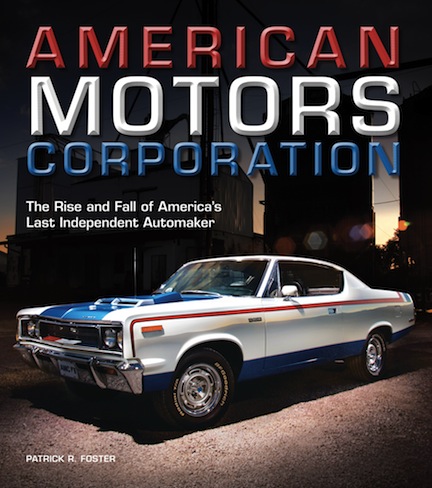

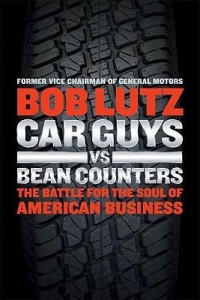

American Motors Corporation

The Rise and Fall of America’s Last Independent Automaker

The Rise and Fall of America’s Last Independent Automaker

by Patrick R. Foster

American Motors Corporation, or AMC, was formed in 1954 by combining the struggling Nash and Hudson car companies. From 1954 to 1963, under the focused leadership of George Romney, the joint effort survived withering competition from GM, Ford, and Chrysler. Eventually, after Romney left the company to pursue a political career, a streak of bad luck, bad management, a strike-prone militant union, and poor sales strategy all caused American Motors to become reluctantly acquired by Renault in the early 1980s, and then resold by Renault to Chrysler in 1987.

This book tells the story of that process from the beginning of AMC in 1954 to the end in 1987. All the important makes and models from that time period are displayed, with the major executives in the company quoted and their personalities described. Sales and production strategies are outlined along with why they worked or failed. The reader is also told why the acquisition of Jeep in 1970 saved the company, and how Jeep’s financial success eventually caught Chrysler’s eye and spelled doom for the AMC car line.

The book opens with two color photos that whet the appetite while simultaneously displaying what’s to come. A unique-looking 1955 Nash Statesman signifies where American Motors Corporation came from, then a Jeep CJ-5 shows us what saved AMC from bankruptcy. The final photo on the back cover of the book‘s dust jacket, a 1965 Marlin, symbolizes the managerial mistakes that finally killed the company, forcing AMC first into the hands of Renault, and then into the black hole of Chrysler Corporation where all semblance of Nash, Hudson, and Rambler disappeared forever. Only Jeep survived Chrysler’s event horizon.

The text is not an impersonal dry history book recitation of events as they occurred. Instead, the reader gets the feeling that author Foster, who at one time was an AMC salesman, is taking sides and in fact has an ax to grind against those responsible for the managerial mistakes that led to AMC’s demise. He does not spare the rod in his criticism of Roy Abernethy’s confused leadership, and, just as vehemently, fingers the workers’ collective as a destructive, mean-spirited, “greedy, shortsighted union . . . out for anything they could get.” “The militant, all-for-us attitude the Kenosha local had shown so many times was still in play.” “Down in Toledo union members [helped to destroy the company] with acts of vandalism, damaging Jeep vehicles, denting bodies, and pouring sugar in fuel tanks to render the Jeeps useless. It was a shameful and cowardly reaction to the very real and perilous situation AMC was in.”

Not much left to the imagination with bold statements like that!

There are many observational details pointed out in picture captions about rare, low-run, and show car vehicles. Here and there Foster uses the same information in the text as he does in a picture caption, but generally the picture captions expand on or elaborate on points made in the text. The graphic design and use of color are good throughout the book, but use of color behind the text at the beginning of each chapter can sometimes be hard to read for a partially color-blind guy like myself. The usual computer and statistical typos pop up here and there, for example: “For the year AMC sold a total of 391,769 vehicles . . . . Total sales volume was $4,039,901.” Really? That would mean that each car sold for a mere $10.31!

Statistical typos aside, this book does its job. The author mentions that he was “best friends” with AMC chief designers Dick Teague, Vince Geraci and Bob Nixon, so his descriptions of all the styling changes and how they were grafted onto existing platforms are informative and interesting. But more than just clever styling is required to sell cars, and AMC lacked a clear strategy on how it wanted to be perceived by the public. As Foster so brutally puts it, by 1969 the Rambler name had come to represent “at best, a low-bucks economy car; at worst, a cheap ride for losers.” An image, Foster points out, that was a direct result of bad management decisions.

The opening Introduction tells the reader to expect a book written by a strident defender of what could, or should, have been. To author Foster, AMC represents a culture that died needlessly, taking with it a unique corporate individualism that will never again walk this earth. In his words, “For many of us the sadness still lingers.” Following the Introduction are 10 emotionally charged chapters that take us on an up-and-down economic roller coaster ride through the good and bad times that consistently dogged AMC from 1954 until its death in 1987. Each chapter chronologically covers a multi-year time span. For example, Chapter Three, “1958–1963: The Rambler Takes Off” is followed by Chapter Four, “1964–1967: Things Go Wrong.” The up-and-down pattern continues until the end with Chapter Nine, “1983–1984: The Comeback,” followed by Chapter Ten, “1985–1987: The Final Struggle.” A four-page Index closes the book.

The death of AMC reminds me of a line from Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. When asked how he went bankrupt, the character responds, “Gradually, then suddenly.” That pretty much sums up AMC’s fate! In hindsight, it’s obvious that large car companies have always absorbed small car companies; it’s no different today. And also, just like today, AMC’s 1950s plan to build all their car models off a single platform to cut costs and stay competitive has become the “new” standard for efficient mass production. It is truly a shame that smaller car companies like Rambler, Nash and Hudson, or, for example, at the expensive end of the current marketplace, Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Ferrari and Bugatti, have all been absorbed by the corporate giants that rule the industry these days. All for the better, no doubt, but unfortunate nonetheless, and downright painful for Mr. Foster.

Copyright 2014, Bill Ingalls (SpeedReaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter