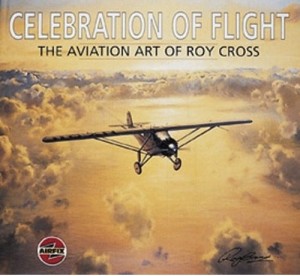

L-15 Scout, Boeing’s Smallest Airplane

by Mal Holcomb

by Mal Holcomb

“The L-15 Scout was Boeing’s smallest airplane, but it was designed using large-airplane philosophy. Its ultimate value was in keeping the Boeing Wichita division in operation, ensuring its availability for the later B-47 Stratojet production program.”

Say the word “Boeing” and the vision that comes to most folks is of large aircraft capable of transporting great numbers of passengers and their luggage with space still available for cargo. Those visions are not wrong.

But did you know that Boeing once designed and built a small high-wing tandem pilot-forward two seater? It did and this book tells the full story of that aircraft. It tells it well and in great detail too because the author is aviation-technically oriented with the resources to fully tell of Boeing’s L-15.

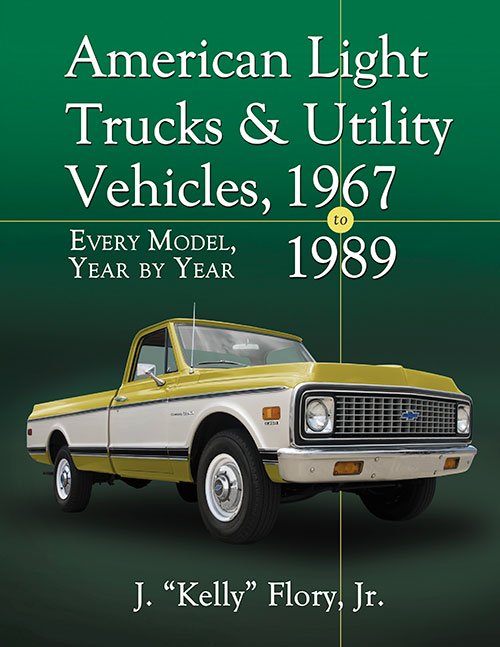

As peace returned after WW II, families and companies—any and all businesses—tried to understand what life would be like. The automakers were constrained by the still scarce supplies of steel and other necessary manufacturing materials. As they returned to production the vehicles were essentially only slightly updated versions of their prewar-made vehicles.

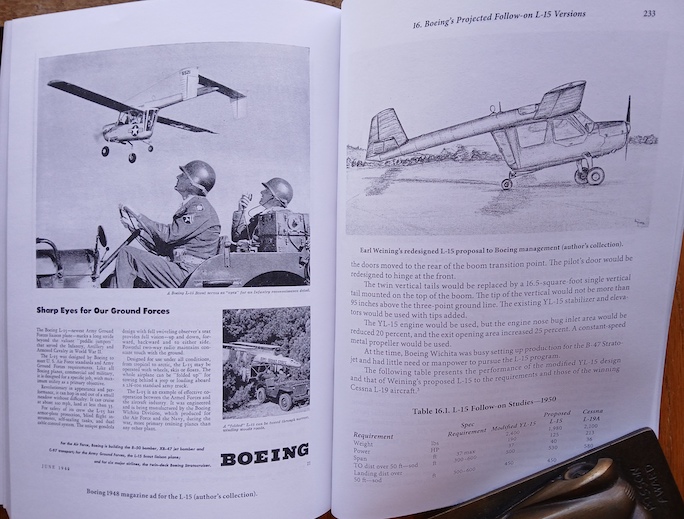

On left, a magazine ad telling of capabilities of a military L-15. Facing page is an unsolicited (by Boeing) redesign proposal from project engineer Earl Weining.

Aircraft makers had a bit larger challenge, for their planes to win war didn’t “translate” to civilian use. Some forecast that postwar there might be a really good chance that the average home would have a car and a light, personal aircraft in every garage. That led many aircraft makers to explore what those personal aircraft might be like and those ideas open this book. However, “In retrospect looking at the actual postwar light plane picture, the huge production prediction and the expected prevalence of safe simplified airplanes did not become a reality.”

But when the military sent out a request on Feb. 4, 1945 for bids (RFB) for “flight vehicles . . . to meet the ‘Military Characteristics of Field Artillery Observation Aircraft,’” Boeing would be among those submitting designs and specifications.

The reader already somewhat versed in aviation will gain the most from these detailed specifications and design criteria as the author, Mal Holcomb, is a retired aeronautical engineer with extensive experience in general aviation aerodynamics, aircraft design, and flight testing. Thus, chapter by chapter he writes a thoughtful, informed, and detailed account of the Boeing L-15 story documenting what has, until now, been a rather obscure aircraft.

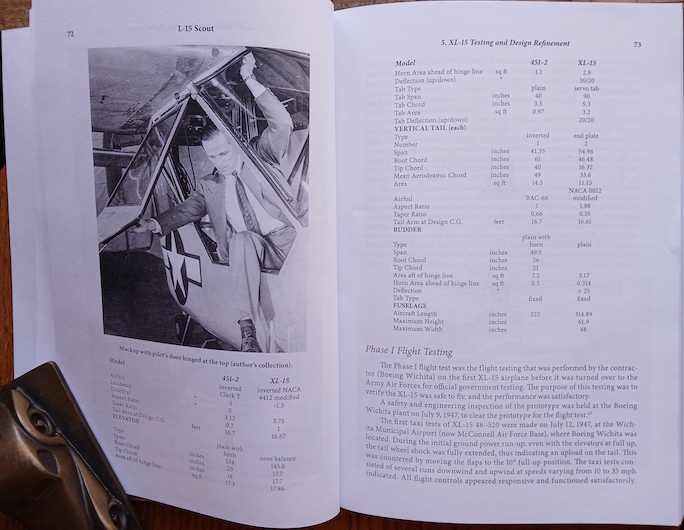

Chapter by chapter Holcomb discusses each system of the L-15 one by one; performance, propulsion, landing gear, handling and maintenance, and more. With his discussion on the aircraft’s airframe he notes an anomaly he cannot account for. The pilot’s door on the right side of the aircraft in production was aft-hinged to swing out but on the restored example it was inexplicably hinged at the top as shown in the image. The aft-facing observer’s compartment entry and egress was via “full- length vertical doors . . . hinged to swing outward.”

Photo is of the mock-up showing the top-hinged door during design phase and chart is part of multi-page document of “Geometry Changes from Bid to Prototype.”

The Scout’s landing gear “was designed with . . . provisions to operate on land, snow, or water. It could also be equipped for operating from a Brodie* system on land or ship.” Holcomb notes “it is not known if flight tests of the Brodie system were actually performed.”

As this book concerns itself with Boeing’s L-15, I am not aware if any of the competing aircraft designs featured the ability of the Scout to be “loaded on a standard military two and a half ton truck.” It could fairly easily be disassembled such that a Fairchild C-82 Packet aircraft “could carry two YL-15s.”

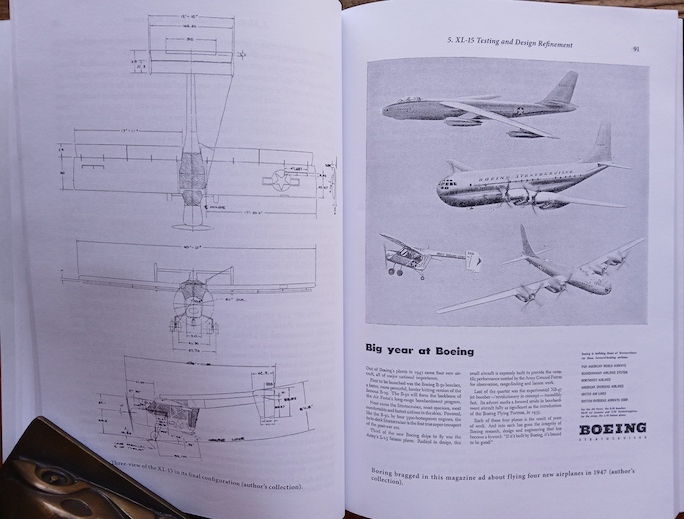

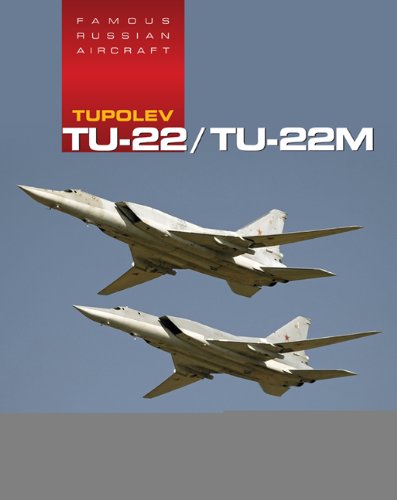

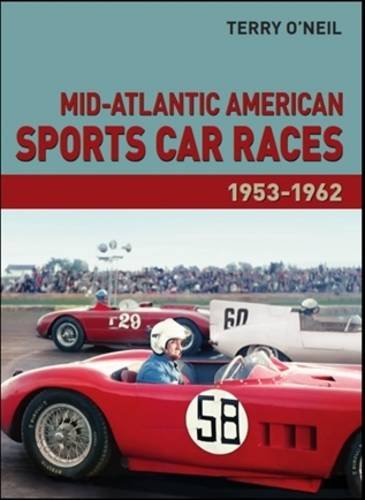

On left are three final configuration views of XL-15. Facing page is magazine ad in which Boeing touts its four new in 1947 aircraft; from the top a B-50 bomber, a Stratocruiser passenger airplane, an L-15, and an experimental XB-47 turbo-jet bomber.

So, what was the outcome of that competitive RFB? “The US Army did not accept the Boeing L-15 as a production liaison aircraft” as it scored less than the Piper-developed plane. But, as the opening quote indicates, “it enabled the Boeing Wichita division to stay in operation and be available . . . for the later B-47 Stratojet production program” as it was awarded the contract. Perhaps, too, in part because in the discussion paper published by the Air Material Command of Army Air Forces it was noted that Piper’s “commercial backlog being quite large, only forty percent is awarded [referring to the scoring on evaluation sheet] on Work Load” whereas Boeing received the “maximum Figure of Merit for Workload.”

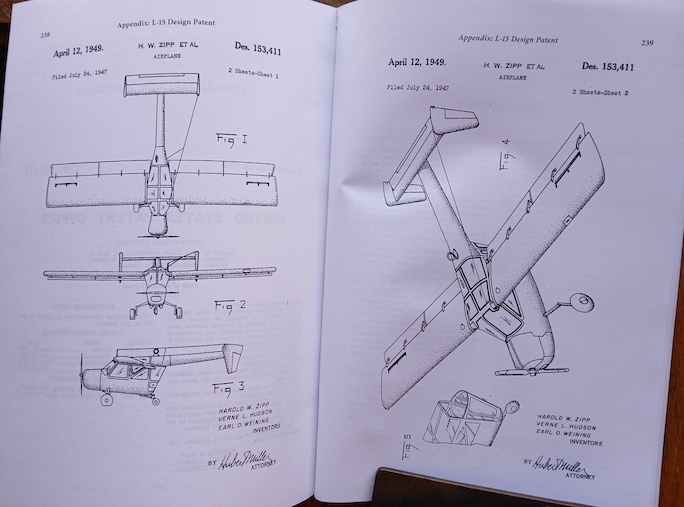

Two pages of the drawings part of L-15 Design Patent granted April 12, 1949.

By the time you’ve reached the last page of this most interesting book, you’ll have been enlightened regarding not just Boeing’s L-15 Scout but been exposed to aircraft development procedures and the behind the scene inner workings of letting a military contract. It’s an extremely well-organized and -written information-packed book.

* A system described as novel. It involved snagging an overhead hook attached to the aircraft by a cable secured between towers that acted as an arresting gear.

Copyright 2026 Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter