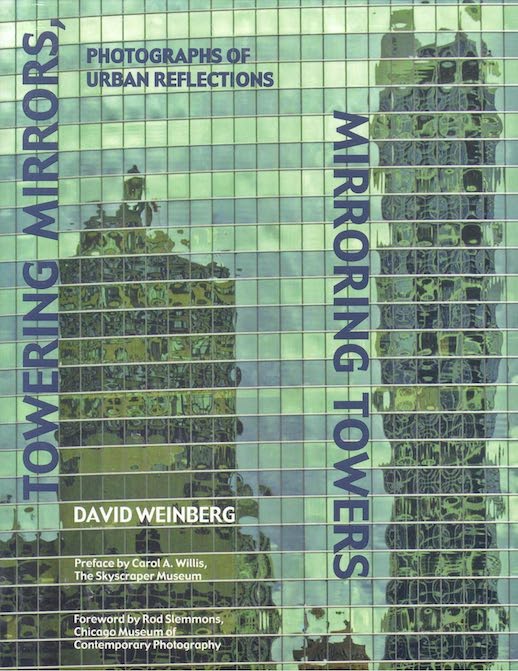

Towering Mirrors, Mirroring Towers: Photographs of Urban Reflections

by David Weinberg

by David Weinberg

Tall buildings are remarkable on so many levels: as a very specific solution to a very specific way of living, as functional art, as “art” art, as engineering marvels. City dwellers see them every day, so much so that skyscrapers simply recede into the background and become part of the visual noise we tune out. Through the camera lens of Chicago native and resident David Weinberg, this book offers a reset.

You’re a reader or you wouldn’t be on this site; as a reader you know that you can read a word even if some letters are missing. Can you “read” a building too if some of its parts are missing? Jumbling the building blocks of words and buildings gives us an opportunity to see them anew instead of instinctively reconstituting the blanks from our experience.

“Visual abstraction” is the language spoken here. As Rod Slemmons (Director of the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago) points out in his Foreword, as a medium, photography has long struggled with the tension between being expected to record unadulterated reality versus its inherent capability of expanding or restating reality by introducing intentional estrangement. American Abstract Expressionism is a well-practiced and -recognized art form—just not in the field of photography.

The Preface, by the director of New York City’s Skyscraper Museum, Carol Willis, brims with collegial largesse and accords Chicago its proper premier place in skyscraper history. As a result of the Great Fire of 1871—17,5000 buildings on more than 2,000 acres destroyed and a third of the population homeless—the city had to rebuild in a hurry. Some of the pioneering techniques became industry standards, and the Chicago frame (steel skeleton) and the Chicago window in particular are among the features that would make possible the glass boxes—first tinted then mirror—that Weinberg plays with here.

The photos celebrate the art of the tall building but if that were all, it would be just another same-old same-old coffee-table book. Weinberg instead recognizes them as “accidental mirrors” that thanks to light, weather, and surroundings display an ever-changing panorama, sometimes only for a fleeting moment. Some of the buildings are blue-blood signature creations by “big name” architects—you’d recognize them if you stood in front of them (Chicago, Dallas, Milwaukee, Elkhart, Sarasota) but you probably won’t in this book. Therein lies the point of this exercise: to see anew.

The photos celebrate the art of the tall building but if that were all, it would be just another same-old same-old coffee-table book. Weinberg instead recognizes them as “accidental mirrors” that thanks to light, weather, and surroundings display an ever-changing panorama, sometimes only for a fleeting moment. Some of the buildings are blue-blood signature creations by “big name” architects—you’d recognize them if you stood in front of them (Chicago, Dallas, Milwaukee, Elkhart, Sarasota) but you probably won’t in this book. Therein lies the point of this exercise: to see anew.

The book is divided into four sections, each having a common denominator and illustrating variations of the same. Because of the way it is manufactured, window glass is usually not perfectly flat. The resulting reflections are further distorted by momentary wind/air pressure on a particular panel. From totally warped fun-house mirror effect to extreme close-ups and crops to kaleidoscopic mirror images of mirror images, you’ll come to appreciate that visual laziness is not a virtue.

All the full-page photos are shown as thumbnails at the back of the book along with city and film/lens information. Since schooling the viewer’s eyes is the desired effect here, it is puzzling why the name of the building or the street address isn’t listed. What could have been better than to have the viewer be able to stand in front of the building, book in hand, and compare realities?

All the full-page photos are shown as thumbnails at the back of the book along with city and film/lens information. Since schooling the viewer’s eyes is the desired effect here, it is puzzling why the name of the building or the street address isn’t listed. What could have been better than to have the viewer be able to stand in front of the building, book in hand, and compare realities?

This is Weinberg’s first book but probably not his last. His distinctive style of photo-abstraction has been on his mind for a while and after leaving the corporate world he ran an eponymous fine art gallery in Chicago that as of 2011 changed into a studio for his photography.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter