The Forbidden Bugatti Authentication Handbook

by Claude Teisen-Simony

by Claude Teisen-Simony

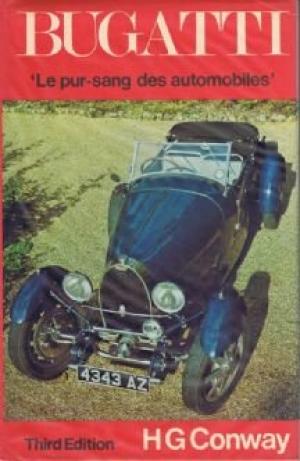

“Any ignorant fool can declare a Bugatti a fake, but it takes a serious Bugatti numbering expert to verify an original Bugatti.

The stimulus to write this book and my personal passion with Bugatti numbering started when I located an unidentified Bugatti Type 37. I found it, partly dismantled, in a corner of a Swedish warehouse. Nobody knew which car it was, though a number of English experts had inspected it.”

Fast forward: clues are analyzed, an identity emerges (chassis 37246), the argument is accepted as a plausible thought exercise—but the actual physical car is dismissed “by many Bugatti experts” as a fake. It requires monumental effort to get a definitive ruling from the British marque club, many toes get stepped on; this book is as much a reckoning as an attempt to codify the process of authenticating important cars.

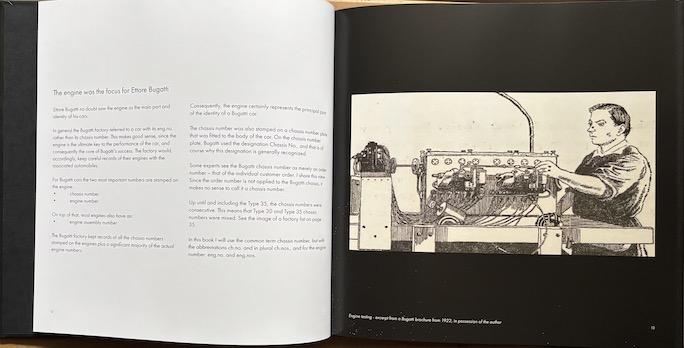

A lovely illustration from a 1922 Bugatti brochure.

That chassis referenced above was the author’s second Bugatti and he would go on to own many more, both complete cars and restoration projects. It follows, then, that over the decades of working on cars he had to become adept at identifying them and their constituent parts. In the interest of full disclosure, you reviewer’s appreciation of this particular marque is rather more hands-off but nonetheless enthusiastic, having been attuned by a spirited ride in a Type 23 to the finer points of its renowned gear-changing mechanism. Another peripheral note: the book’s author is based in Denmark and the publisher in Sweden, by which we mean to excuse the occasionally peculiar use of English.

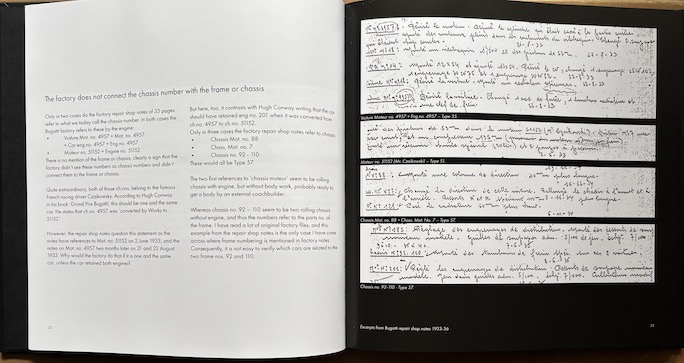

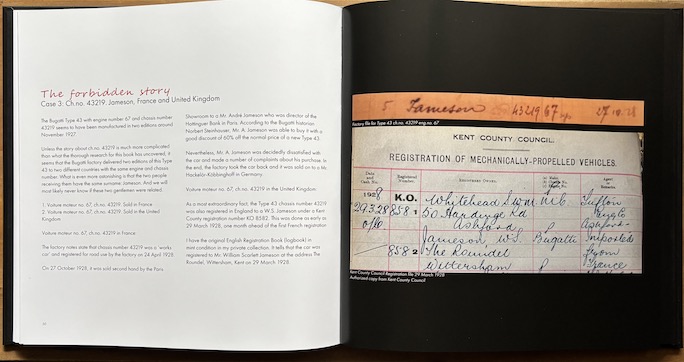

Teisen-Simony’s approach is to reproduce, on the right-hand page, relevant images, and his text on the opposite page. This may take the form of, for example, an original document such as a hand-written Bugatti Repair Shop note (in French) or a page from a British Registration Book on one side, with relevant bits highlighted by the author, and then his remarks (and translation) or narrative on the other.

This is what Bugatti Repair Shop notes look like.

While also relating points of wider interest the core of the book is hyper-focused on Bugatti arcana. The author discusses in detail five chassis with which he has had personal contact. To each is assigned a Case Number. As this is not a straightforward book to explain, we will deviate from our normal procedure of not re-telling the contents of a book and instead describe the cases so as to better illustrate what the concerns are:

CASE 1 deals with one of the most highly esteemed models, a Type 43, the 2.3L supercharged straight-eight. Chassis 43291 went to King Leopold III of Belgium, and through two metamorphoses that number was retained through Bugatti works rebuilds, when the chassis and engines were sold on as other identities between 1930 and 1933. Why?

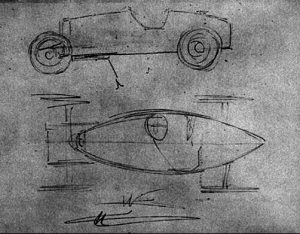

CASE 2 deals with one of the aerofoil “tank” Type 32s that went to the Czechoslovakian racing couple, Elizabeth and Vincent Junek. It underwent three chassis and engine changes while retaining number 4059, allegedly to avoid tax, and by 1925 became one of the first of the immortal Type 35s which had caused a sensation at its introduction at the 1924 French Grand Prix. Ettore Bugatti enclosed his sketch of what would become the Type 35 with his letter to the Juneks, offering them a 10% discount from the list price of 100,000 francs, which converts to $5,541, ca. $102,000 in today’s money—even if you factor in a century’s worth of care and feeding, that’s one good investment!

CASE 2 deals with one of the aerofoil “tank” Type 32s that went to the Czechoslovakian racing couple, Elizabeth and Vincent Junek. It underwent three chassis and engine changes while retaining number 4059, allegedly to avoid tax, and by 1925 became one of the first of the immortal Type 35s which had caused a sensation at its introduction at the 1924 French Grand Prix. Ettore Bugatti enclosed his sketch of what would become the Type 35 with his letter to the Juneks, offering them a 10% discount from the list price of 100,000 francs, which converts to $5,541, ca. $102,000 in today’s money—even if you factor in a century’s worth of care and feeding, that’s one good investment!

CASE 3 is even more convoluted. Type 43, chassis 43219, is recorded as sold and delivered twice: to M. André Jameson in Paris in October 1928, and to William Jameson (of the Irish whiskey family and a Royal Navy Admiral) in England in March 1928. This Jameson had a serious accident in 1938, and the car was destroyed, the remains being stored in his garage. Teisen-Simony writes that a friend of a friend has engine #67, perhaps from 43219. The perfect condition of the Kent County Registration Book in the author’s possession led to the American Bugatti Club’s refusal to publish this Case in their club magazine Pur Sang even though Cases 1 and 2 had already been approved and published there.

CASE 4 is a Type 57, the 3.3L twin-camshaft design that powered so many glorious bodies of the late 1930s. Chassis 57421 was a Works demonstrator with Galibier four-door sedan body, sold in 1938 to be re-bodied by Gangloff and claimed to be the car in which racing driver Robert Benoist covered 182.638 kilometers in one hour at Montlhéry track in May 1939, although the Factory File shows chassis 57796C. 57421’s original engine 333 was changed to 58C, and this appears on the list of Works Bugattis moved to supposed safety at Bordeaux before the fall of France in 1940. This list notes engine numbers, not chassis. There is a bewildering plethora of numbers stamped on Bugatti chassis cross-members, engine bearers, gearboxes and axles, while even fenders may have stamps preserved by careful restorers’ grafting onto new sheet metal. (Examples, not from the book, are shown in a collage at the end of the review.)

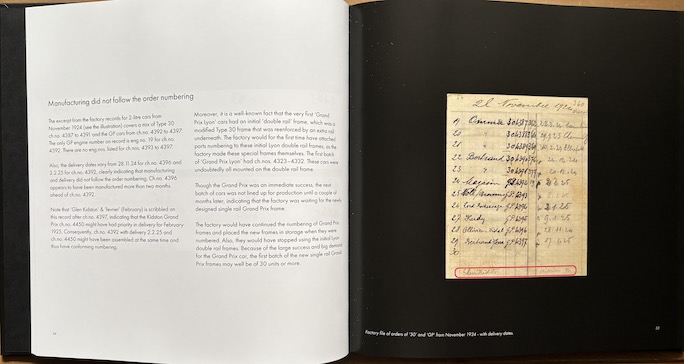

The heading of this section says it all: Manufacturing did not follow the order numbering.

A list of Type 13s, the Brescia, which M. Pracht, Bugatti’s treasurer, provided to Hugh Conway Sr., made references only to chassis numbers, not engines. Teisen-Simony quotes, however, “Registrar of the American Bugatti Club, the well-regarded US Bugatti expert Sandy Leith, provides an example with his statement: ‘The Factory notes for their competition cars always referred to the car as Voit. Mot. No. 5 not Chassis 54212. Voit. Mot. No. 5, the French abbreviation of Voiture Moteur, refers to Automobile Engine No. 5.’” The question here is how Bugatti engine production after forty-some years could reach only 5; this isn’t adequately explained. Perhaps the engine shop, faced with engines and no chassis, preferred these numbers?

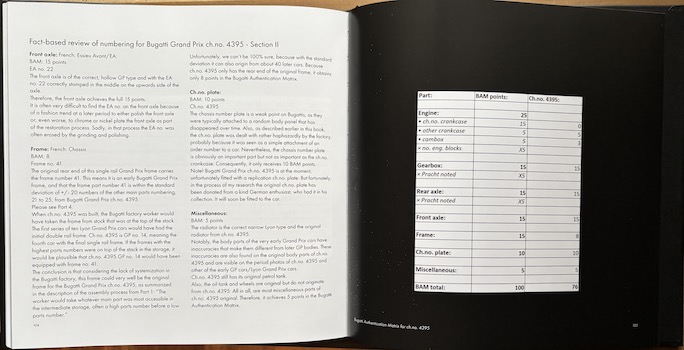

BAM points?? The Bugatti Authentication Matrix assigns point values to different aspects, the logic being that some things are more important than others in establishing originality. Any such methodology opens the proverbial can of worms because there is still case-by-case judgment required but there is no denying that anything is better than arbitrary whim.

A concrete example will help: “The original factory file for ch.no. 4392 to 4397 is shown in Part 1 of this book. It only lists eng.no. 19 for ch.no. 4392, whereas it has no listing of engine numbers for ch.no. 4393 to 4397. Consequently, ch.no. 4395 might never have had an eng.no. applied. In the Pracht factory files there is no eng.no. 108 related to any Grand Prix car delivery, indicating that this original cam box may have been supplied as a spare for ch.no. 4395 by the factory back in period. Cam box no. 108 is out of sequence with the other numbering, thus it gets 3 sub points out of 5. All in all, the engine only gets 8 points out of the total possible of 25 BAM points.”

CASE 5 concerns two Type 43s, 43235 and 43260, engines 86 and 98. These engines were fitted to 43281 and 43283 and sold. Teisen-Simony explains the storage stacking of chassis delivered from subcontractors, when the most accessible items taken for assembly may account for inconsistencies of numbers and dates.

The claim that “order numbers” became chassis numbers appears strange. On Page 45 the use of “frame” rather than “chassis” throws an extra curve since “frame” is the normal American usage. To quote the author again, “Confused? Then read on.” The Conclusion on that page reads, “For Ettore Bugatti, the most important parts were the engine, gearbox and rear axle—in that order.”

Here we enter the murky waters of replicas or fakes; call them what you will, there is a long history of new chassis being built, which is why the British-based Veteran Car Club, Vintage Sports-Car Club, and Bugatti Owners’ Club follow the “Three of Five Rule”: three of the five major components—engine, chassis, gearbox, front and rear axles—must be proven authentic. However, this has not always been adhered to either . . .

The French exchange rate to the Pound Sterling was very favorable if you were British, and so Bugattis were very popular there. They tended to lead hard lives, and their values rapidly depreciated so that modest budgets were stretched, with bits swapped around to keep cars mobile or improved. A very long time has elapsed since these cars were built, and the “trailer queens” we see today exist in another world even from the VSCC 50th Jubilee I remember forty years ago, when Grand Prix Bugattis were still being used to pop down to the pub for a pint.

When does a hobby become a hobbyhorse? Despite the large sums required to maintain these works of art, and even to have their authenticity established, to quote Rodney Smith, “Why can’t we all just get along?” To quote a crony, “This is all meant to be fun.”

Teisen-Simony mentions what he regards as a shadowy organization, the Bugatti Identification Group, whose acronym infers Big Business, Hedge Funds, Wealth Management, and other wielders of power. This group has not welcomed the book and its companion The Hidden Bugatti Diatto Alliance (to be reviewed separately), declining to review them despite the author’s earlier articles, which begat this book, having been published in Pur Sang.

Writing in a personal tone, the author fully engages with his readers, and his decades-long enthusiasm for these wonderful cars and their part in automotive culture is contagious. Whether or not you agree with his findings, the results of his research and involvement will surely stimulate further interest.

Copyright 2024, Tom King (speedreaders.info).

A random sampling of various numbers on Bugattis in New Zealand, not from the book, simply to illustrate what one would encounter in the field: engine bearer on a Type 57, Type 46 engine bearer on #46587, rear crossmember number 98, engine number 16s).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter