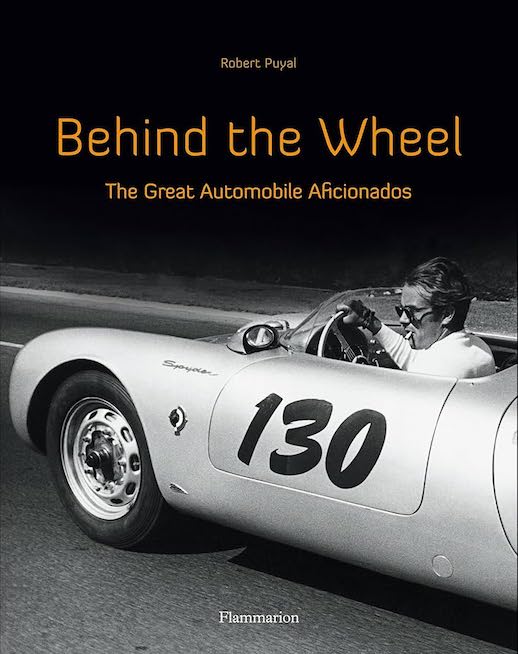

Porsche and Me

by Hans Mezger with Peter Morgan

by Hans Mezger with Peter Morgan

For four decades, Hans Mezger designed engines that put Porsches on the top of leaderboards and ahead on the road.

Be it your 911 grocery-getter or the indomitable 917 that finally gave Porsche a Le Mans win, all Porsches of the modern age benefited from Mezger’s slide rule. Any one of his projects would make an engineer think he left the world a better place than he found it, but Mezger’s list of professional successes is uncommonly long—probably for the same reasons his personal life is not without enviable accomplishments (long marriage, healthy relationships with the kids): he applies himself, sticks with it, is of a temperate disposition. A good guy, in other words.

How is it then that “one of the most important engineers in Porsche’s history”—as the firm’s bosses lauded Mezger (b. 1929) on the occasion of his 80th birthday—is so little known outside of professional circles? It’s because he kept and keeps a low profile, mindful that his own efforts and abilities do not exist in a vacuum but that his team, inspired company leadership, and plain luck of being in the right place at the right time play a role.

It is a good thing that Morgan had both the motivation and the means to rectify this state of affairs and enrich the literature by adding Mezger’s story to the record. As former head of the Race Design Office Mezger is an obvious resource to researchers and it is in that capacity that Morgan, a mechanical engineer by training who has penned over 20 Porsche books, crossed paths with him some 15 years ago. About three years ago he started interviewing Mezger and the resulting 35 hours of transcripts are the basis for this autobiography.

Between joining Porsche right out of university in 1956—when the firm was just beginning to carve out its place in the world—to his retirement in 1994, Mezger has touched everything that made the company’s products and ethos great: the 1.5L 8-cylinder Porsche 804 F1 that gave Dan Gurney the French GP win in 1962; the 907, 910, 908, 909, 917, 935, 936, and 956/962 racers; the 6-cylinder boxer in the 911; groundbreaking work on turbo engines for race and road cars, especially the “TAG-Turbo made by Porsche” for McLaren (whose chief, Ron Dennis, wrote one of the Forewords; the other is by Ferdinand Piëch) that would become the most successful turbo in F1, winning three drivers’ and two constructors’ championships.

All of the above and more is covered here. Some of the extracurricular activities the race office was tasked  with are presented in a stand-alone chapter, fittingly called “Outside Work.” Some of these are fairly well known, such as the V-twin engine for Harley-Davidson or an aluminum crankcase for a Daimler Benz V8 and certainly the twin-clutch automatic. Others may well surprise even the well-read Porsche enthusiast: the cabin for the Wagner helicopter, a Chrysler sports car with a 944 engine, a turbocharged Chrysler, or Russian interest in a road car for the home and European market. The latter are covered in tantalizing brevity, probably because many of these projects did not go beyond the concept stage.

with are presented in a stand-alone chapter, fittingly called “Outside Work.” Some of these are fairly well known, such as the V-twin engine for Harley-Davidson or an aluminum crankcase for a Daimler Benz V8 and certainly the twin-clutch automatic. Others may well surprise even the well-read Porsche enthusiast: the cabin for the Wagner helicopter, a Chrysler sports car with a 944 engine, a turbocharged Chrysler, or Russian interest in a road car for the home and European market. The latter are covered in tantalizing brevity, probably because many of these projects did not go beyond the concept stage.

Even if you can recite chapter and verse of the mainstream Porsche literature, you’ll find in Mezger’s recollections the sort of detail only an insider would possess. There’s quite a bit here about the atmosphere in the workshops, the quality of the interaction between management and workers, the sense throughout the company of being “family” and doing something special—but also the loss of that esprit de corps and motivation in later years in the wake of management changes and company politics. On both ends of the spectrum, a personal account like this paints a rich picture of what makes a company tick in a way that no glitzy coffee table book with sexy car photos can.

There is also quite a bit of fairly serious engineer-speak—rather to be expected from someone who reveled in math and science already in high school. As soon as the first chapter is done relating family background, be prepared for discussions of how rocker arm profiles affect leverage ratios and other such intricacies. To someone who enjoys general math and what Mezger calls “descriptive geometry,” this is actually truly fascinating. Even if it is not your cup of tea at all and you just skim these passages, you will get a sense for just how hard a job it is to engineer a good car, or a good anything.

Photos are plentiful, some even new to the record. (Probably mostly the ones from Mezger’s own collection; none are credited so it’s hard to know.) Everything the text covers is suitably illustrated, offering even engineering drawings, staffing charts, and various correspondence. The latter is only sometimes translated (which usually includes annotations such as job titles or the like) but everything is quite thoroughly captioned.

Morgan calls this book “one of the most satisfying projects of my writing career.” The world is a better place for having it, to be sure. It advances the record, says and shows new things, and presents to the world at large the manifold contributions of a key architect of Porsche’s success. It took long enough to get written, being first slated for a May 2010 release. You only have to turn a few pages to begin to wonder if a need to “wrap it up” is the reason for the transcripts reading so inelegant or the rather too many misspellings of foreign words. Perhaps Morgan wanted to “preserve” Mezger’s voice but the English text has an undeniable German architecture (an example, from p. 3: “. . . he had come safe home.” Or p. 41, about Piëch’s school [which is misspelled]: “Naturally he knew much more about Porsche than a normal High School leaver.”) Consider, too, that Mezger’s Introduction to this book, or the one to Wingrove’s 2006 Porsche 917 book (same publisher), read much more fluidly. Authenticity is a legitimate criteria, but an editor worth his salt should move heaven and earth to make his writer look good. Mezger deserved better!

Five Appendices present Mezger’s major awards/citations, a 1981–84 timeline of the TAG turbo project and a breakdown (event, date, driver, position) of its 1984–87 competition record, a 1962–1990 survey of “landmark” Mezger engines, and a full reproduction of his 1972 paper to the IMech on the 917 development. Good Index.

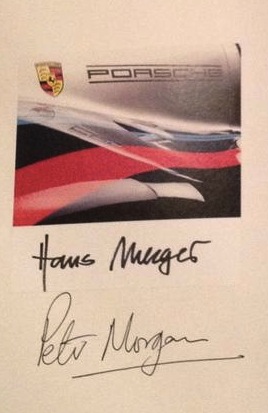

A special limited edition (ISBN 978 1906712 129) of 125 numbered and signed copies by Mezger and Morgan was released at £90 and is sold out. While it was given an upscale treatment of finer cloth and a slipcase with silver embossed lettering, Mezger’s signature is only pasted in.

A special limited edition (ISBN 978 1906712 129) of 125 numbered and signed copies by Mezger and Morgan was released at £90 and is sold out. While it was given an upscale treatment of finer cloth and a slipcase with silver embossed lettering, Mezger’s signature is only pasted in.

Copyright 2011, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter