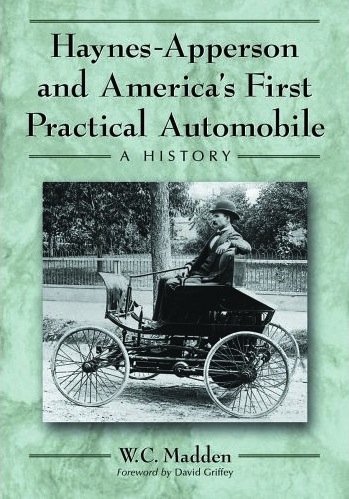

Haynes-Apperson and America’s First Practical Automobile: A History

by W.C. Madden

by W.C. Madden

Before you chalk the complex and relatively shortlived (1894–1925) motor manufacturing activities of the three separate companies—Haynes-Apperson Automobile Company, Haynes Automobile Company, and Apperson Brothers Automobile Company—off as ancient or marginal history, consider that one of the technologies it pioneered is in use still today: stellite. This cobalt-base alloy with chromium and other metals—very hard and used to make wear- and corrosion-resistant coatings—was patented by Elwood P. Haynes, the man who developed several new metal alloys that became critical for building sturdy car components.

The original 1894 Haynes-Apperson Company was only the second company in the United States to manufacture cars for sale to the public, approximately six months after the Duryea brothers formed the Duryea Motor Wagon Company in 1895. Where the early Duryea cars were unreliable and crude, the Haynes-Appersons were more substantial and functional, gaining in popularity while the Duryea product faded away to die in 1898. In general, Haynes cars appealed to conservative customers seeking reliability, and the Appersons appealed more to the marketplace interested in horsepower and speed. The Apperson brothers excelled at winning races while Elwood Haynes excelled at getting the attention of the demographic served by publications like Scientific American, which used a Haynes-Apperson car in a 1902 article on the current state of automotive design in the United States.

Both in terms of technical and business history this firm and its people are deserving of attention—and this book is the only one on the subject. All the harder then to say that it only skims the surface. It’s a point of departure more than a final word. Compiled from information gathered from company advertisements, newspaper/magazine articles, and museum information, it is short on detailed information on the cars themselves beyond that listed in sales pamphlets and promotional fliers, information which the text often enough merely repeats. It is, however, engagingly written and the wealth of period photos and ads is a strong draw.

The author has written and/or co-written several other books, most dealing with baseball and baseball history and statistics. Although definitely worth buying, this book suffers from too much sterile data gathering and not enough mechanical understanding, or “feel” for the subject matter. The author never takes us under the car or pops the hood to show us what made them tick mechanically. “Electric shifting on the steering wheel” is all we ever get to know about that exotic 1913 Haynes innovation. A solid beginning for a topic that deserves a second look by someone more simpatico with mechanical subject matter. Until that day arrives, consider this a worthwhile teaser to wet the appetite.

Copyright 2011, Bill Ingalls (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter