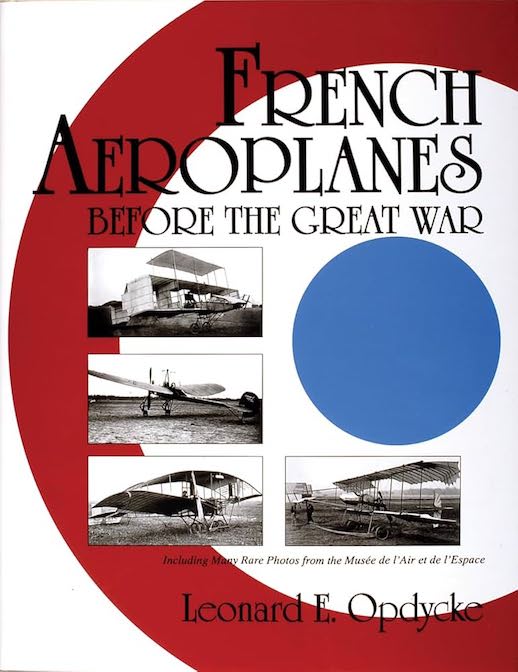

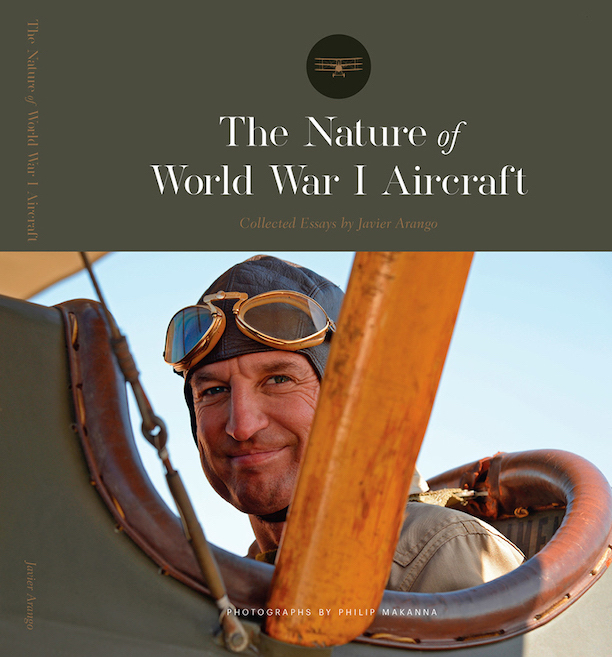

French Aeroplanes Before the Great War

by Leonard E. Opdycke

by Leonard E. Opdycke

“The period before World War I was an exciting one for aviation pioneers; anything seemed possible, and while in some cases the understanding of aerodynamics and structural engineering was minimal and its absence filled in with enthusiasm, in others it was surprisingly full.”

Some 700 French aircraft builders (and designers, pilots, and moneymen) gave it a shot in the technologically fertile but immature years before World War I. Since most of us probably struggle to name a dozen, many of these efforts obviously didn’t amount to more than a footnote in aviation history. Even so, they advanced the body of knowledge, as does this most useful book by recording them.

From Foreword to Appendices, this book is chock-full of arcane information you’ll not find conveniently, if at all, anywhere else. If the Foreword strikes you as uncommonly learned, you’d be right. It is by J.M. Bruce of whom one would expect nothing less—but about whom nothing is said! At the time Opdycke’s book was published, Jack Bruce was still alive (d. 2002) and introductions may have seemed superfluous. The trouble with that approach is that readers of subsequent generations will have no idea that Bruce (ISO, MA, FRHistS, FRAeS, Vice President of Cross and Cockade International) was one of the most respected WWI aviation historians of his day. Among his many published books is one of very similar scope, British Aeroplanes 1914–1918. Early-aviation buffs should make it a point to acquire what they can of his work! It is high praise indeed that the great man is calling the “size and scope [of Opdycke’s book] an enduring testimonial to the author’s endurance, determination, percipience and competence, quite as much as it is a worthy monument to so many who toiled with such dedication in the pre-1914 period to establish the foundation of aviation in Europe.”

Opdycke calls his book a “catalog,” which in terms of structure is quite a different thing than an “encyclopedia.” The book is divided into two parts, Part 1—all of ten pages—offering a chronological overview of 16 key pioneers 1678–1888 and Part II the aircraft (including rotor wing) in alphabetical order. The length of the entries naturally varies depending on what lo these many years later can still be unearthed about various makers. Some entries are, literally, one sentence long!

Now, before you commit the faux pas of saying Opdycke should have looked harder, realize that he has been looking into early aviation for 50 years! (He even built and flew his own WWI biplane.) He is an educator by trade (el-hi to college) and as a fairly young man founded in 1961 an organization, World War I Aeroplanes Inc., to advance aviation history. It still exists and publishes two very good quarterly journals, WWI Aero: The Journal of the Early Aeroplane and Skyways: The Journal of the Aeroplane 1920–1940 which Opdyke published or edited for many years. Meaning? If he and his global army of contacts haven’t found it, chances are there’s nothing to find.

It should be noted that for the first five of the fifteen years it took to write this book French aviation historian Michel Bénichou was a collaborator until other professional duties intervened. He was for 30 years Editor in Chief of France’s oldest monthly aviation history magazine (now called Le Fana de L’Aviation, founded 1969) and has written a tall stack of aviation books.

Opdycke isn’t just an airplane geek but a connoisseur in that he appreciates the esthetic qualities as much as the mechanical ones. Without hard science or CAD or simulators at their disposal, the early inventors struggled to translate the adage “if it looks right it is right” into properly working machinery. Opdycke is sympathetic to that and his descriptions explain the people behind the work, references it to the then-prevailing thinking, and relates the aircraft’s operating features and specs. There is, incidentally, no Index so if you come across something noteworthy, mark it while you can . . . or never find it again. Some of the entries even have first-hand accounts of flight testing and other pertinent recollections. Over 800 b/w photos and a few drawings, all precisely captioned and credited, flesh out the story

There are many more facets to the story of French aviation that fall outside this book’s inquiry, the most pressing one being the questions why did it start here? and why didn’t it continue? The latter one has an easy answer, the first one not at all. Still, in all the years since its first publication it has not been bettered, nor has Opdycke himself entertained the urge to write more books.

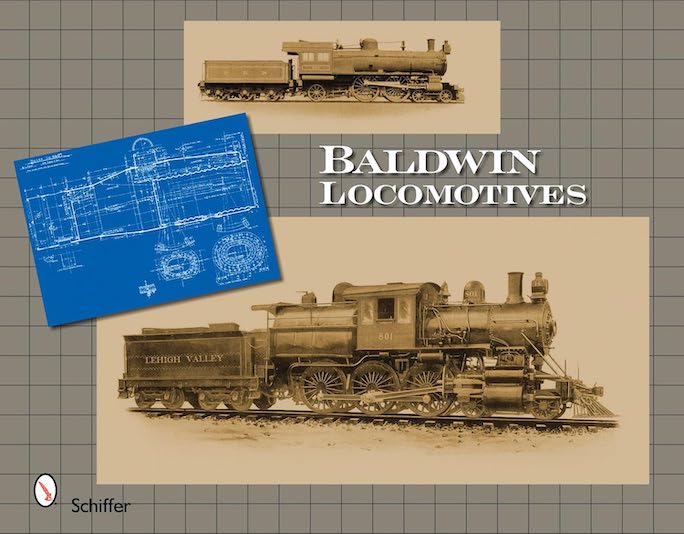

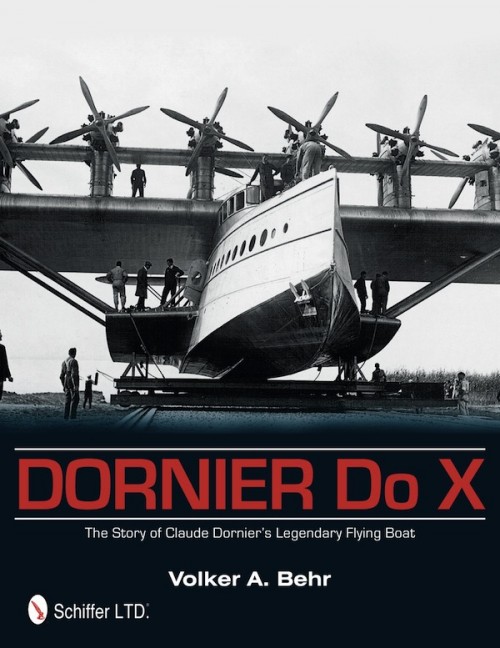

As so many Schiffer books, this one too has beautiful marbled endpapers, is printed on excellent paper, and in every respect will delight the bibliophile. Typesetting/proofreading are utterly impeccable.

There’s no reason why one wouldn’t read this book cover to cover but its long-term use will surely be that of an indispensable reference book. You’ll be surprised as much by the utterly exotic novelties people came up with (wind-up rubber-band “motor”) as by technologies and principles you’ll still find on today’s aircraft (delta wings etc.).

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter