Maserati 5000 GT: A Significant Automobile

by Maurice Khawam

by Maurice Khawam

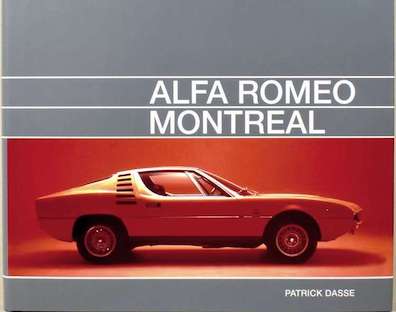

Unlike the voluminous literature on Maserati’s racing cars, the firm’s touring cars are most often relegated to a mere chapter in the multi-model marque histories. Author Khawam makes the case that the 5000 GT is such a significant car in terms of engineering and design that it deserves a stand-alone book—and set out to write it since none existed. As long as the model designation “5000” is still fresh in your mind, realize that only 5000 copies, individually numbered, of this book exist. (Good thing Khawam didn’t use the type designation the factory assigned: “103”!) In historical terms the car does have several notable attributes: it was the firm’s first V8-engined road car, the first fuel-injected car in Europe, and the fastest and most expensive production car of its day.

Built for only a few years (1959–1964) and in miniscule numbers (34), the 5000 GT came at a precarious time for Maserati, following the firm’s bankruptcy in 1958 as a result of failing to win the 1957 World Sportscar Championship and thus unable to pocket expected income. The book explains all this in satisfying detail, beginning by setting the scene with a technical description and brief competition history of the V8-engined Maserati racecars and a summary of the economic realities that forced the cancellation of the racing program—and the resultant surplus of V8 motors.

Little—too little—is said about the successful 3500 GT model other than making the obvious point that its beefed-up chassis became the basis for the 5000 GT. While the idea of shoehorning a V8 into a 3500 GT is always, and plausibly, attributed to the Shah of Persia (now Iran), one should think that Maserati would have hit upon that solution for repurposing their stockpile of leftover racing engines themselves sooner or later. Be that as it may, the first 5000 GT—intended, in fact, as a one-off—was his. History didn’t record his reaction to other well-heeled clients liking it so well that Maserati ended up building another 33 (35, if you count the two remanufactured cars).

The book presents the whole design and development history along with technical specs. Aside from minor mechanical differences it is the custom coachwork by eight different stylists that distinguishes these cars from each other and also from other cars of the time. It is on this subject that the book advances the body of knowledge the most. Based on a thorough examination of factory records and correspondence with owners the author is able to describe each and every chassis in great detail and suitably illustrated. Throughout, most of the photos are not identified by chassis number and a reader with very specific interests would do well to start with Table 3 which lists all 36 cars by chassis number, body and date along with various other data points and is followed by several pages of notes cross-referenced to table entries.

Many of the period photos came from Maserati’s as well as various racing archives, and the multi-faceted David Gooley handled modern-day set-up photography. They are augmented by reproductions of several pages of the handbook, a few technical drawings, graphs, and tables of race results for the types 450 S, 151, and 65 (Maserati expert Wilhelm Oosthoek had his eye on these).

Another key feature of the book is a comparative design analysis of each of the eight coachbuilders by the American designer Tom Tjaarda (Innocenti 1100 Ghia Coupe, Fiat 124 Spider, Ferrari 330GT 2+2 and 365 GT California Spider, DeTomaso Deauville and Pantera). Before reading it readers should page ahead to the two pages of color drawings in profile by graphic artist Stan Foster because seeing all eight body styles at once will help in understanding Tjaarda’s commentary. Tjaarda is eminently qualified to render such a critique. He not only worked for several Italian coachbuilders himself at just that time but was Ghia’s head of design from 1968–1977.

Comments about 13 cars by their seven current owners and a discussion of the other V8-powered production Maseratis and concept cars up to the present day round out the book. Appended are a graphic representation of the 5000 GT family tree and, very clever, a map of the world indicating the trade winds and race tracks after which Maseratis are named. Also of note, the Forewords are by Adolfo Orsi, Jr. (son of Omar Orsi who became managing director in 1937) and Giulio Alfieri (d. 2002) who as chief engineer was a key figure in the development of racing and production cars in the 1950s and 1960s.

It is really quite remarkable for a private enthusiast to have undertaken a project as ambitious as this. Khawam, who is an aerospace engineer and published author in his field and manages a technology company, took three years out of an already full life to not only research and write the book but also publish it himself. This is what happens when as an impressionable lad of 12 you see a neighbor’s 5000 GT every day “parting traffic like Moses the Red Sea!” Hardly anyone gets rich publishing niche books like this; they are a labor of love and the world is the better for it.

Copyright 2010, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Sabu,

I like the review, thanks. It sure expands on what Steve did. Just keep in mind that there were 34 cars made and 2 remanufactured.

Finally, please give Moss my regards and tell him that I would like to present him with a signed copy of my book.

Best, Maurice