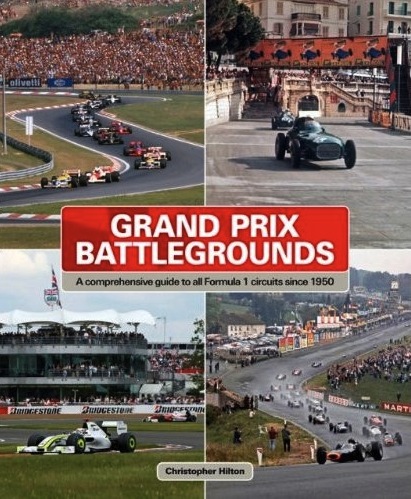

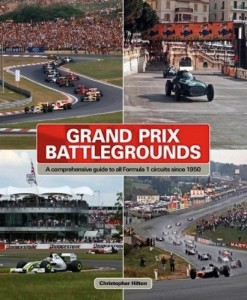

Grand Prix Battlegrounds: A Comprehensive Guide to All Formula 1 Circuits Since 1950

by Christopher Hilton

by Christopher Hilton

“The tifosi have been photographed carrying inflatable women into the circuit. Why? Again, it seemed to make them happy. The tunnel to the paddock was reputed to be very unsafe for all women, inflatable or otherwise. Having walked through it many times, I don’t believe a word of it, but myths don’t need truth do they?”

This well-thought out book will be another feather in motorsports writer Hilton’s already crowded cap. As the below quote shows, he isn’t just disgorging dates and facts and figures about the 66 circuits he covers but paints a picture. In this book he is your tour guide, and like every good tour guide, he can show you things even the locals don’t know.

If you frequented in recent years certain F1 websites or read magazines such as Motor Sport you would have come across an invitation to submit photos for this book.

Quite a number of people heeded the call and may find their images (all are attributed) here side by side with that of powerhouses such as LAT and the circuits’ own media offices. Hilton presents circuits from 28 countries on five continents that have staged Grands Prix between 1950 and 2009—820 at the time of the book’s writing. (Actually, Hilton reduces that count by the 11 Indy 500s between 1950 and 1960 which counted towards the Championship but had really nothing to do with it.)

A two-page annotated map of the globe precedes an introductory text that speaks to the differences between the “nature-hewn” tracks of old and the modern ones that are designed on computers and simulators by architects who must consider safety issues, physical forces acting on cars and drivers, environmental impact, FIA regulations, and—not least by any means—TV camera angles. German architect Hermann Tilke (b. 1954)—a racer himself—of Tilke Engineers, who has reengineered several older tracks and built many of the newest tracks from scratch, is referred to at length.

The circuits are presented in alphabetical order of country and within that by (the English rendition of their) circuit name. The only possible confusion with this approach would be circuits that changed their name. For each circuit, its location, date of construction (or, in the case of road circuits, date of first use), and number of Championship GPs is stated; a two-dimensional track map (old and new, where applicable) shows start/finish, race direction, and names all straights and turns; and its basic history is told in the form of fact and anecdote. The quote at the top of this review would have come from that section and the point here is not just to relate the vital stats of any one circuit but to describe its unique flavor.

Various other elements are also common to all treatments, and they are utterly unique to this book: a “Cockpit View” by one or more drivers gives their driving impressions; an “Eyewitness” account captures the impressions of, most often, a spectator; “Memories and Milestones” presents in narrative form and divided by years highlights such as pole, incidents, winners, fastest lap (also expressed in relation to the previous year’s lap, thus allowing apple-to-apple comparisons—to the extent that rule or track changes lend themselves to it) etc.; and “Facts of the Matter” which presents in tabular form statistics such as circuit length in miles/kilometers, winner/car by year, and fastest lap/pole. Statistician David Hayhoe (author of the Grand Prix Data Book 1950–2005, Haynes) is credited with furnishing and checking data for that element.

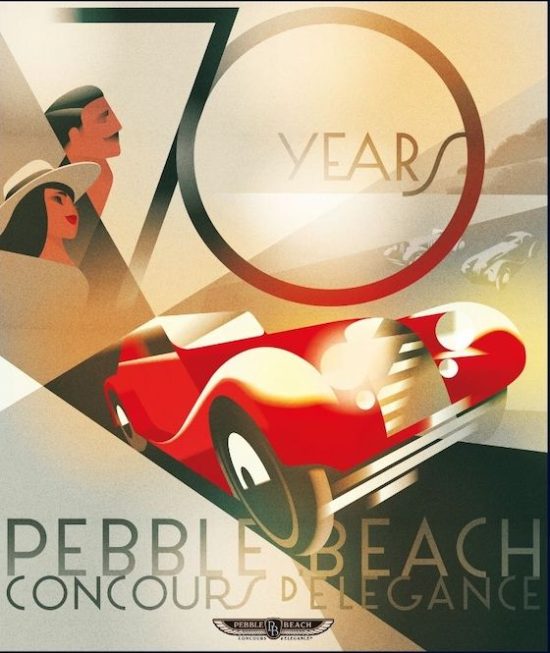

The hundreds of photos, mostly color, are augmented by the occasional race poster or program and newspaper clipping. The endpapers, incidentally, reproduce 64 different race posters. Several circuits also show a small track map with handwritten gear changes and autographed/dated by mostly Ayrton Senna or Nelson Piquet. A very few of these contain dedications or comments by them but between the small size of the reproduction and the handwriting they are hard to decipher. Excellent paper stock and photo reproduction, and nicely designed (most photos have rounded edges—to give them that “photo album” look?).

Since the purpose of the photos is to give a sense of the circuits, the depth of field is such that whatever cars are depicted are of necessity nothing but specs in the landscape. This, then, makes it often pointless when a photo caption, for instance, refers to a car by its race number but the car is all of a quarter of an inch long in the photo. (Better have a loupe at hand!) Still, it’s the right idea—better too much detail than not enough. Could the photos have been bigger? Sure! Would the book have then been more expensive? Sure!

There are, however, too few aerial views! This book is all about racetracks, and if we know anything, it’s that racetracks are generally not flat and level. A marvelous addition to this book, but probably not cheap to do, would have been the rendering of topographical maps that would convey at least a semblance of the elevation changes and possibly even the surrounding landscape so as to get a sense for drivers’ sightlines (for the latter see, for instance, Joe Saward’s The World Atlas of Motor Racing, 1989).

Appended are various tables that gather and reshuffle some of the key data that was scattered throughout the text and also show new bits such as laps per race/season, most races by country etc. Addresses and contact info is given for tracks still in use, and there is a Bibliography. For once we will not criticize the lack of an Index because this sort of book just does not lend itself to it.

Every time you watch a race you ought to have this book handy!

Copyright 2010, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter