Audubon

My dear friend Keith, a scholar, is a methodical reader. In his small personal library, many books crowding the shelves he had constructed himself, he will sit in comfort in his overstuffed chair, twilight aslant in the room’s one window, and read the current book from his current schedule. Once he announced that he was going to read, in order, all of Thomas Hardy’s novels. My first thought was to wonder if he were well supplied with antidepressants—but different strokes and all of that. I, on the other hand, choose my books serendipitously. If I had not spied it at the local library’s discard bin and paid my quarter, I doubt if I would have ever read Constance Rourke’s account of the fabled naturalist, the beloved avian artist John James Audubon (1785–1851).

As I was about thirty pages into the biography and contemplated writing a Speedreaders review, I intended to focus on the idea that juvenile literature in the

1930s demanded more from a young reader than such literature would demand from today’s youth. The vocabulary—“reticent,” “gauge distances,” “animosities,” “savory,” and “inveterate reader” being but a few examples—is quite strong, and, too, I thought that today’s youngsters might be surprised and amused to find the older use of the word “gay”—as in “gay little parroquets” and “they were gay in their blue shirts, red caps, bright sashes.” (Please note: This is not intended to be in any way a  homophobic or prejudicial observation. In the main, youth today, thankfully, mercifully, would exhibit much more acceptance than that of their 1930s counterparts.) But as I read more of the book, I found that my assumption was incorrect, that the book had been intended for an adult audience (although it was a 1937 runner-up for the Newbery Prize for best contribution to American children’s literature), and my so my research was set on a different path. One negative criticism of the book, along with its 1930s paradoxical, well-meaning insensitivity to Native Americans and African-Americans, is its certain lack of sophistication, an almost adolescent telling of the tale.

homophobic or prejudicial observation. In the main, youth today, thankfully, mercifully, would exhibit much more acceptance than that of their 1930s counterparts.) But as I read more of the book, I found that my assumption was incorrect, that the book had been intended for an adult audience (although it was a 1937 runner-up for the Newbery Prize for best contribution to American children’s literature), and my so my research was set on a different path. One negative criticism of the book, along with its 1930s paradoxical, well-meaning insensitivity to Native Americans and African-Americans, is its certain lack of sophistication, an almost adolescent telling of the tale.

The tale itself is wonderful. From the vagaries of Audubon’s birth, through his triumphs and setbacks, his love of the wild, unexplored America, his friendship with Daniel Boone and William Clark, his honest love and affection for his wife and children, his dashing adventures, his fine, unwavering dedication to his art and his ultimate success offer to even a casual reader hours of satisfaction and escape. It is evident that Rourke was entirely familiar with Audubon’s journals, his artwork, his publications and, also, the opinions and chronicles of the artist’s contemporaries. As Rourke (a Vassar graduate, class of 1907, where she then taught English Lit for five years and pioneered the study of American culture) had also written a biography of Davy Crockett and a study of American humor, the historical milieu of the book rings true. For those with a more serious interest in Audubon, this book would serve well as an introduction, but it would be smart to follow up with later biographies, those by Richard Rhodes and William Souder among them. Research through time deepens and corrects itself.

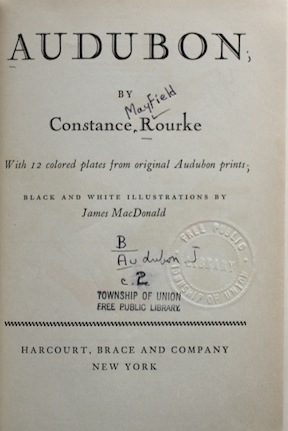

All of this is well and good, but Speedreaders often likes to focus on the book as a physical objet d’art, a cultural artifact, and Rourke’s book lends itself to this. There is a slight problem in this particular case, as the copy I acquired had been rebound; therefore I am missing the original hard cover and the book’s dust jacket. Some bibliophiles may cringe at such an example, especially a library copy, with, as the advertisements say, the “usual library markings.” Personally I find such markings intriguing and not unattractive; I particularly like, on the title page, the raised circular design created by the use of The Union Free Public Library’s handheld embossing tool. It brings to mind the warm atmosphere of a small town library, the librarians, perhaps overworked but generally content with the job, embossing, stamping, hand-printing the author’s middle name. It is a page that the artist Saul Steinberg would have understood.

All of this is well and good, but Speedreaders often likes to focus on the book as a physical objet d’art, a cultural artifact, and Rourke’s book lends itself to this. There is a slight problem in this particular case, as the copy I acquired had been rebound; therefore I am missing the original hard cover and the book’s dust jacket. Some bibliophiles may cringe at such an example, especially a library copy, with, as the advertisements say, the “usual library markings.” Personally I find such markings intriguing and not unattractive; I particularly like, on the title page, the raised circular design created by the use of The Union Free Public Library’s handheld embossing tool. It brings to mind the warm atmosphere of a small town library, the librarians, perhaps overworked but generally content with the job, embossing, stamping, hand-printing the author’s middle name. It is a page that the artist Saul Steinberg would have understood.

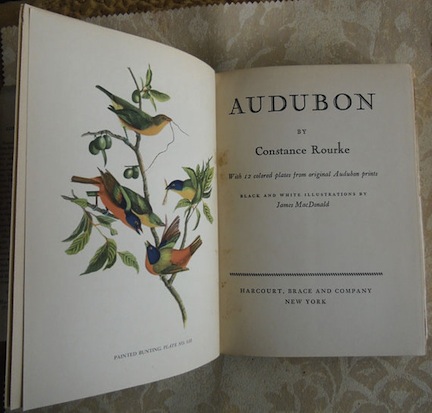

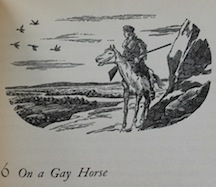

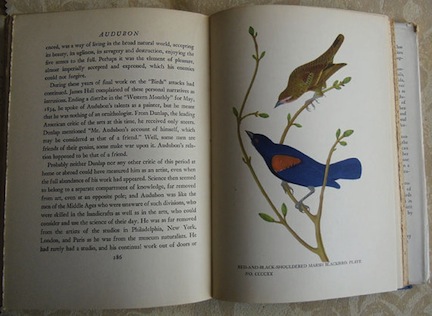

Apart from the lack of the original cover, my 1936 copy is in excellent shape—and as only one date is listed, I am assuming a first printing, if not a first edition. The chosen font, not identified, is easy on the eye. The James MacDonald black-and-white illustrations, showing vignettes of wildlife or of Audubon himself, remain crisp, and the twelve colored Audubon plates, found throughout the book, are bright, the colors still vivid and clear. These are printed on paper with a slight gloss, and the back of each is blank. Audubon has a six-page Index and fourteen pages of Notes. Here Rourke makes the appropriate acknowledgements, discusses her sources and, at the end, discusses the—now debunked—theory that Audubon had actually been the son of Louis XVI. Apparently this was in the way of an early urban legend; if you recall your Huckleberry Finn, one of the confidence men Jim and Huck encounter claims to be the long lost, presumed dead Dauphine. Overall—a book easy to recommend.

In our world of etailing, copies of Rourke’s Audubon are everywhere. Perhaps your copy will be mint—with a clean dust jacket, pure white pages and brilliant plates. One can but hope.

In our world of etailing, copies of Rourke’s Audubon are everywhere. Perhaps your copy will be mint—with a clean dust jacket, pure white pages and brilliant plates. One can but hope.

Copyright 2015, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter