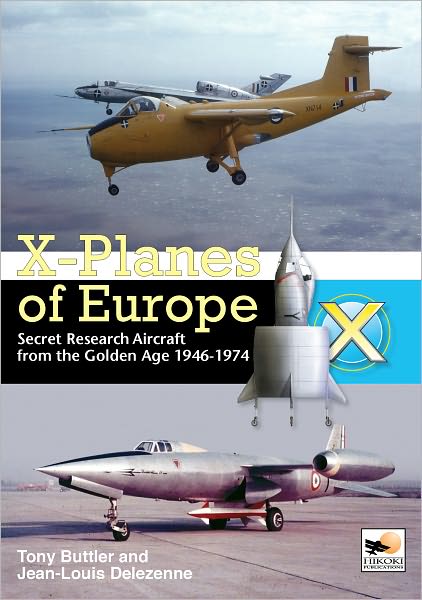

X-Planes of Europe: Secret Research Aircraft from the Golden Age 1947–1974

by Tony Buttler & Jean-Louis Delezenne

by Tony Buttler & Jean-Louis Delezenne

“And of course during this exciting time exceptional pilots risked their lives on a daily basis to test various experimental prototypes to their limits, and in so doing took calculated risks to ensure the safety of pilots of future production aircraft.”

“There’s an app for that!!” From preheating your Jacuzzi with a telephone call to remote-controlled robotic surgery to . . . flight testing, computers and simulators do today much that in the olden days required someone to actually go out and just do it. Many of the ideas tested on the aircraft shown here proved to be too impractical or unsuitable to result in adoption for production but some laid the groundwork for fundamental advances in aviation.

For readers who already own this publisher’s several other books about experimental and prototype aircraft, this fine book is an essential and unavoidable acquisition. (If Hikoki Publications ever were to do such a book about Japanese efforts it would  make their coverage of these important aviation stepping stones pretty much global.) That this book should find itself in the Hikoki line-up seems only natural but that’s not where this project was hatched. It had a positively rocky start—through no fault of its own—as is evident not least in the fact that its copyright was registered in 2010 but its publication date of record is mid-2012, and with a publisher different from the one that started the project. The only reason to mention this is to let those folks who all through 2011 perked up every time it looked as if a book with this name was about to get printed know that the wait is over: this Hikoki edition, now clocking in at 302 pages and with similar comprehensiveness to that of its companions, is that book.

make their coverage of these important aviation stepping stones pretty much global.) That this book should find itself in the Hikoki line-up seems only natural but that’s not where this project was hatched. It had a positively rocky start—through no fault of its own—as is evident not least in the fact that its copyright was registered in 2010 but its publication date of record is mid-2012, and with a publisher different from the one that started the project. The only reason to mention this is to let those folks who all through 2011 perked up every time it looked as if a book with this name was about to get printed know that the wait is over: this Hikoki edition, now clocking in at 302 pages and with similar comprehensiveness to that of its companions, is that book.

Containing many previously unpublished photos and now declassified information, this book presents Western European post-WWII aircraft. Of the 38 entries, most are British and French, two (West) German, and one each Swedish and Swiss.

The book does not explain this but authors Buttler and Delezenne did not physically collaborate on this project and had never met in the flesh (but had presumably known of each other)! It is the publisher who orchestrated this joint venture and put the various pieces of the puzzle together. Buttler’s name is of course long familiar to readers of this genre. A trained metallurgist he was directly involved in the testing of a number of aluminum and titanium airframes and components, and has turned his professional/private interest in design and development into a productive freelance career—18 books and countless magazine articles—as an aircraft historian. Delezenne, as you might gather from the name, is the French leg of this duo. If you read Wings or Airpower magazine, you may well recognize his name as an editor, contributor, and photographer. (Also, if you lived in the LA area in the 1990s you might remember him as a restauranteur, or, if you have anything to do with or in French Polynesia, as a tourism/transportation facilitator etc.) What he brings to this his first book is the French Connection to museums, archives (including his own), and aviation history. This, indeed, is of significance because as the Introduction says, “By comparison with the UK, French experimental programs did not receive the same archival coverage or preservation of information.” In fact, it is not just information that went unpreserved but actual hardware: only 6 of 15 French types vs. 13 of 19 British ones.

The Intro also paints a very relevant picture of the reasons the French aviation industry was forced onto such a different path during and after WWII. Considering the formidable odds it is all the more remarkable that France, which had played such a singular pioneering role in the development of aviation, was able to regain a position of importance. As one would expect of an Introduction it also lays out the criteria for what the book does and does not include (as always, nothing is simple . . .). Basically, it deals with “pure research” aircraft and excludes those that became actual production/service machines.

The 38 aircraft are covered in chronological order, irrespective of country although each entry shows the respective country’s flag. The only place this could conceivably be unsatisfactory is the Table of Contents where the reader would have to know, for instance, that VFW is a German and FAF a Swiss maker. To each entry are devoted several pages and photos (mostly b/w, large, clear, thoroughly captioned, and credited), occasionally augmented with 3-views (mostly without dimensions), color profile drawings, and the odd tech drawing or ad. Four (British) planes are shown on double-page b/w cutaways. All entries begin with a data panel of technical/performance specs for the main type/s covered and the text describes the role/purpose of the aircraft, design highlights, testing regimen etc. The level of magnification varies considerably; the focus is on context and overview rather than technical minutia.

Appended is a description of the French Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace (including address, directions), a table of surviving airframes, and a Glossary (including the names/abbreviations of the major French manufacturing centers). The Bibliography lists materials consulted; the Index is divided into aircraft and people.

Even the well-read aviation enthusiast will make discoveries in this beautifully made book, especially among the French aircraft!

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter