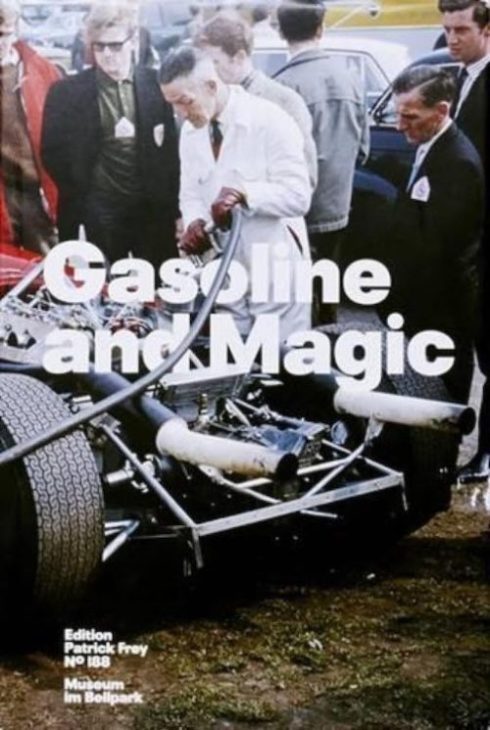

The Formula

How Rogues, Geniuses, and Speed Freaks Reengineered F1 into the World’s Fastest-Growing Sport

by Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg

by Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg

“It’s a business where the rules change constantly and even people with PhDs in aerospace engineering can’t always figure them out. If soccer became the world’s most popular sport because it requires no translation, then F1 is the opposite. Making sense of it can seem like it requires graduate-level physics. Most of the people competing in it fail to grasp all of the intricacies all of the time.”

With some books, you drop everything, rip off the shrink wrap, and start reading until your eyeballs cry foul. This was not one of those. At least it didn’t start that way.

When it arrived, it went to the bottom of the pile of new books, to await its turn. That subtitle didn’t help. Although admirably detailed it seemed just too contrived. How Rogues, Geniuses, and Speed Freaks Reengineered F1 into the World’s Fastest-Growing Sport. Oh my.

Turns out the authors’ previous two sports books, on soccer, have similarly elaborate titles so that must be their thing. Then there’s the fact that neither of them is a motorsports specialist, although it does say The Wall Street Journal on their business cards—Robinson is the European sports correspondent and Clegg an editor. How to calibrate one’s expectations? F1 is too complex a beast to lend itself to deep analysis by people on the periphery who just dip a toe into the subject matter. Would this become yet another reason to mourn the loss of the trees that were felled to provide the paper for a book no one needs? Will I waste hours of my life that I will never get back?

Well, I invested hours of my life into writing a review so there must be an upside.

In many aspects, The Formula falls in with such books as The Piranha Club (Timothy Collings, 2001), The Powerbrokers (Alan Henry, 2003), Bernie’s Game (Terry Lovell, 2003), Formula One: Made In Britain (Clive Couldwell, 2003), Driven: The Men Who Made Formula One (Kevin Eason, 2018) or Formula One (Anthony Pritchard, 1966), Grand Prix Year (Ted Simon, 1972), Fast and Furious (Richard Garrett, 1969). One common denominator is that they tout the wonderfulness, the magnificence, the greatness, and the sheer brilliance of Formula One. Most originate from that former part of Europe across from the Continental coastline, Air Strip One, better known as the United Kingdom. In other words, books that postulate that without the Pommies, there would be no Formula One. Sorry about that, France, Italy, Germany. He who writes the books shapes the narrative.

The Formula takes a different tack to explain how F1 got to where it is today. There are books I classify as Nice Tales Worth Reading; on the factual end they are not necessarily pinnacles of groundbreaking research, nor are they top-shelf examples of fabulous writing, but they do have enough merit to move the needle. The Formula fits into this category. Yes, there are instances of clankers that make the historian in me groan and engage in obligatory eye-rolling but they pertain to matters of nuance in regards to background and context and don’t weaken the overall effort.

My experience with Grand Prix racing dates back to June 1954, when at the ripe old age of seven I attended the Grand Prix de Belgique at the Spa-Francorchamps circuit. A decade earlier, my father had first seen the grandstands when his unit was in the area during the opening hours of what would later become known as The Battle of the Bulge. That 1954 race weekend also happened to be when the movie the The Racers was being filmed there. If you know when not to blink, I’m in one of the crowd scenes for a nanosecond. Driving his last race for Officine Alfieri Maserati in what is now an iconic Tipo 250F/1 that weekend before Mercedes made its debut the following month in France, Juan Fangio won the race. Back then, the series was known as the Championnat du Monde des Conducteurs.

In 1980, the Championnat du Monde des Conducteurs was abolished by the Fédération internationale de l’automobile (FIA) and beginning with the next season was replaced by the FIA F1 World Championship for Drivers (with a companion F1 World Championship for Conductors, replacing the former Coupe Internationale des Constructeurs). This was the culminating event of a clash between the FIA and the FOCA (Formula One Constructors Association), the latter led by a former used car dealer, a certain Bernie Ecclestone. [Here I must point out that Ecclestone DID NOT form FOCA, its origins dating back to early 1964, but he did change the name from F1CA to FOCA, for reasons perhaps obvious to those with juvenile minds . . . ]

It’s at that point in time that Robinson and Clegg begin their tale in earnest, and in a manner that makes the book worth taking the time to read. It is the commercial aspects of the series that singularly benefit from their experience at The Wall Street Journal. The conflict that resulted in the FIA and FOCA literally going to war from the latter-1970s until early 1981 was after all about money. The new F1 World Championship that began in 1981 was very different from its predecessor, which ran from 1950–1980, in that the commercial rights of the series were now owned by the FIA. Cut to a mental image of Joel Grey as the emcee in Cabaret singing “Money Makes the World Go Round . . .” and you have it.

The Robinson-Clegg take on how Ecclestone, followed by CVC, followed by US company Liberty Media (and others) conspired to make F1 a cash cow is easily the best by far that I have come across. The relentless hawking of F1 in recent years, after its greatness and wonderfulness had stumbled (more than) a bit under The Great Bernie as well as the mercenary, money-grabbing, back-stabbing antics of the modern F1 teams, and the efforts to finally (literally) sell and promote F1 in the United States makes for an antidote to the usual vapid, thought-free tripe that F1 flogs on its own website or that other F1 propaganda mills churn out. (Why do you think those sites do not report accurately on the rejection of GM-backed Andretti Cadillac for a place on the 2026 F1 grid? Also, ever wonder why most of the F1 teams are based in the United Kingdom despite several nominally being German, Austrian, American, French?)

Oh, various F1 scandals, controversies, and embarrassments do get the necessary attention and coverage. This is often from a different angle than one gets from the captive F1 press, many of whom appear quite happy to parrot the Party Line and kowtow to the New Men in Blazers (New Boss same as the Old Boss, as The Who would suggest, just a different blazer and level of incompetency) so as not to jeopardize the privilege of being invited to cover the sport.

After the monotony of Mercedes winning eight straight F1 constructor championships (2014–2021) the geniuses at F1 started rewriting the technical part of the rulebook, a document of enormous complexity. It’s supposedly exhaustive and definitely overdetailed (except when it isn’t—yet teams always seem to find loopholes or ambiguities).

Beginning in 1981, the Technical and Sporting Regulations were combined in a single rulebook. Previously there were the sporting regulations concerning the championship and a separate set of technical rules pertaining to the “formula” that was Formula 1. Not until the 1961 season was it mandated that a world championship must use cars conforming to the F1 technical specs; while the technical rules or the sporting rules might change, they were still separate sets of rules. This is how the 1952 and 1953 world championships were run using cars using the then current F2 specs, and the 500 mile race at Indianapolis was part of the world championship from 1950 to 1960. Plus, F1 as a set of technical regs was in existence well before 1950. This resulted in the current situation with the Red Bull team winning 21 of 23 events in 2023 and then 17 of 22 in 2022. Yawn City, as they used to say on The Boulevard.

All in all, The Formula is the sort of book that will give uncritical F1 fanboys palpitations because it tells it like it is, not like the propagandists say it is. Yes, Robinson and Clegg do give one a sense that they really are pretty impressed with the whole shebang, but not necessarily willing to take it at face value.

Despite my initial trepidations, I am glad I read the book. Time well spent!

Copyright 2024, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter