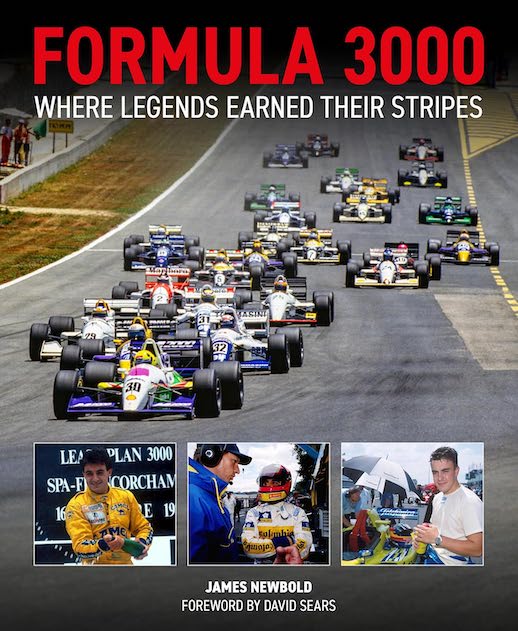

Formula 3000: Where Legends Earned Their Stripes

by James Newbold

by James Newbold

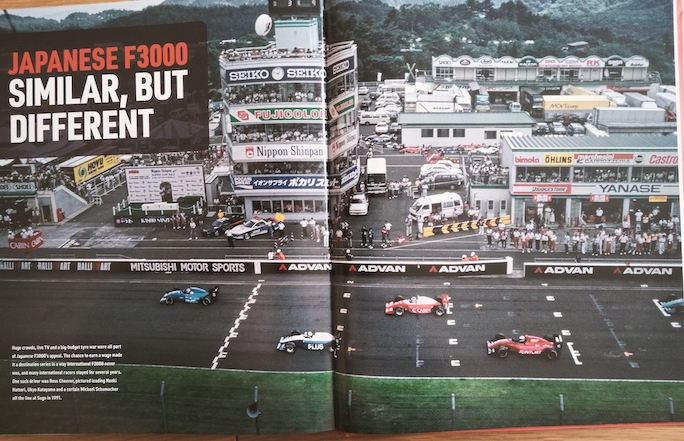

“We couldn’t stop as quick [as F1]and we couldn’t accelerate as fast, but the cars were so fabulous.”

—Andrew Gilbert-Scott, on Japanese F3000

Formula 2 had become a busted flush by 1984. Honda’s domination and escalating costs meant its appeal was waning and a refresh was urgently needed. Enter F3000 in 1985, enabled, inter alia, by the fact that Formula 1’s turbo habit had made the Cosworth DFV another busted flush.

F3000 became the series that launched the careers of a host of drivers, team managers and engineers who later shone in F1, WEC, and CART/Indycars. And it also created good business for manufacturers, notably Lola, March, Reynard, and Ralt. Books about F1 are two a penny (and that’s overpricing some of them) but F3000’s story hasn’t really been told until now.

This is James Newbold’s first book, so was his seven-year term at Autosport a good enough grounding to equip him for this overdue history of a much-loved series? With two relatively minor reservations, which I’ll come to later, the answer is yes.

This is a typical Evro heavyweight, its 416 pages and 350 color photographs thumping the scales down to 4.5 pounds. After a Foreword by F3000 stalwart David Sears (Supernova, Den Bla Avis teams) the author gives a detailed account of each season from 1985 (“Formula 3000 Finds Its Feet”) until 2004 (“End of an Era”) and also includes chapters on the domestic British, Italian/Euro, and Japanese F3000 series. Helpfully, there’s also an introduction and epilog which describe the key reasons for the formula’s ascent and decline in motorsport’s ever evolving eco-system.

From a 2025 perspective it seems extraordinary that, forty years ago, I could watch modern single-seaters compete in four or five separate formulae at UK circuits. At the apex was F3000, which offered brutally fast and noisy racing from what the French used to term les coming men (don’t Google this). I remember David Coulthard racing in a head-down, red mist fury at Silverstone in the early 1990s, the thunderous proximity of the Birmingham Super Prix, and the novelty of the Formula’s debut at Silverstone in 1985. And now? Formula 1 has sucked so much cash into its firmament that the only single-seater racing I can see in the UK, at least away from the Grand Prix hoopla, is the underwhelming Formula 4, boasting a Tatuus spec chassis and a wheezy little Fiat engine. Be still my beating heart . . .

This is what might be called a meat and potatoes book, with enough substance to sate even the hungriest reader. The seasonal reviews leave few facts unspared, whether on drivers, race cars, team shenanigans, circuits, or rule changes as well as the races themselves. It’s shocking to be reminded that the era of drivers like Moreno, Thackwell, and Capelli racing big-power single-seaters at Pau, Enna, Donington Park, and Brno is now as distant as the reign of the Alfa Romeo 158 and Maserati 4CL was when F3000 made its debut. Time’s winged chariot [1] must have been turbocharged, right?

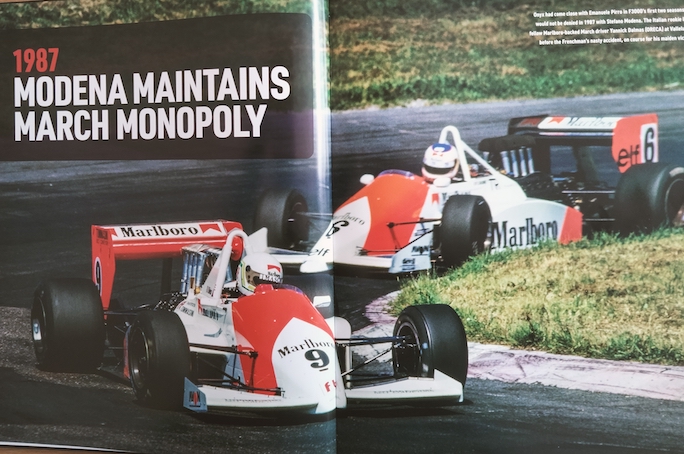

I saw the first F3000 race at Silverstone in 1985 and, as the author describes, the formula’s tentative first steps raised many questions. Would a repurposed F1 car work? No, it wouldn’t. Was the DFV the only show in town? It was for many years, until Mugen and Judd crashed the party. Would domestic F3000 series work? Not really, unless you were big in Japan. Would F3000 produce a new generation of F1 drivers? Well, sort of. A good F3000 career meant Grand Prix success for drivers including Fernando Alonso, Juan Pablo Montoya, Jean Alesi and Johnny Herbert, and drivers such as Kenny Brack, Gil de Ferran, and Tom Kristensen excelled at Indianapolis and Le Mans. But for many, or even most F3000 champions, success in the formula was to remain their peak achievement. There’s no shame in that, and it’s proof that so called junior formulae can be respected ends in themselves and not just the clichéd “stepping stone” to Formula One. Just ask Roberto Moreno and Stefano Modena, Ivan Capelli, or Ricardo Zonta.

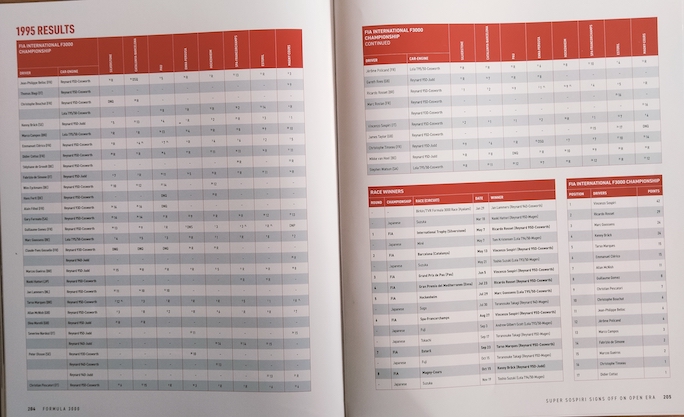

There is an enormous amount of information in this book and, apart from the 15–20 pages devoted to each season, there’s also enough statistics and results tables to chew over for days.

Each of the 369 drivers who competed in the formula is named, and there’s as much fun to be had in identifying the never-weres and no-hopers as the shoulda-woulda-couldas. Who remembers that Alex Albon’s Uncle Mark won a British F3000 race in 1992 at Snetterton? And there’s more, much more—most DNQs (19 for Jean-Pierre Frey and Jari Nurminen), most wins by engine (100 for Zytek Judd) and even longest points streaks (10 for Juan Pablo Montoya, 1998). As for the teams (or “squads” as they are often, and irritatingly, termed), there is no shortage of F30000 alumni in the motorsport firmament, none more so than the former Arden boss, Christian Horner (jobless at present but, y’know, watch this space?).

Like almost every other formula in the history of motorsport, F3000’s debut was greeted as the bright new dawn the sport needed. Formula 2—now so 1984—was consigned to the dustbin of history and everything was for the best in the best of all possible worlds. But, as Voltaire’s Candide found out, mindless optimism doesn’t stop the bad stuff happening—it almost invites it to do so. The author does an excellent job in describing F3000’s decline and fall. He describes how, even by 1994, the cracks were opening in F3000’s hegemony, with F3 an accepted stepping stone to F1, and even tin top DTM was burnishing CVs brightly enough to enable a driver to bypass F3000. There was retrenchment in 1996 by becoming a spec formula (good for Lola, bad for everyone else), and by 2003, F3000 was exclusively an F1 support act, whereupon F1 poached most of its sponsors. In 2004 it was in the last-chance saloon, superseded by the idiotically named GP2 in 2005. Which, in an unprecedented outbreak of common sense, became F2 in 2017.

So, what are the flies in the ointment? The first is the choice of photographs. At first glance they’re all just fine—lots of pin-sharp pictures of race cars and team guys looking like race team guys usually do. But, like Jutta Fausel’s recent book on Formula 2, there are too many tightly cropped images for my liking, and I’d have liked some more atmospheric shots of pit and paddock. A visual record of time and place adds more with each passing decade—look no further than Doug Nye’s magnificent The Last Eyewitness as proof.

The second is inevitable, and certainly not the author’s fault. This is a book of record and is the fruit of what must have been a phenomenal amount of research into a largely neglected subject. There’s plenty of insight and anecdote, and all that is lacking is the personal view of an author who experienced the rise and fall of F3000 at first hand. The inimitable Simon Arron reported on all but two of the 206 F3000 championship races and was described by David Sears as “. . . the biggest promoter of F3000 and drivers when he walked around the F1 paddock.” We lost Simon in 2022; and if he wasn’t the “last eyewitness” he certainly would have been the best.

- Andrew Marvell, 1681. Not an F3000 guy, as far as we know.

Copyright 2025, John Aston (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter