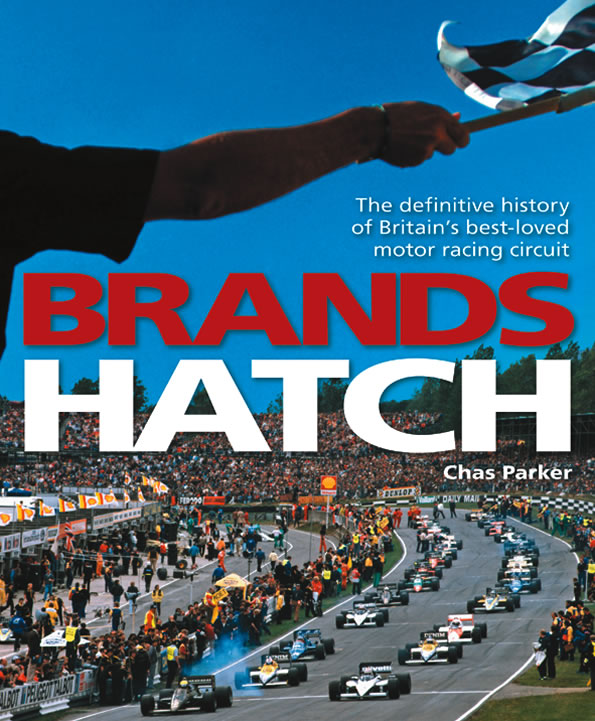

Brands Hatch: The Definitive History of Britain’s Best-Loved Motor Racing Circuit

by Chas Parker

by Chas Parker

In declaring to write the “definitive history” Parker set himself an ambitious target. Competition may have been sparse—Brands published several histories decades ago, and Parker himself was between writing (for Veloce Books) a pair of simple guidebooks to racing there in the 1970s and ‘80s when he published this work—but without question, he achieves his ambition.

One reason for the book’s success is its structure. Parker explains in his Introduction that race results and reports can be obtained from many sources; his story of Brands will be “as told by the people who worked and raced there.” He thus devotes a chapter to each decade, narrating the developments and painting the characters of that period in a pleasing, flowing style of writing, and concluding each chapter with bullet-pointed highlights from contemporary race meetings. The icing on the cake comes in the form of separate sections devoted to personalities giving their views on Brands, from Grand Prix giants like Moss and Clark to British touring car stars such as Plato and Priaulx.

Clark’s description is gripping, and demonstrates that Brands was never an easy ride: “. . . quite an undulation in the surface . . . sudden change in camber . . . quite a bit of G . . . curious sensation here on a grand prix car . . . a rough patch coming out . . . another ‘dip’ just across the line.”

F1 impressario Bernie Ecclestone is an interesting choice to write the Foreword, for it was he who, in 1986, abruptly ended the arrangement to alternate the British Grand Prix between Brands and Silverstone, which had existed for more than 20 years. Here, he endorses Parker’s claim that Brands is “the country’s best-loved circuit” but his use of the past tense in the very next sentence is telling—“In its heyday, it was the heart of motor sport in England and was always one of those nice places to go.”

Parker justifiably opens his account by introducing us immediately to John Webb, the sheepskin jacket-clad man whose name is synonymous with Brands. Webb first became involved as PR agent to the circuit, in January 1954. It was his idea to launch the famous Boxing Day meeting 12 months later; such an event may have been common in British horse racing at the time, but it certainly wasn’t in motorsport. 20,000 spectators turned up to enjoy a seven-race meeting, an ox-roast, and Stirling Moss dressed as Father Christmas! Webb, and Brands, were on their way.

Then we’re taken back to the mid-1920s, when the local farmer, with little use for such poor, chalk-based soil, readily let motorcyclists go grass track-racing there. Soon, the kidney-shaped track at the heart of today’s Indy Circuit became established, though at this time they raced around it in anti-clockwise direction. Incidentally, this gives some historical precedent for recent publicity by MSV, Brands’ current owners, whose posters have shown cars racing the “wrong” way up the pit straight!

The Army requisitioned the site as a transport depot during the Second World War, and inadvertently supported its rapid postwar recovery by leaving behind dozens of drums of gasoline, which fuelled the racing there through an austere period of rationing. The one-mile grass track was first surfaced in 1950, and the climb up, round and down Druids was added during the winter of 1953–54, extending the circuit to 1.24 miles, and presaging the switch to clockwise racing. The Grand Prix loop, which followed in 1960, extended the length of the circuit to 2.65 miles, and was made possible in the light of fierce opposition from local residents by it being laid out on the path of an old scrambles course, thereby complying with planning regulations.

Where Parker truly excels is in getting each of the several extremely strong personalities to have dominated the Brands Hatch landscape down the years to tell their stories. These sometimes conflict, and I understand the manuscript had to be approved by numerous lawyers before publication.

Webb’s position was consolidated in the early 1960s, when Grovewood Securities bought out more than 50 bickering shareholders, and he joined the board. He satisfied a long-term goal when Brands first hosted the British Grand Prix in 1964, and filled the gap in his budget the next year with the non-championship F1 Race of Champions. Two decades on, he and his small, focused team were able to lay on the Grand Prix of Europe in 10 weeks when the 1983 New York Grand Prix was cancelled, and they repeated the trick two years later when Rome pulled out of its commitment to host a race.

But that event, Brands’ fourth Grand Prix in as many years, marked the apogee of the circuit. Grovewood’s parent company was acquired, and was obliged to divest itself of its motor racing interests. Webb tried to arrange a management buy-out with finance from Ecclestone and Atlantic Computers’ founder and historic car racer John Foulston, but the deal went ahead without Ecclestone, who shortly afterwards signed an exclusive arrangement with Silverstone to host the British Grand Prix.

Though Ecclestone denies that this had anything to do with his not being a part of the deal to acquire Brands, Webb is clear: “According to Foulston, Bernie threw all the toys out of the pram when the deal was announced, and took the Grand Prix away from Brands Hatch.” Ironically, Ecclestone and Silverstone went on to endure a difficult relationship, and when asked if he regrets granting them an exclusive deal, he replies, “Absolutely. One hundred per cent. One million per cent. If we could have kept the race at Brands, that would have been, for me, the best thing that ever happened.”

The new management structure unravelled quickly when Foulston was killed testing a USAC McLaren at Silverstone and Webb found it impossible to work with the businessman’s daughter, Nicola. He left the circuit that had been his life for more than 30 years. He remarks scathingly, “From that moment on, Nicola methodically broke up what was probably the best team in British motor sport.”

Nicola Foulston comes across as an extraordinarily driven woman, ridding herself of 17 directors in 27 months and falling out with her own mother in pursuit of her goals. At one point, during convoluted negotiations to acquire Silverstone, she had a contract to host the British Grand Prix, without being in a practical position to run it on either track. She sold out to US marketing group Interpublic, who hadn’t taken the precaution of checking her contract of employment, and this enabled her to quit immediately.

Little more than four years later, Interpublic sold Brands and its sister circuits into the safe hands of Jonathan Palmer’s Motor Sport Vision, writing off a nine-figure sum in the process. One of Palmer’s first actions was to hire Webb as a consultant.

Parker may well be a passionate motorsport fan, and have contributed to Autosport and Motorsport News, but he handles the complex web of Brands’ ownership with such confidence that the reader could be forgiven for thinking he works for the Financial Times or Wall Street Journal.

There is just one minor flaw in the book. A quality work like this, focused on a single circuit should include plans drawn to a consistent scale to demonstrate the development of the track over time. Brands certainly demands this treatment since it went through so many stages: the development of the basic “kidney” (first one direction, then the other), the Druids extension, and the Grand Prix loop are only the most significant. But Parker’s Appendix contains just three plans, lifted from a ‘60s program, a 1999 Autosport article about Nicola Foulston’s aborted plans for a revised pit layout, and an up-to-date MSV publication.

The book is generously illustrated. The most striking shot is of Nicki Lauda, in his McLaren overalls, urinating in the paddock during the 1984 British Grand Prix meeting. The poorest is the composite cover image. There may have been days when the skies over Brands were as deep blue and as cloudless as depicted, but clearly not on the one when the cars lined up for the 1985 Grand Prix of Europe.

But don’t judge this book by its cover. Simply enjoy the superb work behind it.

Copyright 2011, Paul Kenny (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter