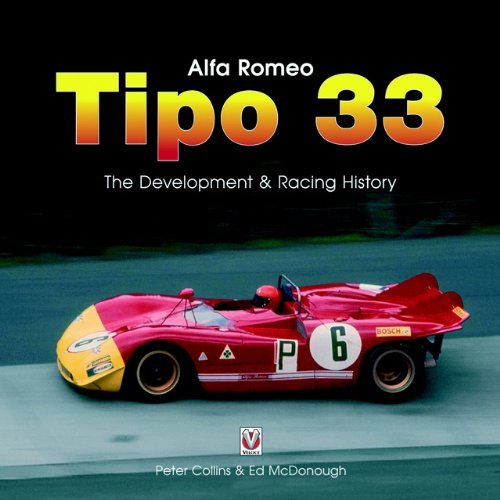

Alfa Romeo Tipo 33: The Development and Racing History

by Peter Collins and Ed McDonough

by Peter Collins and Ed McDonough

“. . . although co-writer Peter Collins and I had been committed to the idea for some three years and had been studiously gathering material on the Trenta Tre, often feeling it might have been easier to find, explain and build a replica of the Holy Grail.”

Success has many fathers, and so the reason so little has been written about this very successful car is largely because it is so difficult to sort out the validity of the conflicting claims by the various entities behind its success—the maker, Alfa Romeo; the engineer, Carlo Chiti; the racing organization, Autodelta—as to who did what when how. Created in the mid-1960s, among the race cars of its day the Tipo 33 is of course not alone in having little of its precise development history written down at the time but during its 10-year tenure it did see an uncommonly large number of drastic changes, partly in response to a commensurately large number of changes in racing regulations and technology. Chassis type 105.33 started out as a 2L V8 prototype, morphed into a 3L V12, and ended as a turbocharged 2.1L V12, all using different frames. Various concept cars were based on that chassis as well as the Stradale road car; all included here. One name, many models—a big topic then.

In their Introduction, the authors discuss the difficulties of distilling the one true story out of the multitude of accounts and turning the spotty history into a definitive, reference-level account. The book is that indeed, and well written to boot. They interviewed many T33 drivers, two of whom wrote Forewords—Nanni Galli and Teddy Pilette. Such first-hand accounts add, of course, depth but they too show that there is a considerable spectrum of opinion. The one thing this thorough book shies away from is an attempt at individual chassis histories. A second volume may tackle that—if ever sufficient clarity can be achieved as to chassis plates which, in some cases, even Alfa itself is known to have moved from car to car with no concern for record-keeping. This bit of minutia is not critical to the story the authors set forth here and the only people who will lose sleep over this are buyers and sellers of these increasingly valuable cars whose pricing is affected by provenance and race history.

For this first book, the authors required three different pieces of evidence to corroborate race claims. Photos play a great role in this and the Acknowledgements list a great number of people who helped in this regard.

McDonough, who was a race driver—in fact in the very series and at the very time the T33 competed—also specializes in track testing and can therefore offer relevant driving impressions of several restored T33 models here. Collins, a motoring journalist and photographer, took most of the photos of these road tests. Both authors have published widely on sports cars, and not only Italian ones, which is always helpful for having a large frame of reference.

The photographic record is extensive with over 400 images (none credited), well reproduced and properly captioned. Many more photos ended up on the proverbial cutting room floor and some of the particularly interesting ones care bundled into a six-page section of random uncaptioned shots at the back of the book.

Appended are 1967–1977 competition events for works racers, privately campaigned cars, and Stradales (as through as possible at this time but not definitive), an assortment of notes addressing “anomalies and conundrums,” and a list of those surviving cars that are not in doubt.

In the canon of Alfa Rome literature this book takes an important place. Writing it was a labor of love for the authors and they claim, rightly so, that it contains the “sum of the world’s knowledge” on this important model. If all you know of 1970s sports car racing is the Ford/Ferrari wars, this book will broaden horizons.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter