Cosmos

“THE COSMOS IS ALL THAT IS OR EVER WAS OR EVER WILL BE. Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us—there is a tingling in the spine, a catch in the voice, a faint sensation, as if a distant memory, of falling from a height. We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries.”

—“The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean,” p. 4

These opening words from the book and the television series make it clear that this isn’t going to be dry science but an experience that is as personal to the reader as it is to the writer.

Cosmos: A Personal Voyage first aired as a thirteen-part TV series on September 28, 1980 with the final episode airing on December 21, 1980. Cosmos, the book (sans “A Personal Voyage” in the title) was released on October 12, 1980. It went on to be the best-selling science book ever published in the English language at the time. The series was broadcast again in 1983 and was later released on VHS, then Laserdisc, and later DVD.

Cosmos the book and television series is generally credited to Carl Sagan. However, the series’ writing is credited to Carl Sagan along with Ann Druyan and Steven Soter, while the book is solely credited to Sagan. In the book’s introduction he explains that the “book and the television series evolved together. In some sense each is based on the other.” Soter is an astrophysicist. Druyan attended New York University but never earned a degree, but her continuing self education and compatible sensibilities brought her into Sagan’s circle and they were married in 1981. How this joint authorship translated onto the screen and the pages of Cosmos is unclear, but likely of marginal consequence, as Sagan (the astronomer, astrophysicist, Pulitzer Prize-winning author etc.) is clearly the headliner and neither Druyan nor Soter have drawn lines around style or content accruing to them and away from Sagan.

In 2014, a new thirteen-part television series called Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey first aired March 9 and ran through June 8. Carl Sagan died on December 20, 1996 so only Druyan and Soter are listed as writers. The new series follows a similar format to the original with thirteen episodes, hosted by astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, who met and was influenced by Sagan as a teenager. This comes on the heels of a new softcover release of Cosmos by Ballantine Books on December 10, 2013, this time with a foreword by Druyan and “Reflections on Carl Sagan’s Cosmos” by Tyson. The rest of the book is the original Cosmos text, with no new text from the 2014 series.

So is this a review of a book or books? or a television program or programs? All of the above points to more than a book—and more than a television program. Cosmos grew and wove itself into the culture until the word “cosmos” became more closely associated with Sagan than with the universe that is its definition. The Cosmos phenomenon even permeated comedy, where Sagan’s voice would be routinely mimicked saying “billions and billions and billions…” which, incidentally, he never did say sequentially in that way but he cleverly used it as a title for a book years later. With this there are endless reviews and commentaries on all the Cosmos media over the last thirty-plus years.

What does it all mean? Why should you care? Is it worth getting a copy of a thirty-year old science book or film?

In short, the central revelation of Cosmos is that we are one with the universe. And its central success is how it demonstrates and defines that “oneness” with its science story-telling, its history story-telling and, yes, its spiritual story-telling. Perhaps this last “success” is the one Cosmos aims hardest at—not as a “religion” but such that the reader and viewer can “fall in love” with the wonders of the cosmos, and thus with the wonders of our humanity and our place within the cosmos. A story told in the context of a journey through the beginning of time, tempered by the universe as revealed by science and the struggle of life to emerge, evolve, culminating in our enlightenment, and our challenge to survive as a civilization.

So to be as practical and relevant as possible, this is a collective review of all the Cosmos media. Carl Sagan was a self-proclaimed popularizer of science. He viewed this as a very serious enterprise, as he believed that the best way to ensure the survival of our civilization is to have a populace that is familiar with science and, perhaps more importantly: how it works, i.e., the scientific method, which he proclaimed is applicable to everything. There are examples throughout Cosmos that speak to this point. A great deal of the series and the book share almost exactly the same text. The book has the advantage of being able to digress into more detail, complete with appendix and index. At times, the divergence in text is pronounced, if not in substance, then in the difference between colloquial speech and what becomes diligently edited grammar for a book.

The book’s thirteen chapters are named and follow the television series’ thirteen episodes, with the odd exception that chapter of the book is titled Travels in Space and Time while the corresponding TV episode is titled Journeys in Space and Time. (And on the DVD, the label says “Travels” while the episode still says “Journeys”… go figure.) So, unless otherwise noted, “episodes” will refer to both the book and the series, and quotes throughout will be credited to their source. The first episode sets the stage for what will follow, and how it will be approached. The last episode is almost a reprise of the first, but now informed by all the material covered in between. There are various episodes devoted to the exploration of planets and celestial bodies, and others with biology and other historical and scientific subjects. A storytelling rhythm is omnipresent. To put all of creation in context, the entire history of the universe is discussed as if it took place over a calendar year—in such a scheme, all of human history would fit into the last few seconds of December 31!

The book’s thirteen chapters are named and follow the television series’ thirteen episodes, with the odd exception that chapter of the book is titled Travels in Space and Time while the corresponding TV episode is titled Journeys in Space and Time. (And on the DVD, the label says “Travels” while the episode still says “Journeys”… go figure.) So, unless otherwise noted, “episodes” will refer to both the book and the series, and quotes throughout will be credited to their source. The first episode sets the stage for what will follow, and how it will be approached. The last episode is almost a reprise of the first, but now informed by all the material covered in between. There are various episodes devoted to the exploration of planets and celestial bodies, and others with biology and other historical and scientific subjects. A storytelling rhythm is omnipresent. To put all of creation in context, the entire history of the universe is discussed as if it took place over a calendar year—in such a scheme, all of human history would fit into the last few seconds of December 31!

Most if not nearly all of the science in Cosmos remains valid. Perhaps the one marker that locates Cosmos most in the late 1970s is its activist, Cold War-era reflection upon the threat of nuclear holocaust. In one sequence, Sagan recounts a “bad dream” that ends with a full nuclear exchange and the destruction of humanity in the ultimate misuse of science, leading to this often quoted line: “We accepted the products of science, we rejected its methods.” It could be argued that our times are just as challenged, only with different threats. In either case, Sagan’s remedy of an informed populace retains its relevance.

Continuing to move on from the science of Cosmos, here are a few glimpses into those more visceral themes, using quotes from Sagan. As mentioned, at the start of journey we’re told what the road will look like:

“We wish to pursue the truth no matter where it leads but to find the truth we need imagination and skepticism both, we will not be afraid to speculate but we will be careful to distinguish speculation from fact. The cosmos is full beyond measure of elegant truths, of exquisite interrelationships, of the awesome machinery of the nature.”

(The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean 5:26)

Here, in our time, these rules of science: “there are no sacred truths” and “arguments from authority are worthless” are worth heeding, particularly as politicians continue to apply political and religious rhetoric squarely onto scientific subjects:

“There is no other species on Earth that does science. It is, so far, entirely a human invention, evolved by natural selection in the cerebral cortex for one simple reason: it works. It is not perfect. It can be misused. It is only a tool. But it is by far the best tool we have, self-correcting, ongoing, applicable to everything. It has two rules. First: there are no sacred truths; all assumptions must be critically examined; arguments from authority are worthless. Second: whatever is inconsistent with the facts must be discarded or revised. We must understand the Cosmos as it is and not confuse how it is with how we wish it to be. The obvious is sometimes false; the unexpected is sometimes true.”

(Who Speaks for Earth? p. 333)

One big divergence between the book and the TV series occurs right at the beginning of the penultimate episode: Encyclopedia Galactica. Sagan, who believed in the existence of extraterrestrials based on the mathematical probablity (given the size of the universe, it seems far more likely that it is populated by life than not), was a harsh debunker of UFO claims. The TV episode begins with a sequence that culminates with the debunking of a major UFO abduction story, giving rise to this often quoted line from Sagan: “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

There are other divergences, such as Sagan’s use of epigraphs to launch each of the book’s chapters—with one exception. In the final episode (and not in the book), it begins with: “I call heaven and earth to witness against you this day, that I have set before thee life and death, the blessing and the curse: therefore choose life, that thou mayest live, thou and thy seed.” This moving quote is not cited as delivered in the episode with an echoing godly voice, but it is, of course, the voice of Jehovah from the biblical book of Deuteronomy (30:19). Sagan, the agnostic, has every comfort in calling on the Deity to persuade humanity away from destruction: “to choose life.”

The destruction of the great Library of Alexandria in ancient Egypt is one prime example Sagan uses and reprises to illustrate the dangers, as mentioned earlier, of an uninformed populace. It’s not hard to see that these shortcomings have survived in various degrees into our time. Referring to that ancient time and place:

“Science and learning in general were the preserve of the privileged few. The vast population of the city had not the vaguest notion of the great discoveries being made within these walls, how could they? The new findings were not explained or popularized. The progress made here benefited them little. Science was not part of their lives. The discoveries in mechanics, say, or steam technology mainly were applied to the perfection of weapons, the encouragement of superstition, to the amusement of kings. The scientists never seemed to grasp the enormous potential of machines to free people from arduous and repetitive labor. The great intellectual achievements of antiquity had few practical applications. Science never captured the imagination of the multitude. There was no counterbalance to stagnation, to pessimism, to the most abject surrender to mysticism. So when, at long last, the mob came to burn the place down, there was nobody to stop them.”

(Who Speaks for Earth? 30:27)

“We have far surpassed the science known to the ancient world, but there are irreparable gaps in our historical knowledge. Imagine what mysteries of the past could be solved with a borrower’s card to this library. For example, we know of a three-volume history of the world, now lost, written by a Babylonian priest named Berossus. Volume one dealt with the interval from the creation of the world to the great flood, a period that he took to be 432,000 years or about 100 times longer than the Old Testament chronology. What wonders were in the books of Berossus!”

(The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean 48:18)

“The loss was incalculable. In some cases we know only the tantalizing titles of books that had been destroyed. In most cases we know neither the titles nor the authors. We do know that in this library there were 123 different plays by Sophocles, of which only seven have survived to our time. One of those seven is Oedipus Rex. Similar numbers apply to the lost works of Aeschylus, Euripides, Aristophanes. It’s a little as if the only surviving works of a man named William Shakespeare were Coriolanus and a Winter’s Tale, although we had heard that he had written some other things which were highly prize in his time, plays called Hamlet, Macbeth, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Julius Caesar, King Lear, Romeo and Juliet.

[dramatic pause]

History is full of people who out of fear or ignorance or the lust for power have destroyed treasures of immeasurable value which truly belong to all of us. We must not let it happen again.”

(Who Speaks for Earth? 35:15)

Then, after this tragic and somber cautionary tale, Sagan aims to recover with an uplifting sequence:

“We have considered the destruction of worlds and the end of civilizations, but there is another perspective by which to measure human endeavors… let me tell you a story about the beginning…”

(Who Speaks for Earth? 37:03)

And it will end in a triumphant message of accomplishment and hope.

Is all that too much? Not what you expected from a bestselling science book? Well, let’s go back to some of the science then.

One of the most missed opportunities from a wide range of other science documentaries is a clear explanation and illustration of scale, size, and numbers. Close your eyes and draw a mental image of our solar system with the planets orbiting the sun. Chances are that what you’re seeing—what has been fed to you visually all your life—is supremely wrong. If the Earth was 1 foot in diameter, its orbit around the sun would be just shy of 15 miles in circumference. You would never know that watching most science documentaries. But in a passage in the episode (and book chapter) Heaven and Hell, Sagan clarifies by writing: “In any model of the solar system it is impossible to show the sizes of the planets on the same scale as their orbits, because the planets would be almost too small to see. If the planets were really shown to scale, as grains of dust, we would easily note that the chance of collision of a particular comet with the Earth in a few thousand years is extraordinarily low.” Next, close your eyes and picture an atom. Now you can see it, with the spherical electrons orbiting a pile of other spheres, protons and neutrons, globed together—the so called nucleus. This too is supremely wrong. The perception of solidity is grounded in the repulsion of electrons in the outer electron cloud. Sagan focuses on this in The Lives of the Stars:“Atoms are very small—one hundred million of them end to end would be as large as the tip of your little finger. But the nucleus is a hundred thousand times smaller still, which is part of the reason it took so long to be discovered. Nevertheless, most of the mass of an atom is in its nucleus; the electrons are by comparison just clouds of moving fluff. Atoms are mainly empty space. Matter is composed chiefly of nothing.” Understanding big numbers is a challenge. In the same episode, Sagan tells the story of how an “American mathematician Edward Kasner once asked his nine year-old nephew to invent a name for an extremely large number—ten to the power one hundred (10100), a one followed by a hundred zeros. The boy called it a googol.” [Hmmm… might be a good name for an internet search engine, no?] Then there’s the “googolplex”—ten to the power of a googol, a ten followed by a googol zeros. Sagan goes on to say “the total number of elementary particles—protons and neutrons and electrons—in the observable universe is about 1080… A googolplex is precisely as far from infinity as is the number one. We could try to write out a googolplex, but it is a forlorn ambition. A piece of paper large enough to have all the zeroes in a googolplex written out explicitly could not be stuffed into the known universe.” These things, and facts like them, are keenly important to understanding science—they are the things that lie beyond our senses and experiences, but knowing them helps us understand when; to reprise: “The obvious is sometimes false; the unexpected is sometimes true.”

Cosmos: A Personal Voyage featured the groundbreaking use of computer graphics. The recreation of the Library of Alexandria was almost completely computer generated. In each of those instances, whether it was the Library of Alexandria (which was clearly represented as a recreation) to the graphics of a DNA molecule, there was no mistaking what was being viewed: an interpretation of reality.

Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey has far more engaging and elaborate use of computer graphics. It is so good, in fact, that it is, unfortunately, misleading at times. The construction of replicating DNA is so artfully executed that one would think it is a completely visually true representation. But this new journey is compelling and worth taking. It carves its own space.

It all that still too much? Then, “more prosaically” (another Saganism), Cosmos is this: everything you should have learned in school but that you may not have been taught, or that you have forgotten. Devote thirteen hours to sit through these episodes—and/or read the book—and you will fill many if not most of the gaps in your “well rounded” education. You may even round it out a little, or a lot, further.

[Don’t miss the comment, below!]

Copyright 2014, Rubén Verdés (speedreaders.info).

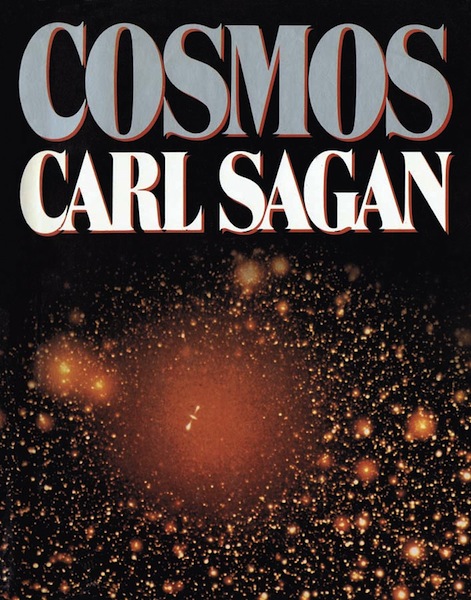

Cosmos 1st edition

by Carl Sagan

Random House, Hardcover – October 12, 1980

ISBN 0394502949

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

This review was more than a review for me. As I reflect, Cosmos has had an enormous impact on me and my children. For me, Cosmos was a touchstone—a work that heightened what I always viscerally thought science should be; an immensely relevant part of not only our intellect, but our humanity as well.

When I was a boy, men were first landing on the moon. That impact cannot be overstated—and I feel sure that for boys at that time… just like me, where they dreamt of being a policeman or a fireman before, now astronaut was added to that list. It was real. Growing up in the space age, America truly was a place where kids witnessing the unfolding of the unimaginable believed that any frontier could be conquered. Many adults felt the same way, and the ones that didn’t still believed it if only cynically; witness the popular saying/critique of that time for anything that failed: “we can land a man on the moon, but we can’t: _________.” Nobody uses that expression anymore!

Moon landings had ended in the early 1970s, and despite the Viking landings on Mars and the epic new journey the two Voyager spacecraft were undertaking, without a continued growth in manned exploration, the flirtation with growing up to be an astronaut faded, as the remaining astronauts were a small group destined to fly the Space Shuttle: a low earth-orbiting vehicle. There were to be no “Star Trek” adventures. An entire generation of disillusioned would-be “rocket scientists” saw no career path there and got MBAs or became lawyers instead. Enter Cosmos. In all that it did, it also helped keep that spark lit… the spark that was lit in the space age… the curiosity, optimism and “can-do” spirit that is inseparable from the narrative that Cosmos follows; as is glimpsed in the review above.

Interestingly, there is something about Sagan’s voice and manner of speaking that attracted my children to listen to him—and mimic him… while still in diapers. And, in doing so, they were learning. One “byproduct” was that many years later my son won “The Science Medal” awarded to the highest grade on a competitive science exam administered to his entire school, regardless of grade level. He told me that he was confident that he beat his upper and lower classmen because he knew things that came up in the exam because he had learned them from watching Cosmos! Yet, years before this, my son and daughter would routinely and repeatedly watch Cosmos with me and it sparked endless and interesting conversations. At that time, this aspect—this manifestation was so pronounced that I felt obligated to write a letter to Carl Sagan to thank him. After all, how can you see someone’s work be so influential to your children in such a positive way and not offer thanks? So I wrote Mr. Sagan a letter. And he replied. It began: “I want to thank you for your thoughtful and extremely generous letter.” My children were completely floored. Until that moment, they didn’t believe a letter so written would be replied to. The joy it caused them made me doubly grateful that he wrote the letter. That appreciation was particularly poignant when I learned how sick he was, and he still made a point of responding. He died just a year and a half later.

Now I come full circle back to the review. Shortly after Cosmos premiered, my cousin Andrew got the book and about a year later, he lent it to me. In early 1983, Andrew died of meningitis—he was only 16. Even now, a day scarcely goes by that I don’t think of him, and I have visited him many times in my dreams. The copy he gave me is one of my prized possessions… I can’t see it or hold it without seeing his face. I am proud and pleased to say that the cover of that very book is the one used at the top of this review. And I dedicate this review to him.

RV

I am Lorena Black.

The daughter so fondly spoken of by my father, the author of this review.

I cannot express the gratitude I have for Mr. Sagan all he has shown me throughout my life. I was only around 6 years old when he passed, but Sagan’s thirst for not only knowledge but the act of spreading it has watered the flower of my mind regardless of his presence. Cosmos is not just a series based on fact but theory, and shows us that theory—the art of wonder—has as much a standing in science as the atom. Sagan showed me the truths that lie before me in the night sky and the truth in the questions we ask. He showed me how the journey into science, the hypothetical—the concrete—the simple—the complex—are all justified reasons in pursing the experimental process. I did not get to meet my father’s cousin but he has always spoken of him fondly. I am happy that he birthed his love for Cosmos and Carl Sagan, because the magic of knowledge was what Sagan showed me. How the beautiful and whimsical is right above us—dancing in the heavens. We just have to look up and dream. For as dreamers, we are scientists–historians—mathematians…there is a fine line between all that is, will be, and ought to be.

I love you Dad.