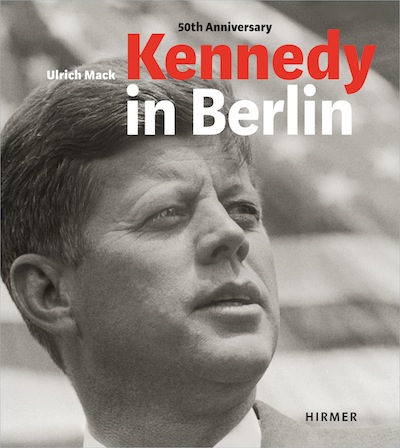

Kennedy in Berlin

There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the communist world. Let them come to Berlin … There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin … And there are even a few who say that it’s true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Lasst sie nach Berlin kommen—let them come to Berlin!

— John F. Kennedy

Most Americans of a certain age will know where they were when President John F. Kennedy died. Most Germans, certainly most Berliners, will know where they were when JFK was in their town. These events were just a few months apart and each left an indelible mark on history.

This book came out fifty years to the month, June 1963. Many people seem to have forgotten many things: that stop in West Berlin was only one on a four-day tour of Germany; JFK was extraordinarily ambiguous about Germany, both because of its checkered past and also its uncertain future on the knife’s edge of the Cold War—and that he had been there three times before (1937, 1939, 1945).

What people do remember is that immortal proclamation: I am a Berliner. Fifty years later they bring tears to my eyes still. I remember the roar of the crowd when the words had sunk in. The gap then seemed much longer than the almost instantaneous reaction that comes across in the news footage. This October marks the 25th anniversary of the Berlin Wall coming down; to thinking folk anywhere, “I am a Berliner” is shorthand for nothing less than the value and quality of life. JFK himself is said to have “left for his successor the recommendation: If ever you get discouraged, ‘go to Germany, go to Berlin!’ That, he assured, would help.”

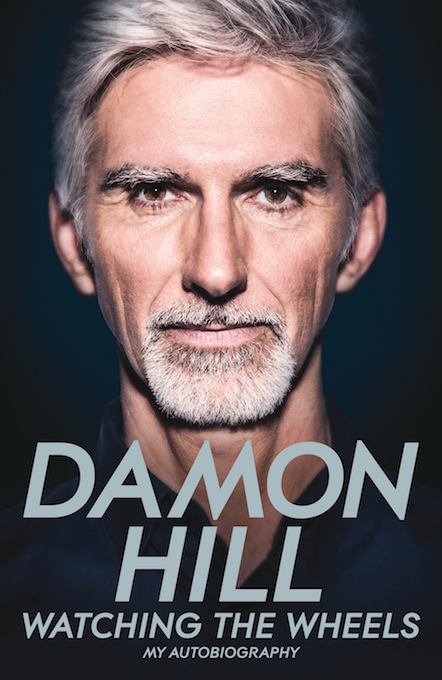

The fellow whose photos are featured in this book—many for the first time!—was also there, young Ulrich Mack (b. 1934), fresh out of art school and on his first magazine assignment. He would go on to become one of the very big names in photojournalism (also Artist in Residence at Boston U. 1995, 97, 99).

Mack had studied painting and photography under two names that also were rather big in German arts and academia. He certainly had demonstrated to them that he had talent and drive and the beginnings of a specific artistic vision—but it really does not help when one of the commentators in this book, Hans-Michael Koetzle, someone who specializes in the history and esthetics of photography, insists on saying—in the context of the Kennedy assignment—that “Mack was one of the highest-profile reporters of the 1960s. Many considered him one of the best German photojournalists.” That was all still to come (only a year later he garnered international acclaim for a photo essay on wild horses in Kenya) but to imply that Mack was the Big Man at the time his employer assigned him on short notice to the Kennedy press pool needlessly and misleadingly seeks to imbue the work with attributes that it has either not yet earned or that have not yet been ascribed to it.

The photos here are, in and of and by themselves, perfectly strong and well-conceived and -executed examples of intelligent photojournalism. Mack does know how to anticipate, where to stand, where to look, he sees the proverbial Kodak moment emerging and is ready in time to record it. “There is always a best place to stand, you simply have to know where it is.” He does know when a close-up and when a panoramic view works best. He is a storyteller, not just a photo snapper, even already then. In his own words, he thinks of himself as a craftsman not an artist, by which he probably means that he does not introduce artifice into his shots. The moment is what the moment is, unstaged, unmanipulated: honest. He considered photojournalism his “gift to history.”

In a way, this book is two in one: Mack’s 120 photos, and three essays exploring political and photographical themes. The photos are in chronological order of the five stops on the tour: Cologne, Bonn, Hanau, Frankfurt (and Wiesbaden), and West Berlin. Each section is introduced with a timeline of the itinerary; the photos themselves are uncaptioned.

To create context for the reader, German parliamentatrian and federal minister Egon Bahr who was a key figure in lessening tensions between not only East and West Germany but also Germany and the Soviets provided a very nice introductory essay. It is brief but forceful and cannot fail to impress upon the reader how very, very precarious the time was. At the end of the book, one essay by the aforementioned Koetzle speaks to the same themes but is mainly focused on Mack’s place in culture and society, and another by Jasper von Altenbockum connects the Kennedy visit and its meaning to US–German relations to subsequent visits by other US Presidents.

If it hadn’t become so entrenched in popular culture—even news maven CNN is guilty of mindlessly, ignorantly perpetuating the falsehood—it would be entirely frivolous to devote ink to this: “I am a Berliner” does not mean, in Berlin, “I am a jelly donut.” The idiots who flog this idea only show that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. Now, in West Germany, that’s a different matter and Berliners are, in fact, jelly donuts. But in Berlin, jelly donuts are Pfannkuchen. Trust me, I’ve had hundreds. And in Berlin you can get a baked good that you will not find anywhere else in Germany: an American! (In my day there were white and black Americans, even half and half; way too politically incorrect these days . . .

To return to the book: Mack selected the photos for this book himself. They will get under your skin, if you are so disposed. Take the time to really look. People’s expressions, human interactions, body language. It helps to have been there, or to have had direct experience of anything related to the palpable tension of the “Duck and Cover” Cold War era. If you have a bunker under your house, read the book there!

For the money, this book is a steal. Also available as a €300 limited collector’s edition of 99 copies but only directly from the publisher (ISBN 978-3-7774-2072-1).

Copyright 2014, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter