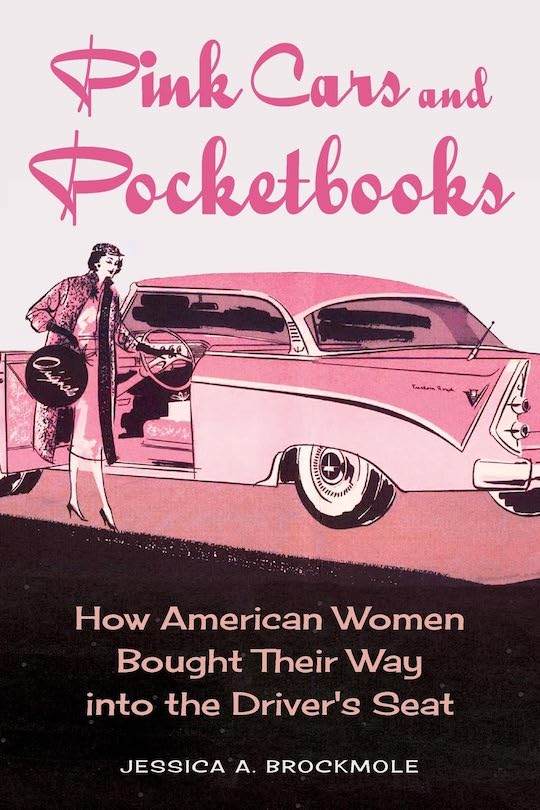

Pink Cars and Pocketbooks, How American Women Bought Their Way into the Driver’s Seat

by Jessica A. Brockmole

by Jessica A. Brockmole

“The auto industry . . . used gendered car ads to define an acceptable place for women in the automotive marketplace and to control how much influence they had in the industry.”

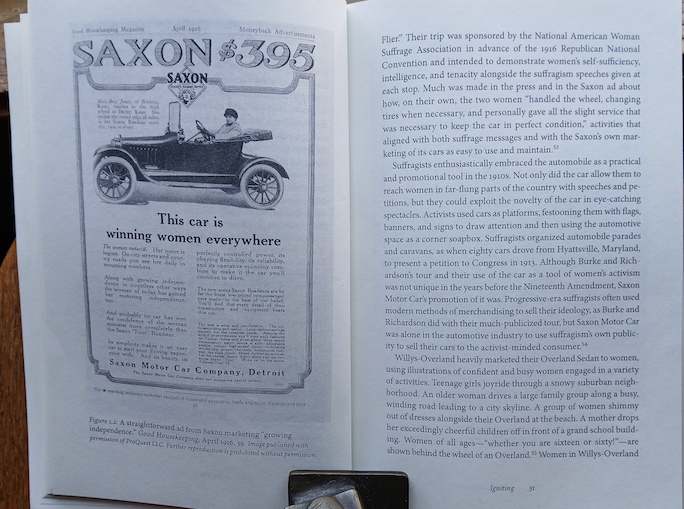

You wouldn’t be far off if you observed that some things done in the name of progress actually are backwards progress. Such a situation is described as this book begins with Jessica Brockmole, its author, observing “In the first two decades of the twentieth century automotive companies advertised to women.” She cites details and gives examples including a listing of those manufacturers and the magazines in which they placed ads. One of those ads is shown below.

This ad was reproduced from April 1916 issue of Good Housekeeping. Notable is the copy printed above the hood of the Saxon. It reads: “Miss Bess Jones, of Wichita, Kansas, teacher in the high school at Derby, Kansas. She makes the round trip 26 miles in her Saxon Roadster every day, rain or shine.”

Where and when that backward “progress” commenced was as other types of businesses formed, developing into services with each wanting a piece of the “pie” in exchange for their work. Businesses/services included advertising agencies to create and place ads structured based on the results of the advice of marketing research businesses. Ad placement companies had their opinions regarding where best to place those ads. Each added “layer” was another predominately male-dominated business as were the clients. As a result women’s real and serious interests and desires were marginalized and misrepresented in print ads (i.e. magazines and newspapers) for there were no televisions as yet.

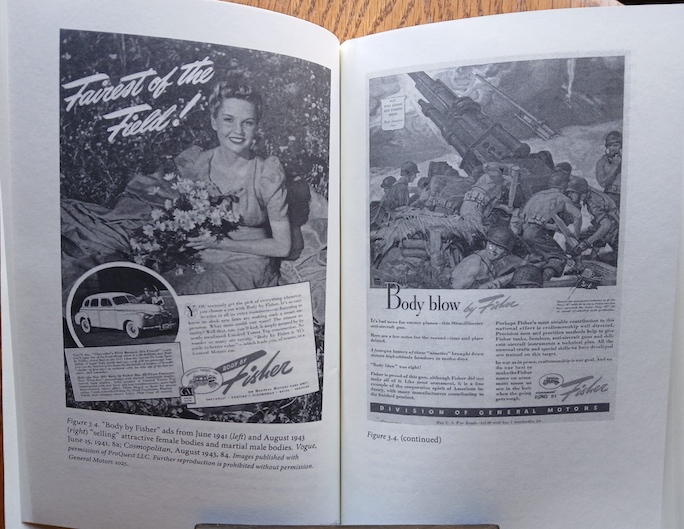

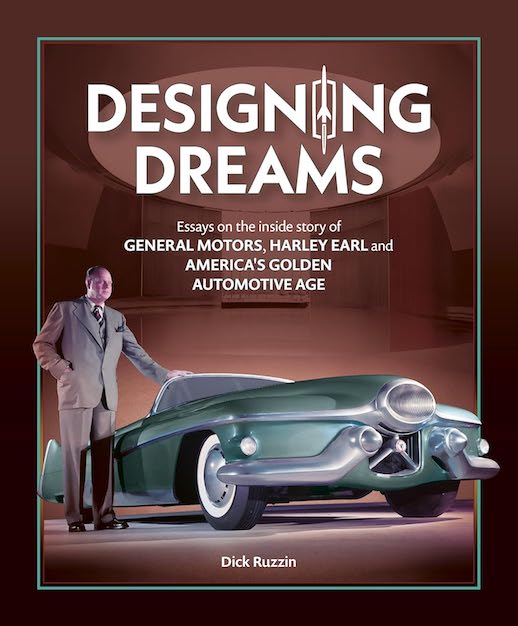

The author’s analysis of these two wartime ads from the Fisher Body division of General Motors includes a comment they were “ ‘selling’ attractive female bodies and martial male bodies” during this time when cars weren’t being produced, thus not sold.

Consider: reports of research results are only as worthwhile as their accuracy. If a research survey answer is: We’d appreciate “features like adjustable seats, steering wheels, and mirrors” but the “report indicated that women just looked for comfort and luxury”—well, you can see how the problem developed.

Sometimes best efforts backfire. Such an unintended consequence surrounded Dorothy Dignam who successfully created and placed ads for client Ford Motor Company 1935 to 1940. Her ads were spot-on but the marketing schemes she proposed—and she proposed a dizzying number of them—did not find favor and weren’t adopted. Yet ironically they fed and strengthened the misperception that women’s interests in cars were limited to color, style, living room-like upholstery fabrics and patterns and little else. Brockmole explains how it all played out as she introduces readers to Dignam, an interesting and talented lady working within the automotive industry pre-war when few did.

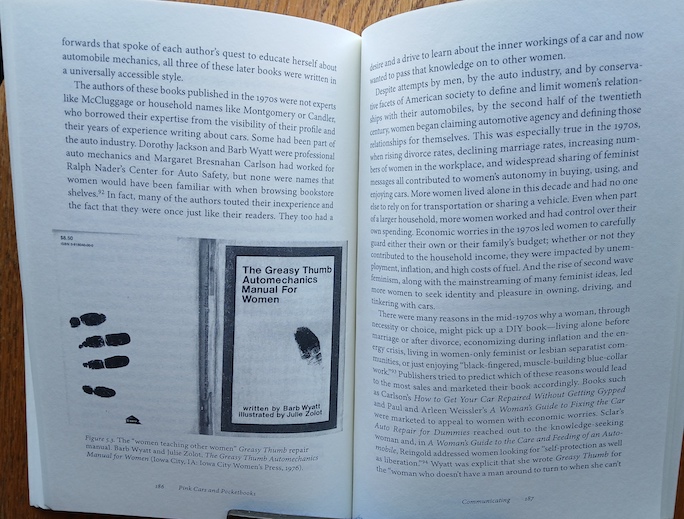

Brockmole takes her reader decade by decade sharing the understanding she gained as a result of her thorough research regarding “the interplay between advertising and society [and] the role of the consumer in this relationship . . . and gender.” She notes that as she followed women’s relationship with cars and automotive marketing she found “in the 1970s women took greater control of automotive messaging.” And she makes clear that she was “unable to find evidence either that the auto industry attempted to appeal to women of color or that they deliberately excluded them from their marketing efforts.”

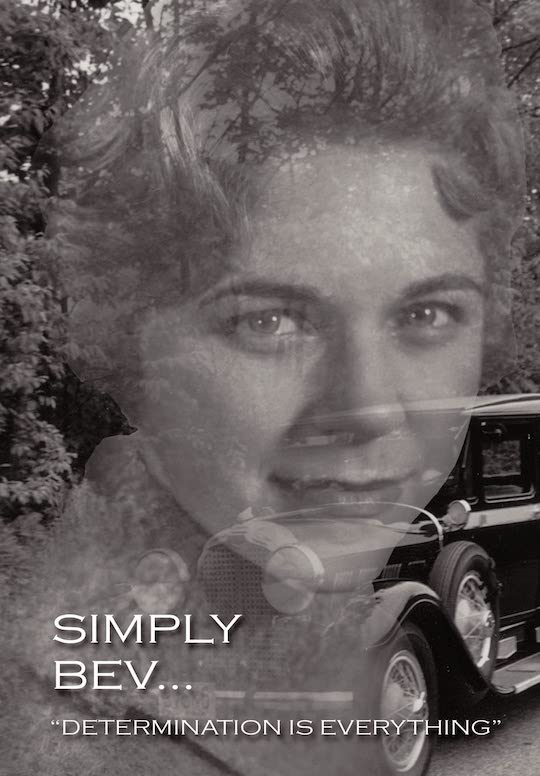

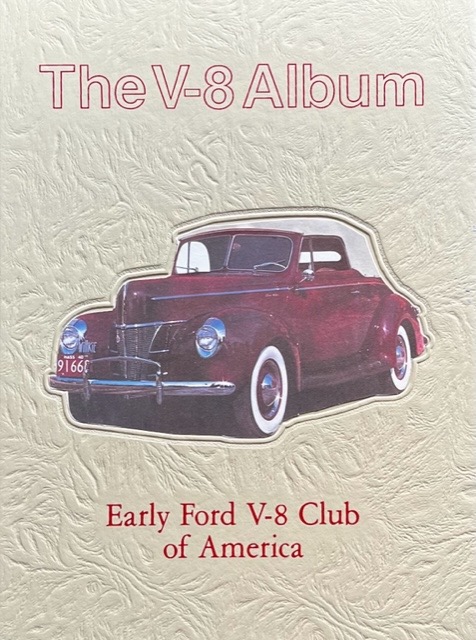

Image is of the front and back cover of a real and inexpensively produced book educating women on the inner workings of automobiles. Published in 1976 it “stands out as unexpectedly successful . . . it went through six printings” and “in 1985 . . . was still being reviewed and mentioned as a ‘classic’.”

The chapter titled “Conclusion” opens describing a 1924 ad paired with a 1976 as one with the overiding headline reading “Knowing what you wanted in 1924 helps us know what you want in 1976.” It’s another apt demonstration of advertising execs and their manufacturer clients still not “getting it.” The word “want” connotes selfish or self-centered desires. Far better—and more reflective of women’s interests—would have been instead of want “knowing what mattered to you” or “knowing what you valued” for then the emphasis could have correctly been on safety, convenience, ease of handling and the like rather than stylish inside and out and a pretty color!

Though fancifully titled, Brockmole’s writing—and her assessment of the auto industry—is clear and well-reasoned. It’s a thought provoking read even as she concludes opining “Despite women’s messy history with the automobile, they have claimed the knowledge, the voice, and the confidence to define that relationship for themselves.”

Copyright 2025 Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter