Jochen Rindt: The Story of a World Champion

by Heinz Prüller

In the Clermont-Ferrand paddock during the French Grand Prix meeting of July 1970, Jochen Rindt sat with his fellow-Austrian, journalist Heinz Prüller, in the Firestone caravan. They had collaborated on a book four years earlier, and now that Rindt was romping away with the World Championship, they agreed to write another. Nine weeks later, Jochen was dead, killed at Monza during practice for the Italian Grand Prix. After seeking the approval of his widow Nina, Prüller went ahead with the book about the man who now held the unfortunate distinction of being motor racing’s only posthumous World Champion. Forty years on, David Tremayne’s 2010 in-depth biography of Rindt prompts one to pull Prüller’s book down from the shelf once more, and see if it has stood the test of time.

It cannot have been an easy task for Prüller to write his great friend’s story when the wound was so raw, any more than it was for Jackie Stewart to provide a foreword, a role he also performed for Tremayne. Here, Stewart writes at length about the only driver he would place alongside Jim Clark as being “truly great.” He recalls their famous duel at Silverstone in 1969 with genuine affection, and makes the telling observation that Rindt matured as a driver after his maiden Grand Prix win, at Watkins Glen the same year: “he had come away from the point of having to win races.”

Several features point to the book having been aimed at the man in the street, someone who would have been unfamiliar with Rindt until his final, dominant season, rather than the serious enthusiast. There is no index, just a perfunctory list of World Champions, and two-thirds of the text is devoted to the last two years of Rindt’s life, when he was very much the star at Lotus. This may indeed have helped the book enjoy such success; it was translated from German into both English (by Peter Easton) and French, and ran to several editions.

But the first third of the book is unappetizing, particularly when compared with the depth to which Tremayne delves into Rindt’s formative years and development as a driver. Perhaps Prüller’s 1966 book covered Rindt’s early days in more depth, but here they are dealt with in summary fashion. His three years at Cooper are covered in fewer than 25 paragraphs. Indeed, each of his 1965 Grands Prix receive no more than a sentence. Even the first time that Rindt led a World Championship race, amid the chaos and torrential rain of Spa the following year, warrants only a paragraph.

Things get much more interesting when we meet Nina. Prüller even knows what she charged Vogue for modelling assignments. “Jochen was quite impossible at twenty-two,” she tells him. “He tried to impress me with his money and his racing, but I made it clear I wasn’t interested in either.” A two-year estrangement ended when she was modelling in New York in January 1967, and Rindt was passing through on his way to Daytona. They married in early March, on his last race-free weekend.

The Lotus chapters make captivating reading. Prüller claims that Lotus chief Colin Chapman wanted Mario Andretti to lead the team in 1969, and only moved for Jochen when Mario decided to prioritize USAC. Rindt’s contract was not signed until May, having been negotiated by his manager, one Bernie Ecclestone, whose negotiating prowess even 40 years ago was second to none. Jochen tells Bernie, “If you had negotiated with Colin for another five minutes, he would probably have sold you his factory as well.”

There is just a hint of what another latter-day giant of the sport would prove capable. Ron Dennis, or Ronald as Prüller introduces him, was chief mechanic to Rindt at Cooper, and, claims the author, moved to Brabham at the behest of the driver: “Ron soon became of great help to Jack . . . “

Prüller has a special way with words, and of recording the observations of those around him. He describes Indianapolis thus: “To the Americans, because of its startlingly high prize money, its speeds and its accident-proneness, it signifies at one and the same time a gold mine, a cathedral and a sacrificial altar.” And this is Chapman, on how he copes with the unfortunate accident record of his cars: “When someone is killed in one of my cars, then I accept responsibility, but not blame . . . Unfortunately things do go wrong, not for reasons of negligence, but because of ignorance or human fallibility, both of which are virtually impossible to eliminate.”

Rindt’s sense of superiority over his fellow drivers—an essential part, surely, of a champion’s attitude—shines through. When Ecclestone tells him that the front row-sitting Matra of Johnny Servoz-Gavin will not last 80 laps around Monaco, Jochen replies, “. . . the Matra might last but Johnny won’t last,” and indeed the Frenchman clouted the chicane on the first lap and retired shortly afterwards. And at the race where driver and writer agreed to collaborate on the book, Rindt won the 1970 French Grand Prix by exploiting a weakness he perceived in Chris Amon, and “decided to drive in such a way as to demoralize him, psychologically speaking.”

Through that year, Rindt wrestled with conflicting emotions. His former Cooper team mate, Bruce McLaren, crashed fatally while testing at Goodwood, and his great friend Piers Courage was killed during the Dutch Grand Prix, yet this was where the Lotus 72 first came good and Rindt won from pole. He queried why he should suddenly be the beneficiary of good fortune, most notably when he only beat Jack Brabham at Brands Hatch because the Australian ran out of fuel on the last lap. Rindt had rarely enjoyed such luck in Formula One before, and now others were running out of luck altogether.

Prüller was perfectly placed to witness and record these conflicts, and he was in the Monza pit lane that dreadful day, recording his friend’s last words in English, and watching Ecclestone sprint from the pits to the accident scene, where, helpless, all he could do was pick up Jochen’s helmet.

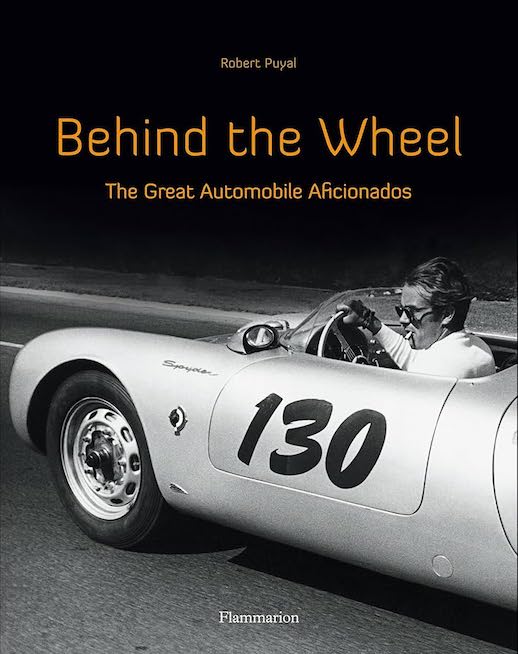

The book contains more than 40 black and white images, none earlier than 1964. Some of the racing shots are superb, none more so than Rindt in the Cooper Maserati, all four wheels off the ground at the Nürburgring. There are several photographs of Jochen and Nina. In the last one, he has his back to the camera and he is in silhouette, walking along a pier on Lake Geneva, Nina some way behind him. The image beneath it is of a grim-faced Graham Hill and Jack Brabham at Jochen’s funeral.

If you want to know about Jochen Rindt’s career in detail, go with Tremayne. If you want close, almost personal access to the triumph and tragedy of his last year, go with Prüller. This book has stood the test of time.

Copyright 2011, Paul Kenny (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter