Batmobile: The Complete History

At least since the mid-1990s, The Batman has been subjected to academic inquiry and scrutiny. In 1996, The Many Lives of The Batman was published, a collection of “critical appraisals to a superhero and his meaning” that “represent many of the paradigms which constitute contemporary cultural studies.” Scholars from The University of Pennsylvania, Notre Dame, MIT, and the University of Arizona are represented. Will Brooker, in 2001, then an assistant professor of communications at The American International University in London, published Batman Unmasked/Analyzing a Cultural Icon, a book-length study, and this book, as a blurb extols, “is a well-researched history and an impressive tour of our culture’s fascination with a mythos in its populist midst.” So, for at least sixteen years, academics, through cultural studies, media studies, women’s studies, gay studies and the like, have researched, theorized and written dissertations on what basically began, in 1939, as a costumed cartoon character created for consumption by preadolescent boys. What happened? Why a book on The Batman’s ride?

Part of the answer lies in the mid-1960s when the divide between fine arts and popular arts frayed and blurred—think Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Crumb, Stanley Kubrick, and The Beatles. Also during this time period, The Batman, in the important works of the canon, dropped his young sidekick Robin and emerged as a sinister, brooding, conflicted crime fighter, often working at the edges if not outside of the legal system. The cast of supporting characters matured and developed, and through the subsequent decades the plotlines became dense, complex and centered on issues such as the drug trade, political graft and corruption, child molestation and organized crime. And the modern Batman films also matured (There are always exceptions; the George Clooney debacle is exceptionally bad.), culminating in the 21st century Dark Knight trilogy directed by Christopher Nolan that took the stories to the most believable, realistic plateau possible—considering the premise of the enterprise. This book devotes considerable attention to these films, focusing on The Tumbler, more Humvee than sports car, one of latest incarnations of The Batman’s crime-fighting road machines.

And it explores some but not all of The Tumbler’s progenitors, starting with the first comic book version, a supercharged red convertible, basically used to get The Batman and Robin from A to B. It is told that The Batman’s creator Bob Kane, visiting the movie set of the first movie serial, 1943, found to his dismay that the Batmobile was merely a contemporary Cadillac convertible. Two of the best-known Batmobiles have to be the comic book version introduced by the artist Dick Sprang in 1950 and virtually unchanged for over a decade, with its huge central fin, super-wide wrap-around windshield, interior mobile crime lab, and the daunting bat-faced front end; the second is the George Barris-built two-seater used in the 1966-through-1968 TV series and its spinoff movie. (This series, by the way, presented The Batman, accompanied by Robin, as comedic pop satire, a perhaps unwelcome interlude to the ominous crime fighter as mentioned above.) The jet-like 1980s movie car is documented in its various incarnations along with a string of comic book interpretations. What is missing, however, unaccountably, are the cars from the several Saturday morning animated television series.

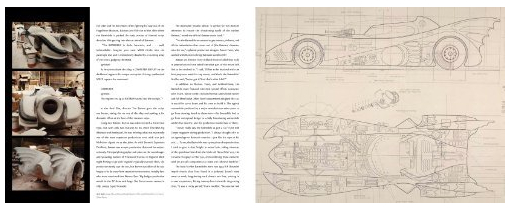

The running thesis throughout the book, and perhaps a more complete answer to those questions posed above, is that a Batmobile, whether on the page or on the screen, is both a character in its own right and an extension of The Batman himself. The machine exudes power and sex appeal. And what is quite interesting is the documentation, in text and in illustration, of the Batmobiles designed and built for the modern films that purposely dramatize these qualities. These are not computer-generated creations (although in the films digital enhancements are utilized), but rather actual, drivable automobiles capable of high speeds and surprising maneuverability. The Tumbler, for example, can be dropped from a great height and remain operable. Photographs of the various cockpits, rough like early Grand Prix cars or Bonneville speedsters, complete with gauges, seat belts, cages and controls, emphasize this point.

The book does not entirely neglect the other vehicles in The Batman’s arsenal. The Bat-gyro and the Batplane are mentioned in passing, and there is a still from the 1960s TV series of The Batman motoring through Gotham astride the Batcycle, Robin gamely braced in the sidecar. But the most intriguing and exhilarating of all of this gadgetry is the Bat-Pod: “After the Tumbler comes to a stop, the vehicle’s computer system scans the wreckage and reports: ‘Damage Catastrophic . . . Eject Sequence initiated.’ The Tumbler begins shaking, its front parts realign. ‘Goodbye,’ the computer’s audio sweetly says—and Batman bursts from the wreckage at the controls of the ‘Bat-Pod,’ a two-wheeler that retains the Tumbler’s firepower, while its sleek form allows him to zip in and out of traffic.” This concept, that the Tumbler has an escape pod, one that morphs into a cycle, I find exceeding clever. Batmobile offers “detailed production art” that “illustrates the Tumbler’s transformation to the Bat-Pod after it self-destructs,” and this sequence of illustrations, covering slightly more than one full page, is an example of the book’s attractive design.

The book does not entirely neglect the other vehicles in The Batman’s arsenal. The Bat-gyro and the Batplane are mentioned in passing, and there is a still from the 1960s TV series of The Batman motoring through Gotham astride the Batcycle, Robin gamely braced in the sidecar. But the most intriguing and exhilarating of all of this gadgetry is the Bat-Pod: “After the Tumbler comes to a stop, the vehicle’s computer system scans the wreckage and reports: ‘Damage Catastrophic . . . Eject Sequence initiated.’ The Tumbler begins shaking, its front parts realign. ‘Goodbye,’ the computer’s audio sweetly says—and Batman bursts from the wreckage at the controls of the ‘Bat-Pod,’ a two-wheeler that retains the Tumbler’s firepower, while its sleek form allows him to zip in and out of traffic.” This concept, that the Tumbler has an escape pod, one that morphs into a cycle, I find exceeding clever. Batmobile offers “detailed production art” that “illustrates the Tumbler’s transformation to the Bat-Pod after it self-destructs,” and this sequence of illustrations, covering slightly more than one full page, is an example of the book’s attractive design.

Cotta Vaz’s emphasis lies with the film cars, however, and this makes sense as he has built his career on books relating to cinema: Twilight: The Complete Illustrated Movie Companion, The Spirit: The Movie Visual Companion and The Adventures of Marian C. Cooper, Creator of King Kong are among them. His The Art of Star Wars: Episode II—Attack of the Clones is co-authored by George Lucas and Jonathon Hales. Lucas needs no introduction; Hales is a playwright and screenwriter who had worked with Lucasfilm and, with Lucas, wrote the screenplay for Clones. Provocative questions arise from these considerations: Is Cotta Vaz a bit too cozy with Warner Brothers and DC Comics? Is Batmobile yet another tie-in like the DC Direct Dark Knight action figures or the Dark Knight 1/25 scale model kits sold by Moebius? Because of the overall quality of the book, a third question, of a philosophical bent, arises: Does it matter? This is worth consideration, but even to approach a studied opinion, let along attempting a definitive answer, reaches far beyond the limitations of this review.

Cotta Vaz’s emphasis lies with the film cars, however, and this makes sense as he has built his career on books relating to cinema: Twilight: The Complete Illustrated Movie Companion, The Spirit: The Movie Visual Companion and The Adventures of Marian C. Cooper, Creator of King Kong are among them. His The Art of Star Wars: Episode II—Attack of the Clones is co-authored by George Lucas and Jonathon Hales. Lucas needs no introduction; Hales is a playwright and screenwriter who had worked with Lucasfilm and, with Lucas, wrote the screenplay for Clones. Provocative questions arise from these considerations: Is Cotta Vaz a bit too cozy with Warner Brothers and DC Comics? Is Batmobile yet another tie-in like the DC Direct Dark Knight action figures or the Dark Knight 1/25 scale model kits sold by Moebius? Because of the overall quality of the book, a third question, of a philosophical bent, arises: Does it matter? This is worth consideration, but even to approach a studied opinion, let along attempting a definitive answer, reaches far beyond the limitations of this review.

Although not indexed, Batmobile comes with source notes and Cotta Vaz’s 2012 interview with Paul Levitz and Nathan Crowley. Levitz, at the time of Batmobile’s publication, had “recently finished a thirty-eight year run at DC Comics as the company’s president and publisher,” while Crowley had worked as production designer for the Nolan films. Filling but two pages, the interview is neither deep nor particularly fulfilling, but Levitz does provide insight of the importance of The Batman’s automobiles as an integral component of the DC Comic/Batman universe, and Crowley’s reflections concerning the Tumbler’s gestation underscore Cotta Vaz’s thesis. Levitz: “The job of the car is to stay ahead of reality, and with the speed with which reality is changing these days, it’s hard to create plausible science fiction that sticks for a long time.” Crowley: “But to me there was always this fine-edged military sports car, Lamborghini feeling. I wanted to put femininity to it where the facets become curved, and I think that is when we started to crack it.”

Batmobile is neither an academic production nor gee-whiz fanzine adulation. The prose is that of an accomplished writer who finds his material worthy of adult appreciation and who is not reluctant to share his (preadolescent?) interest with the world. It is quite the handsome book, with its fold-out photographs, comic book reproductions (who can resist?), car designers’ plans, and movie stills. The endpapers show drawings of a variety of Batmobiles, and there was one particular design element that caught my eye and imagination: On page 37, notice the small Bat-logo, a silvery grey, practically white, nearly invisible from certain angles, illusive, a quite beautiful touch. And, please, don’t miss the Bill Sala painting on the penultimate page. It’s priceless.

Copyright 2012, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter