Watching the Wheels, My Autobiography

“It is the stuff of legend how my father knew no one, had no money, but would sit in the Steering Wheel Club in Mayfair and make half a pint last all night in order to be in the right place to meet the right people. There are countless stories describing a person who would not give up until he had given things his best shot. For the son of such a man, that is both inspiring and a lot to live up to. My father gave the name ‘Hill’ a certain meaning. It carried all the qualities of the legend with it. If I was going to be a true Hill, I would have to earn it.”

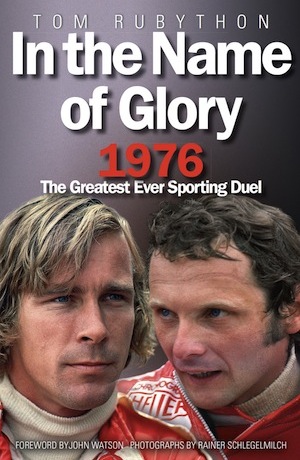

I last saw the author’s father, Graham, when he drove his farewell lap at Silverstone in 1975 and everybody knew it was at least five years too late. He had become a makeweight on the Grand Prix grid and at the age of 46 the former King of Monaco had long since lost his crown. The fact that Damon Hill is now a decade older than his father was when his Piper Aztec crashed on that foggy night at Arkley Golf Course is remarkable to this baby boomer reader, if not as remarkable as the fact that he won 22 Grands Prix, eight more than his father’s total. But this superb book contradicts the convention that one should always judge the art and not the artist. This is a far better book for my having judged the artist more than the art, as Damon Hill is an extraordinary man. We usually read a racer’s life story to reinforce our own knowledge and to supplement the information we’ve already gained from having watched races on TV and having read about them in specialist magazines. This book contradicts that stereotype. Damon Hill uses the 385 pages to reveal that he’s a man who is flawed, anxious and conflicted; that self doubt and depression have been his regular companions and that he is a man whose father’s legacy has quick-sanded everything he has ever done.

Damon knew all about Grand Prix racing as a child because he had played a bit part in the Graham Hill soap opera since he could walk. He’d had endless photos taken in F1 paddocks, had grown tired of their tawdry glamor and of being asked endlessly whether he was going to follow in Dad’s footsteps. Damon’s childhood could never have been conventional and he writes candidly about his father’s larger than life public persona and the effect that it had on his family. It especially impacted his mother Bette and placed great stress upon their marriage—“Do we really think Odysseus resisted all the temptations he encountered on his voyages, or that he never incurred the wrath of Penelope when he came home late from the Trojan War?” After retiring from motorsport Hill studied for an Open University degree in Literature, gaining a First, and the Classical references and the elegance of the prose bear testimony to this. Some input was given by journalist Maurice Hamilton but the essence of the book is Hill’s work alone.

The circumstances of Graham Hill’s death are well known (also see his own book, Life at the Limit [1993], ISBN 978-1852604615) but the effect on the family rather less so; suffice it to say that Damon’s account of the accident’s repercussions and his reaction to it—grief and anger key among them—will resonate with anybody who has had to cope with the sudden loss of a family member or close friend.

But teenagers are resilient, and Hill got on with his own life. He wasn’t destined for an academic career but, instead, found himself in his love of music and, unlike most racing driver contemporaries, his taste was anything but mainstream. Instead of listening to Dire Straits and Phil Collins, his music was the anarchical assault of the Sex Pistols and the Ramones, who he would go and see live at London’s Marquee Club. In 1981 he also met the love of his life, Georgie, now the mother of his four children and as far removed as possible from the stereotypical “pit lane popsy” of his father’s era. The reader comes to realize how Hill has been grounded by Georgie’s rock-like stability.

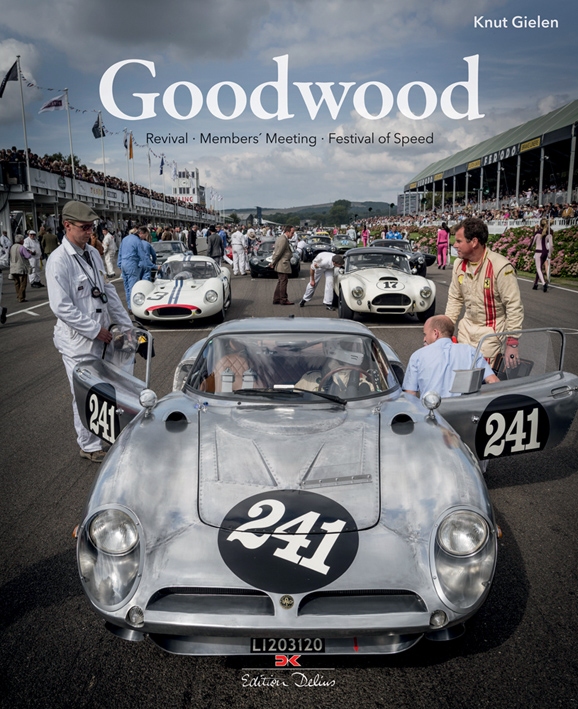

Hill also loved what he termed “the counterculture of bikes” and he enjoyed successes on Kawasakis and Yamahas, racing being funded by laboring and dispatch riding work—no silver spoons were left in this family after the events of 29 November 1975. The transition to four wheels was inevitable and although he enjoyed sporadic success he seemed just another struggling club racer when I saw him race in Formula Ford 1600 and Formula 3. But what Hill thrived on was managing an excess of power over grip and whilst that was never a challenge in 160 bhp F3, the numbers got serious in 450 bhp F3000 cars and so did Hill. His journey into Formula One is well known and whilst the text describes the pressure cooker world of F1 effectively it is the first-person insight that shines the brightest. The account of Senna’s death and its repercussions is compelling, and even more remarkable is how Hill’s 1994 season eerily echoed his father’s 1968 season after Jim Clark’s death. Many readers may have forgotten that Damon also was present at Goodwood when his F3 teammate Bertrand Fabi was killed in testing and Hill’s reaction to that was telling: “Big boys don’t cry, I told myself and, after some serious soul searching and reminding myself that my father had coped with all this, I looked to place my budget with another team, Murray Taylor Racing Racing.” (The Dick Bennetts Team having stopped its F3 program after Fabi’s death.)

Possibly the only thing Damon Hill and Eddie Irvine had in common was having a robust enough ego to admit that Michael Schumacher was a more gifted racing driver than they were and, whilst Hill doesn’t gloss over Schumacher’s “win at all costs” cynicism, he is unstinting in his admiration of the German’s otherworldly talent. But Hill doesn’t sell himself short either, especially in his account of his finest hour (and one of the best Grands Prix I have seen), the Japanese Grand Prix in 1994. Suzuka has so often produced drama on an epic scale but the ’94 race was nothing short of majestic , as Hill drove out of his skin to beat Schumacher, and in the wet too—“the great leveller/” Hill recounts how he sought Senna’s help towards the end of the race, “if you’re up there.” It worked too “I was possessed . . . I was just an observer of something phenomenal.” And so was I, and just like Murray Walker I had “a lump in my throat” when, after snatching defeat from the jaws of victory in 1995, Damon Hill won the World Championship in 1996, fittingly at Suzuka.

The glitter of 1996 swiftly tarnished in 1997 when Hill drove for Arrows—hopeless nearly everywhere except Hungary—and his account of team boss Tom Walkinshaw’s attitude to cheating is illuminating if not totally surprising. 1998 saw Hill driving for the ebullient Eddie Jordan and, by all accounts (including this one) the only people who weren’t overjoyed at Hill giving the Jordan team its debut Grand Prix win at Spa were both called Schumacher. But by 1999 it was all over; Hill recounts how he was beset by self doubt and anxiety: “I’d done enough denying the fear; my motivation had entirely gone.”

With few exceptions I am often no better informed of a racing driver’s true character after reading his autobiography than I was beforehand. They are usually ghostwritten, often poorly, and they are often produced in haste to cash in on a world championship (this book is published on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Damon’s World Championship win). They rarely tell me anything I didn’t already know, targeted as they are at a largely uninformed market. Watching the Wheels (the words being a quote from a John Lennon song) doesn’t fall into this category. Hill’s book is compelling, brutally honest, and quite unforgettable.

Paul Simon once wrote a song called “Think too much” and, whilst doing so may have been a curse for Hill the driver, it has proved to be a blessing for any reader of Hill the writer.

Copyright 2016, John Aston (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter