Bugatti: Carlo, Rembrandt, Ettore, Jean

by Amanda Dunsmore, John Payne

by Amanda Dunsmore, John Payne

“The mythology surrounding this family, both of their own making and by those who have fallen under their spell, is as diverting as it is frustrating.”

From grandfather (Carlo, 1856–1940) to grandson (Jean, 1909–1939), three consecutive generations of Bugattis have made highly original and sophisticated contributions to their respective fields in the decorative and applied arts. In between these two are of course Ettore (1881–1947) and his younger brother Rembrandt (1884–1916). While these four are the topic of this book, there are, in fact, even more Bugattis who have made art, married into art, or attended to the less glamorous task of making the art of others possible.

Ettore’s approach to the design and engineering of his cars cannot be fully appreciated outside of the context of the larger family’s shared creative impulse. In this regard it is noteworthy that it was Ettore (the first son, preceded by a sister) whom the family intended to don the artist’s mantle and Rembrandt who was to become the engineer. It is only thanks to the chance discovery of an accomplished clay sculpture by the then 14-year-old and essentially self-taught Rembrandt that history took a different course.

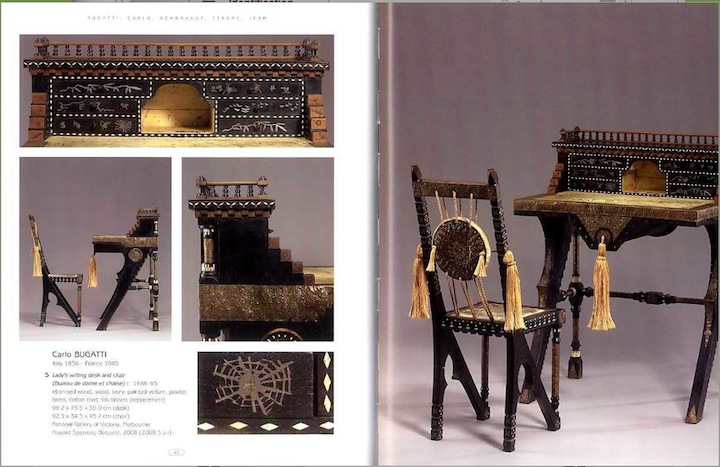

Australia is not exactly a hotbed of Bugatti artifacts and it wasn’t until 2006 that the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) purchased its first item, Carlo Bugatti’s ca. 1900 “Throne” chair. That initial acquisition raised interest in others and by 2009 enough artifacts of sufficient variety had been bought by or donated or lent to the NGV to mount a first-ever full-scale exhibition of representative Bugatti works in Australia.

This book is occasioned by and based on that 10-week gallery exhibit. It is as true as it is redundant to observe that it is also limited by the scope of the exhibit which “only” featured some 30 items, only two of which cars. Exhibit and book are co-produced by NGV staff Amanda Dunsmore, Curator Decorative Arts & Antiquities and John Payne, Senior Conservator of Painting (and life-long Bugatti car enthusiast). The book is more than just a catalog of the show inasmuch as it reaches beyond the items on display and offers a comprehensive appraisal of the Bugattis’ influences, output, and accomplishments.

Dunsmore, as evidenced by the quote above, is mindful of various loose ends and shortcomings in the handed-down literature but is quick to point out that their book is “in no way intended as a revision of Bugatti scholarship, but rather, is a summarized account of our understanding to date.” A Bibliography directs the reader to other treatments.

An opening chapter introduces the principals in fairly succinct biographical sketches giving a good account of their personalities and strengths/weaknesses, and an overall survey of each person’s oeuvre. Key themes here are the distinction between artist and craftsman, a perhaps uncommonly acute esthetic (each man designed his own clothes!), and an almost innate creative urge coupled with “a proud belief in an unschooled intuitive ability to create,” the latter meaning not so much the spark itself, the idea, but the technical skills to translate the idea into form. To varying degrees all Bugattis underwent some sort of often rudimentary formal training but, in the main, they learned on their own and on the fly.

The story begins, naturally enough, with Carlo but it is not apparent why the chronological treatment is abandoned with the next person featured, Rembrandt, who was born three years after Ettore. He did manifest his abilities somewhat earlier than Ettore and in his short life did achieve more fame and financial success than any of his contemporaries. Perhaps grouping him with Carlo keeps the “fine art” aspect together so that Ettore and his son Jean can make up the “car” pairing.

Each piece in the show is then shown on one to several pages; there is no description other than one photo caption listing name, material, dimensions, and current location. The two cars shown—both went to Australia new—are Ettore’s 1926 Type 37 racing car (chassis 37146) and Jean’s 1938 Type 57C Atalante (chassis 57788), along with a Type 44 engine (from chassis 44926) and a pair of cast aluminum wheels.

While there are plenty of detail photos, the absence of text probably leaves the viewer a bit hanging. All the captions are reproduced at the back of the back in an “Exhibition Checklist.” An 1856–1980 timeline puts everything in its proper place; in fact, this would be a good way to start the book.

The publisher is a Bugatti (car) enthusiast and has devoted an entire book to one particular model, the Brescia.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter