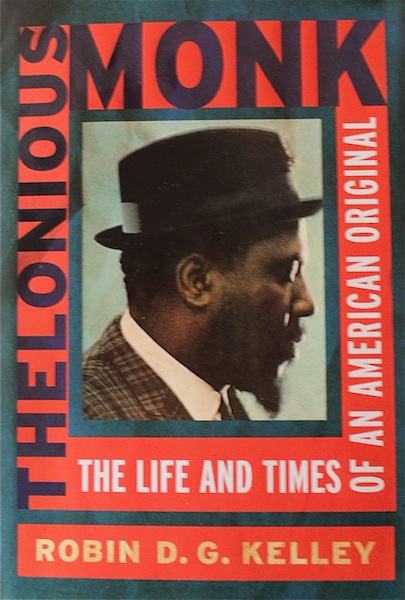

Thelonious Monk

The Life and Times of an American Original

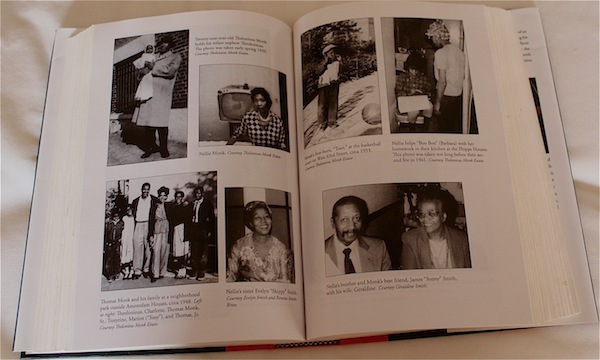

By the time of the breakup of the Beatles in 1970, all four of the Mop Tops were well on their way to being very rich men; Sir Paul McCartney today is a billionaire. In 1970 Thelonious Sphere Monk, the 53-year-old jazz legend, a brilliant, fabled composer and pianist “had to hustle for work.” Through the decades, Monk led a reasonably secure New York City middle-class life with his beloved Nellie and their two children, but if it wasn’t for the generosity of a loyal patron, the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, neé Rothschild (yes, those Rothschilds), what with the sometime scarcity of gigs, various health problems both physical and mental exacerbated by questionable “cures,” apartment fires (the Monks suffered through two), creative accounting by record labels, and the sometimes acerbic and off-putting effects of Monk’s bipolarity, the man and his family would have found themselves too often in tough financial straights. That life is unfair is universally accepted, but that doesn’t prevent a certain stab of sympathy and a lash of anger from penetrating through any right-minded person’s need for compassion and quest for justice. The myth of the destitute, unappreciated artist toiling in a garret has a stout enough base in reality and may elicit sympathy or derision from both dreamers and realists alike, but that is not Monk’s story. All through his life he was lauded, nearly always critically acclaimed, and recognized as a prime contributor to music, and his story and that of the art, the finances, the family, the friendships, is superbly told by Robin Kelly.

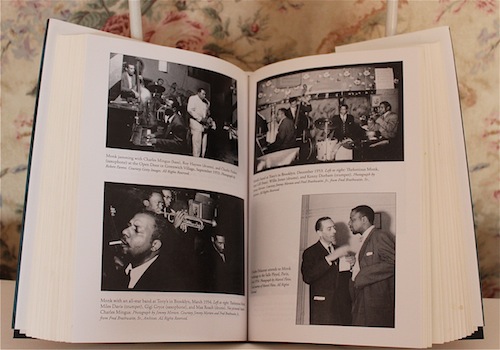

Monk was published in 2009 and at the time Kelly was the Professor of History and American Studies at the University of Southern California; he had already at least three books under his belt. Over a decade was spent on the research and writing of Monk, and an abiding and enormous scholarship is evident throughout—in the 5 1/2-page list of Monk’s original compositions, the six pages of acknowledgements, the 15-page index, the text riddled with superscripted numbers like friendly gnats that refer to 99 pages of notes. By its nature, a biography of a jazz musician, along with stories of friends and the history of family, needs be a laundry list of sidemen, colleagues, compositions, recording dates, club dates, festivals and concerts, but this does not prevent Kelly from solidly keeping the reader’s attention, always making it easy to want to turn yet another page. The composite personality of Monk, his peculiarities, his heart, sometimes warm, sometimes cold, his taciturnity, his garrulousness, his generosity of spirit also help Kelly keep the reader’s attention curious and alive.

Monk was published in 2009 and at the time Kelly was the Professor of History and American Studies at the University of Southern California; he had already at least three books under his belt. Over a decade was spent on the research and writing of Monk, and an abiding and enormous scholarship is evident throughout—in the 5 1/2-page list of Monk’s original compositions, the six pages of acknowledgements, the 15-page index, the text riddled with superscripted numbers like friendly gnats that refer to 99 pages of notes. By its nature, a biography of a jazz musician, along with stories of friends and the history of family, needs be a laundry list of sidemen, colleagues, compositions, recording dates, club dates, festivals and concerts, but this does not prevent Kelly from solidly keeping the reader’s attention, always making it easy to want to turn yet another page. The composite personality of Monk, his peculiarities, his heart, sometimes warm, sometimes cold, his taciturnity, his garrulousness, his generosity of spirit also help Kelly keep the reader’s attention curious and alive.

And there is one other important aspect of this book. The subtitle “The Life and Times of an American Original” is not just a literary cliché. Kelly paints a lively picture of the various jazz scenes throughout the decades, and he does not ignore the ugly history of racism that Monk had to endure. Kelly doesn’t dwell on this, but it is pervasive, always reeking in the shadows, ever eliciting American dread, horror and shame.

And there is one other important aspect of this book. The subtitle “The Life and Times of an American Original” is not just a literary cliché. Kelly paints a lively picture of the various jazz scenes throughout the decades, and he does not ignore the ugly history of racism that Monk had to endure. Kelly doesn’t dwell on this, but it is pervasive, always reeking in the shadows, ever eliciting American dread, horror and shame.

Truly a work of art—like the man and the music it honors.

Copyright 2013, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Dear Bill,

Thanks for passing on this extraordinary review. I really appreciate it, your thoughtfulness and generosity especially. Sorry it took so long to get back to you; I’ve been inundated with the end of quarter crunch, working 24-7 just to get my grades in and make a few writing deadlines.

Thanks again and happy new year,

Robin

Gary B. Nash Professor of U.S. History

University of California at Los Angeles