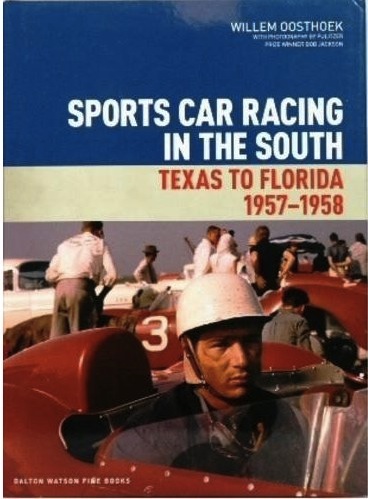

Sports Car Racing in the South: Texas to Florida, 1957–1958

by Willem Oosthoek

by Willem Oosthoek

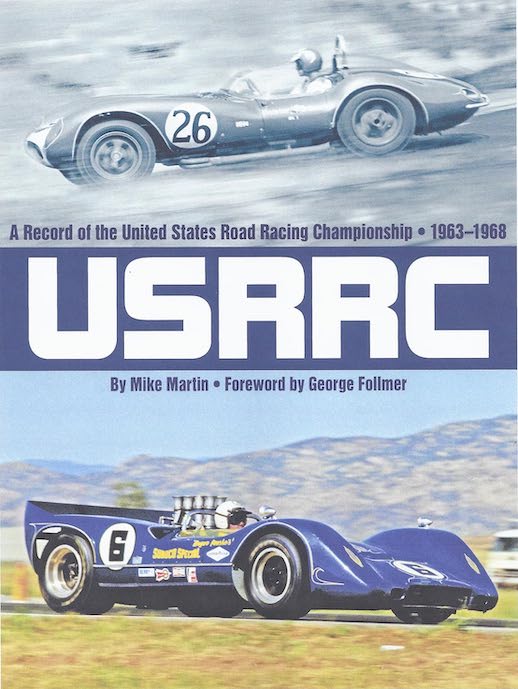

To the serious student of racing in the US, this book and its two future companions will be inevitable purchases. To the more casual reader it won’t be the hard data so much as the abundance of photos that will make this acquisition worthwhile.

The entire trilogy will encompass the years 1957 to 1963. The starting year is perhaps a bit arbitrary but Oosthoek pegs it as the year in which sports car racing in the South “surged,” fueled, as he rightly notes, by Texas and Oklahoma oil money. From then on proper, big-name racecars joined the home-built specials, and drivers began to attain regional and possibly national prominence. Both the machinery and the drivers, and the race venues themselves of course, will be more recognizable in the coming two volumes but you’ll not want to miss the first one.

The very fact that these early races were of mostly local relevance, often held for nothing more than the drivers’ or local community’s entertainment, is the reason period press coverage and record-keeping are so shoddy. Readers with an interest in this subject will obviously know Terry O’Neil’s books. Both authors were propelled into action by the same lack of reliable, cross-checked race data. In the case of Oosthoek, whose several painstakingly researched books on competition Maseratis (also by this publisher) have made him the recognized authority on that subject, the matter was of particular urgency because Maseratis on the auction market increasingly claimed implausible but difficult to refute race history from just these years to substantiate their ever rising asking prices.

Even compared to his own Maserati books, this new book attains new heights in terms of data mining and also organization. It’s one thing to “connect the dots” in an intelligent and verifiable way but it is another entirely to first of all find dots to then connect. Unless you have done this yourself you simply cannot fathom the vastness of the task of sourcing piles of magazines, race programs and Monday-after newspaper race results, and then compare the data, fill the gaps, spot and reconcile conflicts, and construct a correct paper trail. A name that may be mentioned in a race program may not show up in the reported results—did the driver drop out, did the race get cancelled, was s/he too unimportant to get written up, did only the top three get a mention? Endless, endless questions.

Oosthoek was able to interview 25 participants, just in the nick of time, as some of them did not live to see the finished book. Material from personal scrapbooks and diaries may not settle all questions but it adds insights and human interest to the text that statistics alone can’t convey. More importantly, this brought to light photos that had not been published before. These amateur photos augment the many professional ones by photojournalist Robert H “Bob” Jackson (whose name you may recognize as the 1964 Pulitzer winner for his photo of Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald being shot by Jack Ruby). There are also a number of race programs and ads.

Covered are 52 events in chronological order. Each race is introduced by Oosthoek’s commentary, accompanied by a uniform data set (Status, Sanction, Track Details, Crowd, Weather, Chief Starter, Entries, and Program), tables of select race results, and thoroughly captioned (and credited) photos. While the narrative touches upon all races from Novice to Featured, the results tables (race number, number of laps, race distance, number of starters, overall positions, car numbers, drivers, cars, class finish, completed laps, winner’s time, average speed) only list schedules for the modified races and not production classes. (Reasons are explained in the book.)

Each of the two seasons ends with a list of all identified chassis numbers (marque, model, driver/owner) in order of race appearance (Dick McGuire’s Monza is missing from the Ferrari list). Appended at the back of the book are lists of sources consulted and of interviewees, and a map. The Index is extraordinarily thorough.

For the purposes of this book, the “South” comprises the eight states of Florida, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico. The reader new to this era really should also look at Big Picture books about international racing in those days. FIA regulations would limit cars to three liters for the 1958 season which meant the previous season’s “big” cars trickled down the food chain. From the perspective of our modern “been there/done that” world it simply boggles the mind that there was a moment in time when the finest thoroughbred European race cars money could buy should all of a sudden be careening around a few hay bales on obscure American airfields in front of an audience that had probably never seen such exotica before.

Even if the race commentary and all the stats should not interest you, the photos alone offer hours of distraction—not least in the context of today’s stratospheric prices for many of the machines you see flung about here with great abandon! That photo reproduction and paper are of a high order is a foregone conclusion in a Dalton Watson book. Typographically there is a distinct 1950s flavor and the book is a generous 13˝ tall.

Oosthoek personally footed the bill for many of the photos. You can help take the sting out of that by buying the book directly from him [willemoosthoek@aol.com], which would also get you an autographed/personalized copy!

Copyright 2011, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Won the Society of Automotive Historians’ 2012 Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot Award.