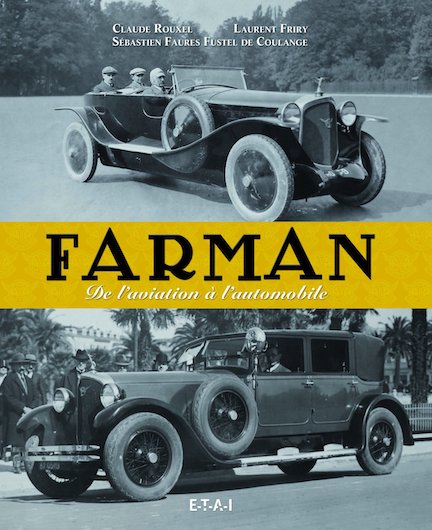

Farman: De l’Aviation á l’Automobile

by Claude Rouxel, Laurent Friry

by Claude Rouxel, Laurent Friry

(French) Why buy this book? Who cares about Farman? Of the total production of some 450 cars, only five survive, of which a lonesome pair has avoided museum incarceration. The name lacks the cachet of the marque’s French and Italian rivals, with their sexy double-barrelled amphibrachs; to English speakers, it sounds more agricultural than exotic. Competition successes were there none. So why would such three such talented authorities as Friry, Rouxel and Faurès labor for so long to produce the definitive work (for it will never be bettered) on such an obscure make?

None of these questions would have made sense at the legendary “Salon des 40CV” in 1919, where the Farman A6 made its début alongside similarly ambitious offerings from Delaunay-Belleville, Renault, and the aviation-spawned creations of René Fonck, Gnome & Rhône, Voisin and Hispano-Suiza, because Farman was then one of the most famous names in the world. This was mainly thanks to the middle of the three brothers, Henry. Having competed with distinction on two wheels and four and in powerboats since the turn of the century, his feats as a pioneer aeronaut from 1907 onwards—being the first in the world to fly from one town to another, for example, and a succession of distance, speed and altitude records—hit the headlines from Archangel to Los Angeles. He was even nominated for a Nobel Prize. And the thousands of Maurice Farman and Henry Farman aircraft that had recently supported the Allied war effort (not least in the RAF, where they were affectionately dubbed “Horace Farmans”) were the swords that were turned into the ploughshares of civil aviation in the Vintage years.

Well known from bookshop shelves as well as newspaper headlines, the name had the burnish of glamor, which the brothers put to good use in their cars. Overachievers all three, they did nothing by halves. With a vast, superbly equipped factory and a highly skilled workforce in the industrial suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt, they set out to make the best car they could, with scant attention to cost. The result added a reassuringly excessive specification to the magic of the name, and attracted a constellation of plutocrats, war heroes, titled families and stars of stage and screen, notwithstanding a price tag 25% higher than a Silver Ghost’s. It was France’s Duesenberg.

This much you may know, and it sounds a simple enough tale. It is not. Nothing about Farman is simple, not least their products. And it is the genius of this book to have unravelled the labyrinthine complexities of this vast subject enough for the general reader to get a sense of the main players, the trajectory and influence of their tangled business interests, and the evolution of their strikingly distinctive machines. What other car do you know with a barometer and gradient meter as standard equipment, let alone double steering and twin dynamos?

Years of original research have yielded an account crammed with stuff you never knew. Here for the first time, for example, is the full story of the hitherto shadowy figure of the firm’s chief engineer Charles Waseige—the fourth of the Farman musketeers, who was responsible for the aero engines as well as the cars. Beginning as a draughtsman with Clément, Waseige hitched his star to the great Marius Barbarou, whom he followed to Benz, Adler and Delaunay-Belleville, whence he was poached in 1914 by Fernand Charron for Alba, his joint venture with the Farmans, where Waseige penned the new marque’s Grand Prix entry. Postwar, it was Waseige who designed Farman’s first 4-valve V8 aero engine and its many successors; given carte blanche for the A6, he designed a 6.6L ohc six similar to Birkigt’s unit for the H6 (although they were concurrent). Agricultural they were emphatically not.

Readers may recognize Faurès’ voice in the limpid analysis of Farman engines, and the way the original A6, with its cone clutch, separate gearbox and problematic rear axle location, evolved into the firm’s fiendishly complex New Farman swansong of the early 1930s. Rouxel makes a fine job of shaping the equally convoluted narrative, and Friry casts an expert eye over the soberly classical coachwork that adorned most of these exotic chassis—much of it made in-house, including the low-slung and dramatically avant garde Supersports.

The authors include other Farman products, including the Hydroglisseurs (aerofoil-supported hulls propelled by an aero engine at the stern) that introduced new perils to French inland waterways. The de Luxe version was a glorious folly reminiscent of a waterborne Pullman coach, but this reviewer lusts after the tiny Passe-Partout, a canoe hull with an aft-mounted, afterthought, airscrew. At the other extreme, in 1924 a Farman hull powered by a 450 hp W12 Lorraine-Dietrich aero engine took the world water speed record at just over 450 kph.

Waseige’s postwar aero engines for civil use were notably reliable, with a Rateau turbo blower giving excellent high altitude performance. At the same time as the launch of the technically fascinating New Farman car, a new range of inverted engines introduced the W18 format (with three banks of six), but their undoubted aerodynamic and installation benefits nevertheless failed to dethrone Hispano. Waseige’s lasting contribution to aviation was the light and robust bevel gear epicyclic propeller reduction drive known as a Farman Drive, which was adopted by Bristol and Pratt and Whitney among others.

The photographs are superb. Even if you don’t read French (a pity, because the style does justice to its subject), this book is worth the asking price for the pictures alone. Period shots, whether posed for publicity purposes at the factory, by coachbuilders or at concours, leavened by informal family snaps and extracts from brochures and other ephemera, all immaculately reproduced on high quality paper in a layout that shows pleasing attention to detail. This is a labor of love.

Bloopers? A couple, but so inconsequential as to be not worth the ink. It doesn’t pretend to be a comprehensive chronicle of the Farmans’ long careers, since that would occupy several volumes—but from the championship bicycle racing and ballooning exploits and little-known early adventures such as the Farman et Micot cars, it explains everything you ever wanted to know about Farman, and then some. Built to last for ever, Farman cars fell victim to their complexity and the value of the raw materials from which they were made. As the first serious study of the marque, there’s every reason to believe this fascinating and long-awaited book will outlast its subject. Brilliant.

Copyright 2020, Reg Winstone (speedreaders.info)

This review appears courtesy of the British magazine The Automobile to which Winstone is a contributor.

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter