The Last of the Cape Horners

Firsthand Accounts from the Final Days of the Commercial Tall Ships

Edited by Spencer Apollonio

Edited by Spencer Apollonio

It had been sitting on the nightstand awaiting its turn to share what, indeed, turned out to be all that a narrative of the high seas ought to be. While its reader, your commentator, has enjoyed being out for pleasure sails, including on an 118-foot, hand-constructed replica of a two-masted Revolutionary War-era schooner or tall ship, that’s nearly the extent of my sailing experiences. By contrast the late Paula Murphy, racecar driver extraordinaire, certainly was the antithesis. She learned from her dad, who built sailing vessels from scratch in his “off hours.” Thus she handily won sailing competitions while but a lass in Ohio.

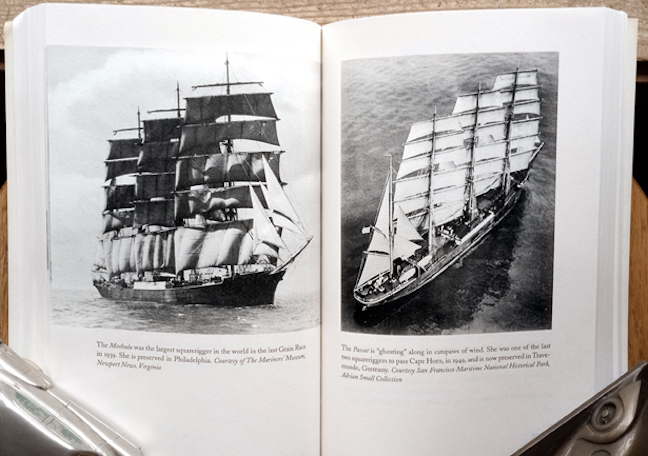

Though published nearly a quarter century ago by which time the few Cape Horn tall ships remaining were afloat to serve tourists or museum-goers, this book’s editor obviously considered that some of his readers may be less knowledgeable of sailing—and especially tall ship—vernacular so ‘twas good to be able to refer to the most helpful, nearly a dozen-page glossary from time to time. The English seemed quite clear when describing fore-and-aft rigging versus square rigging, but it was good to be able to confirm in the glossary that my perception based on the language was correct.

Then, as I read it was with ever growing admiration for the writings editor Spencer Apollonio had found and included; pithy, informative, sometimes frightening as when a man describes his climb and experiences aloft or being on deck with high seas sweeping that deck nearly clear of anything or anyone; or the daily life of “being clad in sodden clothes, sleeping in a sodden bunk,” eating—or too often not—the “unappetizing,” (at best) food. The challenges of daily life on a tall ship.

Other chapters do offer some of the “romance of the high seas” as again editor Apollonio, a sailor himself although that wasn’t how he earned his living, has found and shared some of the most charming and lyrically written reminiscences from those who had risked all to endure the frustrations of the no-wind doldrums bookended by some of the riskiest of high seas and winds. Then too, as ships had to dip ever more southerly, there were those waters well-populated with icebergs afore finally a ship rounded that southernmost part of South America off the rocky point at the tip of Chile’s Tierra del Fuego peninsula.

There’s a bittersweet but charming story of encountering an enormous flock of migrating swallows while far from land. Many of them, exhausted, found places to cling to the tall ship as their less exhausted flockmates continued on. “The resting swallows remained . . . gathering strength for a renewed flight. . . At breakfast that morning an inquisitive band of them startled and delighted the afterguard by flying through the open portholes into the messroom, where they fluttered and twittered excitedly about us, came to rest on our heads and shoulders and, gaining confidence, finally explored our victuals on the table. . . One, less cautious, landed feet first in the butter dish, another tugged at a piece of toast, trying desperately to share it with the captain.”

One writer briefly—but effectively—described the magnetisms of the sea-going life, “There is much about this beautiful Queen of the Seas—the thrill as she answered to the touch of my hand on her helm; the sheer joy of sailing before a stiff breeze; the majesty of the balmy tropical nights; the excitement of the battles against the elements; the risks and dangers and hardships; all this mixture of emotions and conditions, intermingled and following upon each other in unexpected and surprising succession. . . I think I can understand why men of the sea love it and their ships; also why they hate it and curse it; . . . why they leave it but keep coming back to it . . . why those who do leave the sea . . . again go down to it and why those who stay ashore die of sheer loneliness . . . having given up their first love.”

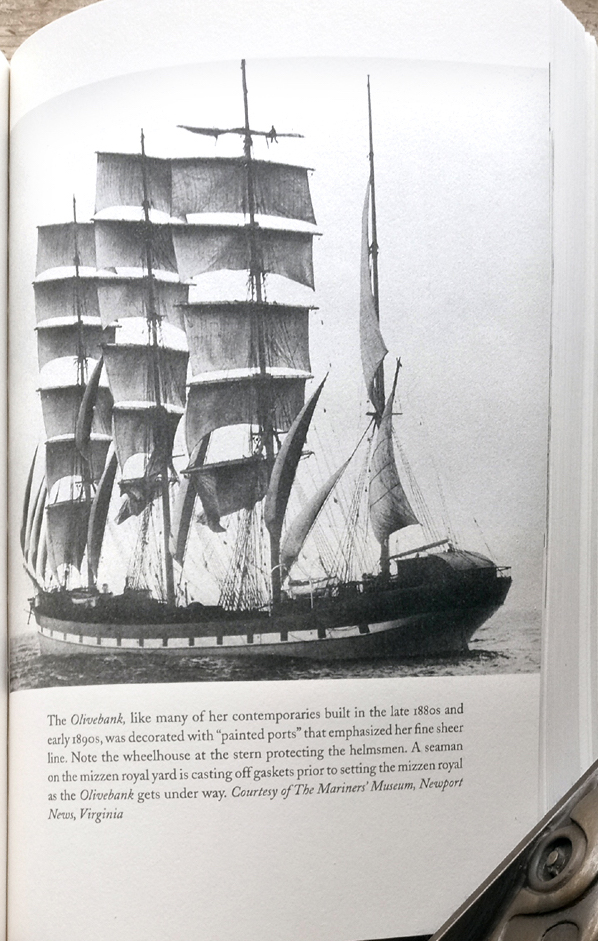

Writers tell of the ships on which each crewed. Those ships are all named along with a brief description of each in Appendix A. For instance, Olivebank, shown in an illustration above, is described thusly: “steel 4m bark, Built 1892, Glasgow, Scotland, 2,795 tons, 326.0 x 43.1 x 24.5. Sunk by a mine in the North Sea, 1939”

Writers tell of the ships on which each crewed. Those ships are all named along with a brief description of each in Appendix A. For instance, Olivebank, shown in an illustration above, is described thusly: “steel 4m bark, Built 1892, Glasgow, Scotland, 2,795 tons, 326.0 x 43.1 x 24.5. Sunk by a mine in the North Sea, 1939”

A lovely read incorporating the romance of the sea-going life in those magnificent tall ships while conveying the terrors and pleasures it entailed, mixed with clear explanations of many technical aspects of sailing such as this: “A main sail is a mighty spread . . . and may show to the wind as much as four thousand square feet of surface. . . Given a heavy press of wind, say twenty pounds to the square foot, and we have the sail urging [the] ship along to some purpose.”

Copyright 2024 Helen V Hutchings, SAH (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter