The Industrial Revolutionaries: The Making of the Modern World, 1776–1914

by Gavin Weightman

by Gavin Weightman

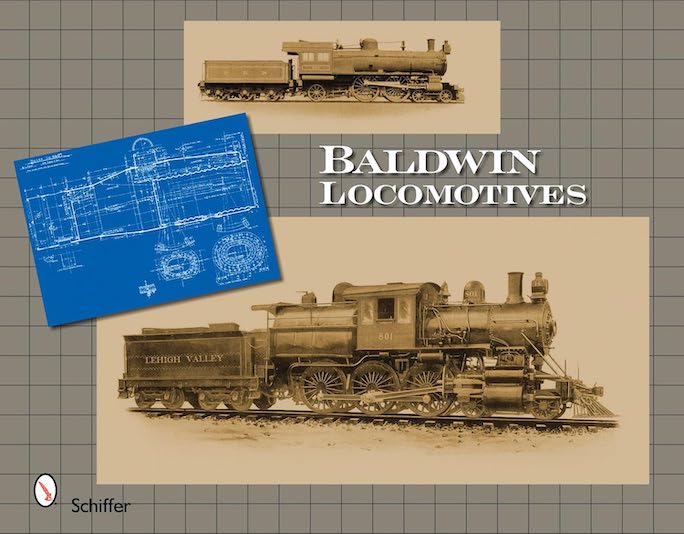

This book is akin to reading, as opposed to watching, the out-takes that so often accompany re-releases of popular movies on dvd. The out-takes that fill the pages of this book, however, are from behind-the-scenes of the major, most important and influential inventions of all time. Think railroads and locomotives, coal and petroleum into useable energy and, by extrapolation, internal combustion engines—and how all of this budding technology traveled back and forth across oceans.

As illogical as it may seem, one chapter alone takes the reader from the mechanical innovation named after, but not invented by, Dr Joseph-Ignace Guillotin (on the European continent) to the invention (in North America), of the means to mass-machine ship’s pulley blocks but which then had to go back across the ocean to actually be produced in England. Then almost immediately the reader is transported back over the Channel to where the chapter began in order to be introduced to “another French émigré who found the United States provided an opportunity to establish what turned out to be one of the greatest companies of the nineteenth century…” Have you already guessed? It is none other than Pierre DuPont.

The railway saga is about engines, but tracks too and, of necessity, that ties in (sorry, pun just slipped in) and tells about coal to coke and steel. The earliest rails were made of wood with a crudely-smelted metal overlay (rails made of solid steel aren’t a reality until a few chapters later) that often warped and as they wore fasteners pulled loose and suddenly the wood floor of a passenger car was violently penetrated, injuring and in some instances killing passengers. It took time for mankind to master the use of anthracite and bituminous coal, learn how to superheat the raw materials to make steel, and persuade people that there was a better way than digging and flooding canals, then floating barges pulled by horses or mules walking alongside, to transport themselves and their goods. Reading this book, you too will more fully appreciate the challenges faced and overcome before realties we now take for granted were achieved.

This book offers the reader insights behind the usual recitations of history and reference books. Gavin Weightman, described as a social historian, spent time researching in the London and British Libraries, the Rockefeller Archive Center in New York, and reading volumes of volumes as the bibliography attests. It should surprise no one that he discovered that, “tens of thousands of significant individuals were involved in the creation and spread of industrial societies.” Happily for us, unlike those mainstream history and text books, Weightman had the ability to share the behind-the-scene events, reveal the names, and (with this book as the vehicle, if we but read it) enlighten us all.

Do you know about Abraham Gesner or Thomas Cochrane? According to Weightman these two, Gesner a Canadian and Cochrane a Scot living in Halifax, are the two most responsible, and mostly unheralded, for figuring out how to refine and make black gold universally useful. Subsequently, of course, that means they made possible what we now refer to as “the age of steel”.

Worthwhile as the information is, it is the author’s style—how he describes people, places and events—that engage the reader. The thirteenth chapter sparkles, appropriately reflecting its subject, the Crystal Palace. The design and construction were controversial. Organizing the exhibition of “achievements in engineering and manufacture” that it was built to showcase was challenging, but ultimately, “The draw of the Exhibition…proved irresistible”. European countries participated, as did China, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Persia, Greece, Turkey, and Egypt. Among the displays that represented the United States were Cyrus McCormick who showed and demonstrated his reaper, Charles Goodyear with his process for vulcanizing rubber, along with Samuel Colt and his fast-firing revolver, while the New York-made yacht America sailed and bested all comers.

Weightman chose to end his narrative with 1914 simply because, “to take it any further into the twentieth century would be too cumbersome and, anyway, all the essentials are in place by then: petrol as well as steam engines, electronic communications including wireless, electric light and electric motors, iron ships and heavier-than-air flying machines. As the first industrial nation, Britain had by then already lost ground to the United States and Germany, and a familiar pattern had emerged as the built-in obsolescence of all technologies was revealed.” It’s all there for you to read, learn from and enjoy through the well-crafted words of The Industrial Revolutionaries.

Copyright 2009 Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Just finished reading this book. Great read!

I haven’t read this book yet but I do look forward to doing so.

1914 seems to be an appropriate place to end this history of the industrial revolution with the world war that the industrial revolution sparked and fueled. You had the machines and materiel provided by industry in the hands of governments with pre-Industrial Revolution mentalities.