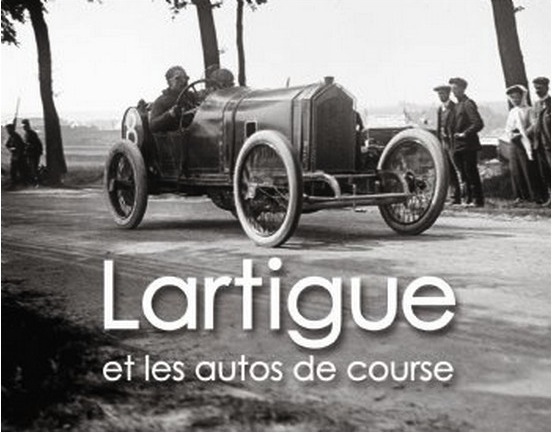

Lartigue et les Autos de Course

by Pierre Darmendrail & Christophe Lavielle

by Pierre Darmendrail & Christophe Lavielle

“I run after anything that awakens my enthusiasm—whether it be a poppy field, a car, an aeroplane or a demonstration of human genius.”

—J.H. Lartigue

(French/English) Lartigue was 91 when he said that—and photography still excited him!

This book is interesting on so many more levels than just the obvious, that being auto racing. Whether it is the actual cars or the “moment in time” aspect of documentary period photography, or photographic technique itself, the voluminous output of French photographer and painter Jacques Henri Lartigue can be approached from many different directions. Both the sheer quantity and also the originality of his work exceed any parameters of “normalcy.”

To appreciate just how extremely visual—and sense-oriented in general—a person Lartigue (1894–1986) was, consider that as a child he invented a game for himself: fix your eyes upon something, open wide, spin around, close eyes, SNAP—the image, or sound or sensation is now imprinted upon your mind, nevermore to be forgotten, and will save you from “ever being bored or sad.”

Cheap thrills, yes, but more than that it shows an uncommonly acute sense, certainly for a child, of the fleetingness of time. Over the course of his life this drove him to take many thousands of photos, over 100,000, including some 5,000 stereoscopic ones. Not only that, he took the precaution of also sketching what he had photographed, from memory, at the end of the day, before he developed the film lest the image should be lost during the chemical treatment. Aside from that he created more than 1,500 paintings and 7,000 diary pages. Sure, in time, what he produced found commercial application and value but, at the core, he did it because he couldn’t not do it. Even at the age of 80 he wondered, at the 1978 Monaco GP (here shown in the Epilogue), “It’s hard to imagine that the photos I take will become intriguing historical documents.” But they are.

Lartigue takes in the world around him with a hyper acuity that seems almost indiscriminate. His diary entries devote as much detail to the hats everyone wore in the carriage and the smell of its sun-warmed leather bench as to the cars and drivers at the 1905 Gordon Bennett Cup, the first race he attended, 11 years old. By that age he is already a “seasoned” shutterbug, having received his first camera three years earlier and several new ones since, courtesy of monsieur papa whose hobby it is. Surely by now, dear reader, it must be clear that this boy is different from you and me. “And then, without warning, voumff!, the car had gone past, and I hadn’t taken the photograph! I hadn’t even seen the car properly! Dad said ‘Don’t worry, there will be more coming along’ . . .”

These very photos are shown here. And next year’s. And then we skip a few years and see a few more races and then skip a decade and see a few more. And so it goes; we almost grow up with Jacques Henri.

The first 30-odd pages attempt to “explain” that precocious youth; much use is made of diary entries to let him speak in his own voice. He is put into the context of his time, rife with technical wizardry on all fronts. We meet the family into which he was born and the one he himself started in 1919, automobiles imagined and real, observed and owned. The book’s focus is predominantly on the photos plus drawings related to them but does not touch upon the paintings that after 1915 become and remain Lartigue’s main professional activity, meager as it is. If all this makes, as it should, the reader curious to learn more, realize that this is not the book for it. There are many others, about him and his work, even one by himself. The deepest insights come from his peers—but try finding those! It is, for instance, in the preface to a catalog of a Japanese exhibition of Lartigue’s work that his great champion and friend, famed US fashion photographer Richard Avedon who was so instrumental in bringing public attention to Lartigue’s post-1930 photographs by publishing Diary of a Century in 1970, where he writes, “Lartigue never exhibited his pictures until 1962. He never thought of himself as a photographer. It was just something he did every day . . . every day for seventy years. Out of love of it. And every day his eye refined and his skill with a camera grew. He was an amateur . . . never burdened by ambition or the need to be a serious person” and then labors to convey the man’s utter genius. Here is a key observation, even if it is not really applicable to these car photos: “The photographs imply things that happened before and after they were taken.” Think about that!

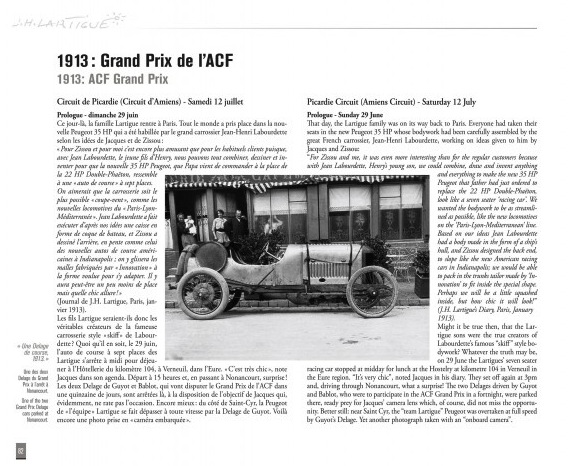

In this book you’ll have to discover that genius largely by yourself. This is not a deficiency or oversight, it is simply not this book’s primary purpose or intention. And those who take their time and have eyes to see will see. Newcomers to vintage photography will love the final of the introductory sections, “The Mona Lisa,” the famous 1913 photo (left) in which everything looks cartoonishly askew. What looks like trick photography or a mistake is neither, although Lartigue himself for decades considered it weak. Learned books could be, and of course have been, written about the technical aspects of shutter mechanics (scrolling top to bottom in this case) and film speed and kinetics and the photog leaning into the shot, and it’s all very well explained here. The authors also explain why and how this photo that was for so long misdated and -captioned came to be correctly identified.

The bulk of the book presents some 20 races/seasons (along with two years of peripheral/personal material and two racing movie locations Lartigue visited) in mostly full-page, thoroughly captioned, supremely well-reproduced b/w photos (only 1978 Monaco is in color), many not previously published. Each event is introduced with a page or two of commentary and quotes and the occasional facsimile of a diary page or race brochure.

A note to US readers: there are a few references to dimensions but without unit of measure; they are obviously metric. The publisher (the European partner/distributor of US publisher Racemaker who in turn is the sole US source for this book) has quite a number of such books and they are all delectable. Each author has published other racing books.

If you’ve never heard of Lartigue you don’t know what you’re missing! If you have the 1974/1998 book J.H. Lartigue, les autos/et autres engins roulants (ISBN 978-2851080257) you’ll still want this one because it’s just . . . Better. More. Prettier. Smarter.

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Next time you watch the movie The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou look for the portrait of Lord Mandrake—that’s Lartigue! And “Zissou” is the nickname of his older brother Maurice. Director Wes Anderson is such a fan that he based a shot in his much earlier movie Rushmore on one of his photos.