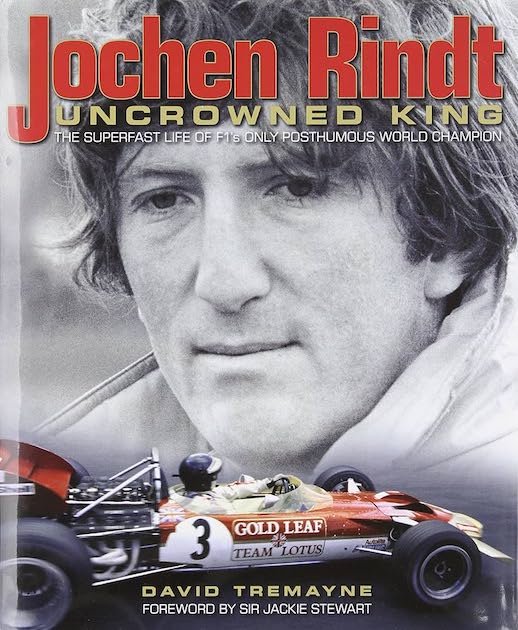

Jochen Rindt: Uncrowned King

by David Tremayne

by David Tremayne

“Who the hell is Jochen Rindt?”

That’s the title of the first chapter—because it was the first question people asked when Rindt seemingly came out of nowhere in 1964 to beat the big-name drivers of his day. And it is, the author fears, the first question a new generation of racing enthusiasts asks today. Even though he achieved so much in his few years of top-level racing, Rindt, by many called “the fastest man of his era,” died too young—in 1970, during practice for the Italian Grand Prix at Monza.

Heinz Prüller’s biography of German-born/Austrian-licensed racing driver Karl Jochen Rindt (b. 1942)—still, mercifully, the only man to be posthumously awarded the Formula One World Championship—was published within a year of his friend’s untimely death.

Alan Henry’s Autocourse profile was published 20 years later. So it was entirely appropriate for David Tremayne to mark the 40th anniversary of Rindt’s passing with a new book, not just, as he points out in his introduction, “to recapture his glories and perhaps to paint a sharper picture of his character and life, but also to put him into the true perspective in which he deserves to be remembered.”

Denied access to his subject, Tremayne is obliged to lift many of his Rindt quotes directly from Prüller, but he makes up for this by interviewing so many others who knew Rindt personally or professionally. They include his widow Nina and half-brother Uwe; Nick Goozee, the Brabham apprentice who worked on Rindt’s car when he burst on to the international scene at Crystal Palace in 1964; and modern-day giants of the sport like Bernie Ecclestone, Rindt’s manager for much of his career, and Ron Dennis, his chief mechanic at Cooper.

Tremayne has also been extremely thorough in his research of Rindt’s races, setting out not only his fastest practice time and grid position at a given meeting, but those of his team mate, and even pole time. Thus there is always context to judge Rindt’s progress at a given point in his career.

The book opens with a detailed account of Rindt’s remarkable arrival on the British F2 scene in May 1964—pole position and third place at Mallory Park, followed a day later by fastest lap and victory over Graham Hill at Crystal Palace. There follows an early insight into Rindt’s formative years: the deaths of his mother and father in the Allied bombing raids on Hamburg; the indulgent grandparents who raised him in Graz; and rapid progress on the track, first with Simca and Alfa Romeo saloons, then a Formula Junior Cooper. Thereafter, Tremayne eschews telling the final six years of Rindt’s life in strict chronological order, preferring to focus chapters on separate elements of his career. This works to best effect in the chapters on his unlikely win, alongside Masten Gregory, at Le Mans in 1965, and to his three unhappy visits to Indianapolis later that decade. Quite whether his exploits in F1 and F2 also needed to be recorded separately is another matter.

On one hand, this approach helps to highlight the strong contrast in fortunes encountered by Rindt in the two categories, with frequent, resounding success in F2, but failure and frustration in F1, through three years with a Cooper team in steep decline, via a 1968 campaign in which Brabham persevered a year too long with Repco engines, to a first season with Lotus which brought greater performance, but still more retirements. On the other hand, hopping back and forth between the years and catching fleeting glimpses of famous race weekends only fully described later becomes frustrating. This leads to such disconnects as finding Rindt using Indy prize money to buy furniture for the Paris apartment he has sold in the preceding chapter, and at its most clunky, we get this in Chapter 13, where Tremayne describes Rindt’s recovery from his 1969 Spanish Grand Prix shunt: “he went to Indianapolis to drive the Lotus 64 (see Chapter 8 ) and bounced back by winning the Formula 2 race at Zolder (see Chapter 10).”

Tremayne drops this compartmentalizing for the climactic 1970 season, and the final chapters thus make for a more satisfying read, rendered all the more poignant by our awareness that, for all the success and good fortune coming Rindt’s way once the Lotus 72 is functioning properly, we know that his luck will run out at Monza.

The reasons for the tense relationship between Rindt and Lotus chief Colin Chapman are fully explored. Rindt loathed the four-wheel-drive Lotus 63 and point-blank refused to drive it, and he was always concerned about the relative frailty of Chapman’s cars. Ecclestone’s summary of the driver’s career options for 1970—“you’ve got more chance of surviving with Brabham, but more chance of winning the championship with Lotus”—would prove sadly prophetic. Rindt’s more specific worry about 1969’s ever-larger rear wings was borne out by the dreadful accidents suffered by him and team mate Graham Hill at Barcelona, and resulted in the driver sending a blunt open letter to the motor racing press, demanding a ban on high-level wings. Tremayne quotes in full the letter, which does not appear in the English translation of Prüller’s book.

The question of Rindt’s alleged arrogance is also addressed. Those who unequivocally say he was big-headed include Ron Dennis and designer Robin Herd, who had talks with Rindt and Ecclestone about forming a team before opting instead to help set up March. Conversely, Ecclestone and most of Rindt’s mechanics have only the highest regard for him, sentiments echoed in Sir Jackie Stewart’s Foreword. Perhaps Chapman’s thoughts on Rindt’s personality, given originally to Prüller in the autumn of 1969, permit these contrasting views to be reconciled: “Jochen made it very difficult for me to get to know him, it took me almost a year. But once I knew him I discovered he had a heart of gold. He is so very, very blunt, but sincere and honest in all his opinions, and I have learned to respect this.”

Tremayne deals objectively with Rindt’s fatal accident and its possible causes. On balance, it appears that it was a broken front brakeshaft that speared his car into the barrier, and his refusal to wear crutch straps which caused him to slide forward in the cockpit, whereupon his own harness buckle caused the throat injuries that killed him.

Fascinating, irreconcilable opinions are offered on what Rindt would have done had he lived to enjoy his championship. They include immediate retirement and business partnership with Ecclestone; one more year with Lotus to fully exploit the financial opportunities open only to a world champion; and, outlandish though it may seem, an immediate move to NASCAR!

With his Postscript, Tremayne should have drawn together all the threads and completed his task of putting his subject into “true perspective.” What is Rindt’s proper place in motor racing’s pantheon? Above or below Villeneuve? Instead, the Postscript is a peculiar affair, recording what became of some of the supporting cast in the Jochen Rindt story. No mention of Chapman, or the man who ran Cooper throughout the Rindt years, Roy Salvadori, yet a quick resume not only of what Ecclestone and Dennis went on to achieve, but also an update on the careers of no fewer than seven writers. More than sixty paragraphs pass before Nina is mentioned.

Haynes gives the book the same large-format, glossy-page, heavily illustrated treatment provided to Tremayne’s previous book, The Lost Generation, and many of the photographs are superb. An early image of the infant Jochen makes it clear that if the explanation he gave Jack Brabham for his distinctive nose is true—a skiing collision with a tree—then he must have skied before he could walk! The numerous close-ups of the ruggedly handsome driver in open-face helmet makes one realize that, for all the safety benefits of helmet evolution over the last 40 years, a wonderful photo opportunity is denied the cameramen of today’s pit lanes. And there are touching shots, also, of Jochen with Nina.

A very detailed Index, and David Hayhoe’s authoritative tables summarizing Rindt’s every race, will ensure that the book is taken down from the shelf for many years to come. For this is a book worthy of inclusion in any motor racing library. With more thought to structure and more rigorous editing, it would have been better still. As it is, if there is room on your shelves for only one Jochen Rindt book, make it this one.

A Postscript from many years after this book first came out and was reviewed here: the publisher is no longer in business, and although there are other ones to carry the torch, especially Evro who took over some of Haynes’ list—as well as their editorial director—it is sad to look at Haynes’ high-quality output today and know that it wasn’t enough to save them. Moral? Support publishers!

Copyright 2026, Paul Kenny (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Thank you for this wonderfull review!