

Wynand is Dominique Francon’s second husband. Francon is the complex heroine of the book. She is strong-willed, rebellious, independent and psychologically unhinged— nonetheless amazingly admirable, interesting, and likeable. Her love for Rourke blooms after being date-raped by him, and she ferociously admires his work and exalts it over and above the work of her first husband, Peter Keating, another architect, untalented but successful, one relying on a mash-up of traditional styles to create ugly yet critically acclaimed buildings, buildings that are the absolute opposite of Rourke’s sleek, uncluttered, unappreciated masterworks. Yet due to her twisted priorities, she, working for Wynand’s powerful, influential, sleazy, yellow newspaper The Banner, she does all in her power to keep Rourke from achieving the fame and fortune he so deserves. If you find this melodramatic, consider why Francon marries Keating. She goes beyond detestation of the man; she finds him colorless and irrelevant, making any show of revulsion or hatred immaterial. Rejecting the love offered by the patient, pure, good, selfless and long-suffering Catherine Halsey, Keating marries Francon because he is smitten both by her physical beauty and her icy glamour. Francon marries Keating to debase herself. Needless to say, she, although always correct and agreeable towards him, makes Keating’s life a vale of misery. His misery, along with his oblivion as to Francon’s means and ends, increases when Francon agrees to becomes Wynand’s temporary mistress in exchange for hiring Keating to design and construct Wynand’s latest real estate development. Unnerved, confused and puritanical concerning this offer, Keating’s greed for money and notoriety overcomes any hesitation or pride and so he agrees to the proposition. Francon’s complicity in this affair is once again tethered to her need for self-abasement, but she soon finds Wynand, rather than being the epitome of vulgarity and apathy as his public persona constantly implies, a refined and artfully gifted man, intelligent, a man of taste. She divorces Keating and marries Wynand. Keep in mind, this all the while being Rourke’s sometimes lover even as she continues to try to ruin him. When Wynand finally breaks down and commits an act of cowardliness, Francon breaks off the marriage. Eventually she marries a third time, but I prefer not to give up Fountainhead’s ending.

So—is this novel histrionic enough? Does it make Grace Metalious’ Peyton Place or even Henry Miller’s Sexus pale by comparison? Rand’s characters are often criticized for being wooden puppets, all talking in a monotone sameness spouting Rand’s philosophical and political ideals, and there is truth to these allegations. However, these characters, in the complexity of their psychological makeup, their larger-than-life symbolic purpose and their just plain coolness factor, a mix of camp and mythology, continue to ensure the popularity of The Fountainhead. If you can momentarily put your political and philosophical prejudices aside, you will be ready and able to readily enjoy it. Think of it as a great summer shore read.

There are many editions of this book but this one has Rand’s own notes on the writing of it.

- According to Barbara Branden, in her book The Passion of Ayn Rand, Rand herself had wanted Cooper to play Rourke. Go figure.

Copyright 2013, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter