The Edwardian Rolls-Royce

With a dissertation on the pre-40/50 h.p. cars by Tom Clarke

With a dissertation on the pre-40/50 h.p. cars by Tom Clarke

by John Fasal and Bryan Goodman

Edwardian Rolls-Royce predominately refers to the 40/50 hp model commonly known as Silver Ghost, the car whose mechanical excellence made the company famous, making the words “Rolls-Royce” a byword for excellence in any endeavor. These books cover that formative era (including the cars that came before the 40/50) and in so doing have become nothing less than a landmark achievement, and now, a benchmark for anything that may come after.

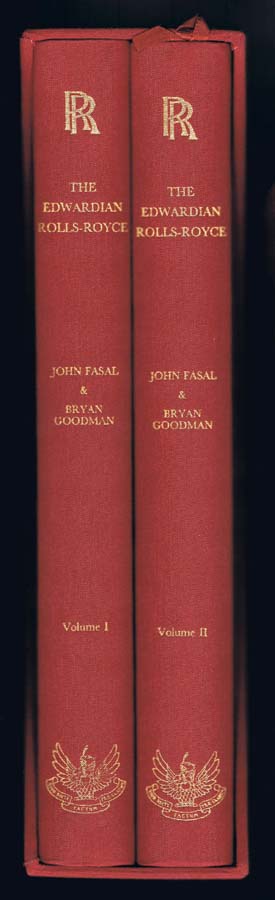

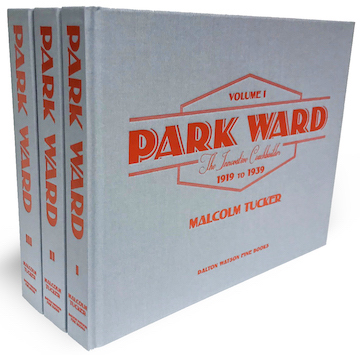

The two books are handsomely presented, gilt-edged and slipcased, and weigh in at 15 lb. And that’s just the red-cloth standard edition; there is also a premium version bound in dark brown leather with gilt Rolls-Royce logo on the front cover with raised bands to the spine and marbled endpapers. Judging the book by its cover raises lofty expectations as to what’s inside. Not to worry, it does not disappoint. The work covers Rolls-Royce motorcars of the Edwardian era (and a little beyond), dating from the first production in 1904 to 1917. Each car produced (and even those that were not actually completed but were assigned a chassis number) is listed within, one after another, including owner histories. Given the model’s supreme importance in the history of auto making and their uncommonly high survival rate, such a compendium is of immeasurable value to the historian, not to mention the lucky owners of these cars.

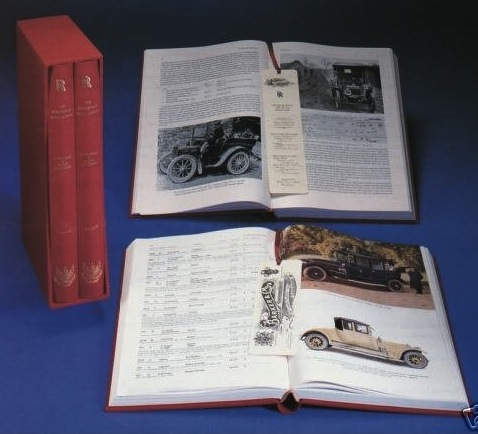

The presentation is spectacular. From the tactile feel of the premium glossy paper to the type, spacing and content, the data is literally beautiful and its detail is of commensurate beauty. The data is complemented by a breathtaking number of illustrations of the actual cars covered in the data, meaning that even the casual consumer of coffee-table books would find it appealing.

One is easily lured in by the presentation but soon realizes that this work is nothing less than a tour-de-force, from an extraordinary guide to the development of early automotive coachwork to a forensic work illustrating chassis development and covering production history with supporting references. To fully convey the vastness of the book’s scope and the eminence it has been accorded in the body of literature it is necessary to go into more detail than we normally do in describing contents, so lets walk through what’s inside:

Volume I (432 pages) goes up to page seventeen in Roman numerals to cover the following: a listing of color plates; acknowledgements (it is apparent that all the torchbearers, private and institutional, in the Rolls-Royce world were consulted); picture acknowledgments; a preface by the authors that explains their methodology in producing this work (clearly, no stone was left unturned. Consider this example: “Tying the photographs to owners and thus to chassis numbers was frequently only possible due to our good fortune in having the custodianship of the archive of three generations of the Francis family who painted most of the heraldic devices on the coachwork of these early cars. Their records include a sketch of every crest applied to a vehicle. Hours spent with a magnifying glass on coachbuilders’ photographs enabled many cars to be tied to their chassis number.”); the Foreword by Michael Vivian and Robin Barnard who themselves contributed input and archival material to this work gives the reader an appreciation of the authors’ qualifications (Goodman is a well-known veteran car enthusiast with extensive Edwardian sources, and Fasal, who had already published an incredible work entitled The Rolls-Royce Twenty, is a well-known enthusiast and very knowledgeable in the area of high-quality publishing); and “An Appreciation” by the current Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, who’s father, the second Lord Montagu, was so closely tied with Rolls-Royce from the very beginning and owned several of their earliest cars. These crucial introductory pages properly set the stage for all that is yet to come.

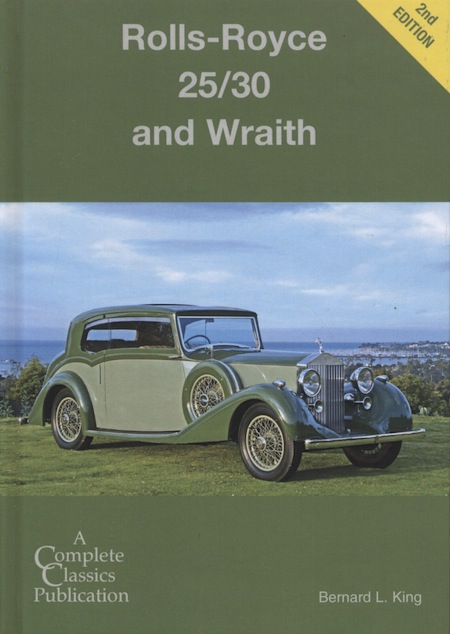

Section one, authored by Tom Clarke (known for his surpassing book The Rolls-Royce Wraith as well as many other benchmark-setting works about the history of Rolls-Royce cars and people), carries us through the first three prototype “Royce” cars and all the Rolls-Royce models that followed before the Silver Ghost: a two-cylinder 10 hp (essentially the Royce car), a three-cylinder 15 hp, a four-cylinder 20 hp, a six-cylinder 30 hp, and a 20 hp V8. The groundbreaking work in this area was done by C W Morton in his 1964 A History of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, Volume One, 1903–1907. Clarke makes reference to Morton and others, and sets out to expand the work, with corrections and much in new data. (Confession: this reviewer purchased the entire Edwardian just so that he could get his hands on Clarke’s section, particularly for the V8 data which is a special research interest of mine.) Like the rest of the work, the cars are presented chassis by chassis. There is significant narrative to advance the body of knowledge along with thoughtful analytical tables.

Section one, authored by Tom Clarke (known for his surpassing book The Rolls-Royce Wraith as well as many other benchmark-setting works about the history of Rolls-Royce cars and people), carries us through the first three prototype “Royce” cars and all the Rolls-Royce models that followed before the Silver Ghost: a two-cylinder 10 hp (essentially the Royce car), a three-cylinder 15 hp, a four-cylinder 20 hp, a six-cylinder 30 hp, and a 20 hp V8. The groundbreaking work in this area was done by C W Morton in his 1964 A History of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, Volume One, 1903–1907. Clarke makes reference to Morton and others, and sets out to expand the work, with corrections and much in new data. (Confession: this reviewer purchased the entire Edwardian just so that he could get his hands on Clarke’s section, particularly for the V8 data which is a special research interest of mine.) Like the rest of the work, the cars are presented chassis by chassis. There is significant narrative to advance the body of knowledge along with thoughtful analytical tables.

Section two deals with Silver Ghost chassis from late 1906 to July of 1911. Each listing contains chassis and engine number, coachwork (many had multiple bodies over time), coachbuilder, body number, the work’s test date, the finish, and the registration number (which, in England, stays with the car and can be a key aid in identifying cars in photos). Under this listing, the narrative describes the various owners in chronological order, along with any other relevant data. As mentioned, the data is broken up by pictures of the cars, as well as other picture data. To give you an idea of the level of detail, here are some captions from page 388/9—just imagine the pictures: “The test track was laid behind the Derby works in 1911 but had a short life, being built over to increase production space during the Great War. Cars can be seen, with bonnets removed, on test in 1911.”; “An unscheduled view of 1911 chassis after turning over on the Derby works test track. This shows the ladder-type frame, back axle with open propeller shaft, radius rods and bald tyres!”; “A 1911 engine on power test.” A great number of these photos– even ones that already been published elsewhere—were shot anew from original prints and negatives (glass and film) so as to have the highest possible quality.

Volume II (449 pages) takes us from the end of July 1911 to July 1917. The last sections are devoted to: design modifications and major model types; a reprint of the 1913 company publication Memoranda on Fitting Coachwork and Completing Rolls-Royce Cars; and a Name Index that ties owner names to chassis listing. Another fifteen pages of owners’ names came to light just as typesetting was completed for the book so while those names could not be incorporated on the pages themselves they are reflected in the Index.

There are also a few goodies included. First, each book has a Rolls-Royce–themed bookmark, affixed to the inside of the spine. Second, each volume has a paper pouch on its inside back cover containing a large, removable, folded print: in Vol. I a 9 x 34˝ line-up of Silver Ghost ambulances dated April 1917, and in Vol. II a 18½ x 24˝ newspaper page reprint titled “The CONQUEST of the ALPS” from the November 1913 The Times (If you buy a used copy be sure these are present!) While it is to be expected that the photography would be in black & white, there are a few instances where the company produced colorized pictures, drawings and paintings and when those appear in these volumes, they appear true to the color originals.

There are also a few goodies included. First, each book has a Rolls-Royce–themed bookmark, affixed to the inside of the spine. Second, each volume has a paper pouch on its inside back cover containing a large, removable, folded print: in Vol. I a 9 x 34˝ line-up of Silver Ghost ambulances dated April 1917, and in Vol. II a 18½ x 24˝ newspaper page reprint titled “The CONQUEST of the ALPS” from the November 1913 The Times (If you buy a used copy be sure these are present!) While it is to be expected that the photography would be in black & white, there are a few instances where the company produced colorized pictures, drawings and paintings and when those appear in these volumes, they appear true to the color originals.

As always, it would be folly to expect one book to answer all questions. The authors recognize that much of the “car/company story” will be found in works such as Morton’s book, and, almost in contrast, the three-volume work The Magic of a Name by Peter Pugh which is a business history and barely touches on the cars proper. The authors recognize the possibilities of errors, given the nature of the source material. (Rolls-Royce itself made mistakes in its own record-keeping—and is hardly alone in that!) The authors note that, often, it was process of elimination that would identify certain pictures. One error must be disclosed to make a point: on the bottom of page 163 we see chassis 60558, but it is actually chassis 60557 that went to H.L. Edwards of Texas—a fact that only emerged when Edwards’ descendants produced a picture in recent years with the same occupants taken on the same day. The fascinating point here is that the identification was made within one chassis number for the book!

It is often said that a book review is not a book report. However, as mentioned earlier, I purchased this two-volume set primarily to get my hands on one narrow piece of its wealth, and did not initially appreciate the fullness of its scope. This work is easily the cornerstone for any serious automobile library or book collector, not just in matters Rolls-Royce but veteran cars in general. In covering the era of the Edwardian Rolls-Royce, it is second to none.

Copyright 2011, Rubén Verdés (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter