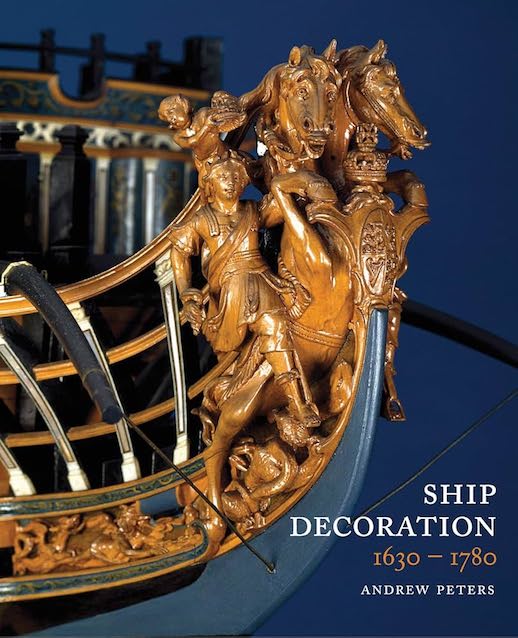

Ship Decoration 1630–1780

by Andrew Peters

by Andrew Peters

“The approaching ship turned out to be the 56-gun Apollon belonging to the French navy but fitted out as a privateer; she carried no colors. It was not until the vessel was fast approaching that she yawed slightly revealing decorations on her quarter gallery which immediately identified her as French.

In the confusion that followed, the British captain ordered the foresail to be set, which had the unfortunate effect of burying the gun ports of the leeward lower deck into the sea, causing the ship to take on a considerable amount of water.

The Apollon poured fire onto the Anglesea, leaving 60 men dead or wounded.”

The British captain and the ship’s master died on the scene and the poor fellow who had to assume command was court-martialed—and shot. The thing to take away from this vignette is that the French ship was recognizable even at a distance as French, not because it had “Je suis français” painted on it but by its decoration.

Cathead? Upper cheek? Bumpkin? Cagouille? Should that lion’s mane be flowing or curled? If, when you watch your pirate movies, one ship looks like another, this book will be an eye-opener. Who better than a proper ship-carver to write a book examining and comparing just this sort of detail? Back in the day, all the big seafaring nations had entire sculpture academies devoted to professional training in this craft but Peters who went into business full-time in 1990 had a much harder time “carving out” his place in that world on his own.

Cathead? Upper cheek? Bumpkin? Cagouille? Should that lion’s mane be flowing or curled? If, when you watch your pirate movies, one ship looks like another, this book will be an eye-opener. Who better than a proper ship-carver to write a book examining and comparing just this sort of detail? Back in the day, all the big seafaring nations had entire sculpture academies devoted to professional training in this craft but Peters who went into business full-time in 1990 had a much harder time “carving out” his place in that world on his own.

If you think about it, ship carving is about much more than whittling wood; it is a form of branding and Peters begins his book by explaining that “the primary function of a ship of war is to present military power, and through continued development it takes the most efficient form to achieve this. When decoration was applied to such a vessel, it was for the purpose of presenting an overwhelming sense of indomitable strength.” Ships of war are usually followed by ships of trade, and here too the goal was to present a sense of might and accomplishment. In fact, the fellow who carved the aforementioned Apollon was not only a painter and art theorist but also Director of the Paris Académie des Beaux-Arts and thus in charge of all aspects of Louis XIVs entire court style, from the Louvre to Versailles.

If you think about it, ship carving is about much more than whittling wood; it is a form of branding and Peters begins his book by explaining that “the primary function of a ship of war is to present military power, and through continued development it takes the most efficient form to achieve this. When decoration was applied to such a vessel, it was for the purpose of presenting an overwhelming sense of indomitable strength.” Ships of war are usually followed by ships of trade, and here too the goal was to present a sense of might and accomplishment. In fact, the fellow who carved the aforementioned Apollon was not only a painter and art theorist but also Director of the Paris Académie des Beaux-Arts and thus in charge of all aspects of Louis XIVs entire court style, from the Louvre to Versailles.

Moreover, a ship-carver has to be cognizant of the functional aspects of his work, “to create art forms that are not vulnerable to damage through the maneuvers of anchoring, sailing, berthing, and so forth,” and that is also able to withstand the rigors of a working life at sea and constant exposure to extreme weather conditions.

As a practitioner, Peters knows that replicating historic examples is a good way to learn to internalize the designs, symbolism, and techniques. This book is not a how-to guide for the aspiring carver but a guided tour of the work of carvers from the five principal nations that traded with the West Indies: France, the Netherlands, Great Britain, Denmark and Sweden, each of which is covered in a separate chapter that also includes lists of carvers and, in most cases, a color section. Drawings, models, and photos of surviving work and restoration projects illustrate the story in exhaustive detail.

Peters has the distinction of being appointed the sole carver on two important restoration projects, the French Hermione of 1779 and the Swedish Götheborg of 1738. The former is shown in some detail here in finished form but to the latter is devoted the entire Part III and goes into great detail regarding both the research and the work in progress.

The book begins with a Glossary and the terms explained there are not included in the quite substantial General Index. The Bibliography references a number of classic sources but mostly points to more recent work that should be easy to find for those who want to dig deeper.

The “Brief History of the East India Companies” (which includes Austria in addition to the five nations mentioned before) that makes up Part I is a nice summary of seafaring activities, political stance, and trade relations between Christian and Muslim realms. Readers new to the subject may well be surprised to learn, for instance, that “Algerines and other North African corsairs, generally known as Barbary Pirates” from the 1600s on didn’t just raid ships in their waters but sailed themselves all the way to England to take thousands of Westerners into slavery!

Not cheap, but a very fine book and of the usual high quality that marks this publisher’s titles.

Copyright 2015, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter