By Precision Into Power: A Bicentennial History of D. Napier

“Essentially, this book sets out to reveal and describe the outstanding influence of the personalities and products of the Napier Company over two centuries, in as much detail as our factual knowledge and space permit.”

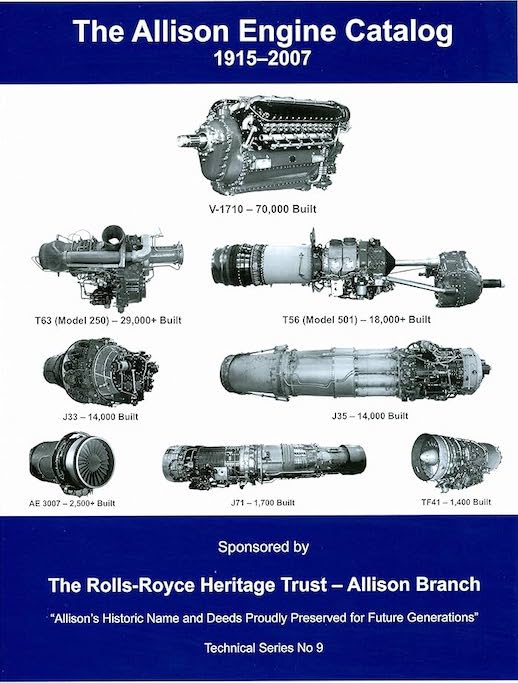

Depending on your interests, Napier means many things to many people. From fast and luxurious road and racing cars to some of the storied aircraft engines, this venerable British company also made printing presses, coin weighing and stamp perforating machines, a centrifuge for sugar manufacturing, lathes and drills, ammunition-making equipment, and all sorts of choice bits of precision engineering. Engine folks, whether auto, truck, aero, rail or ship will be able to rattle off any number of history-making powerplants at the drop of a hat. Several factories, several generations of Napiers, fame, fortune, records, 20,000 employees—all gone today except for a small spinoff that produces turbochargers for the marine, power, and rail industries. Obviously a story worth preserving and knowing.

Alan Vessey is a lifelong Napierian, having started as an apprentice in 1952 and spending his entire working life there and later as archivist of the Napier Power Heritage Trust. He has written several books on this important company but none of the scope of this one. Begun in 1990 and delayed more than once by the discovery of more and more archival material, its very detail may cause some readers’ eyes to glaze over but, really, thoroughness ought never to be thought a demerit.

Founded in 1808, Napier’s activities predate those of other firms by so much that the book will surely be an eye-opener to those readers more familiar with Napier’s rivals and peers. Rolls-Royce, a similarly storied and important company, needs to be particularly considered in this regard.

Vessey’s comprehensive history covers all this so we will here only focus on a few points that shed a different light on matters pertaining to aero and car engines to which are devoted two of the ten chapters: All previous documentation indicted that Arthur Rowledge, who later moved on to Rolls-Royce after a dispute, was responsible for the Lion aero engine’s design, the engine that won the Schneider Trophy for Britain. Although Vessey credits Rowledge with much of the development, he accords most of the credit to Montague Napier—this came as a surprise to this reviewer. The Lion also powered many land speed record cars (the ultimate being the Railton Special driven by John Cobb to a world speed record in 1947, a record that held until the mid 1960s) and speedboats. In 1931 both Napier and Rolls-Royce were in a bidding war for the bankrupt Bentley Motors and the dubious means by which Rolls-Royce captured control is briefly covered; reading between the lines one cannot help wondering how different the three companies would have fared if Napier had been the successful bidder. Moreover, and ironically, when Napier picked up the challenge of developing aero gas turbines in the immediate postwar years with limited success it was Rolls-Royce that took over the surviving programs.

As an aside, George Eyston’s Thunderbolt LSR car is described as being powered by the R-R Merlin when it really was an “R” engine.

The early 1930s are the Halford era in which Frank Halford acted as a consultant and designed the Rapier, Dagger, and Sabre engines. Having spent all of his career with Napier it is perhaps understandable that the author did not go into great detail about the Sabre’s woes and glosses over the assistance that Bristol gave (was forced to give?) for Sabre sleeve production. Development of a two-stage intercooled Sabre driving contra-rotating propellers offers fascinating insight as to where technology was heading. Of course this did not happen; instead Rolls-Royce developed their version known as the Eagle 22.

Postwar developments include the incredible Deltic two-stroke Diesel. Although never intended for aircraft propulsion it was built to aircraft standards with regard to precision and light weight. Nonstarters, such as the Nomad turbo compounded two-stroke aircraft Diesel, are also described. Entering the gas turbine field late in the game made it a tough chore for Napier to catch up even though the company produced some excellent engines. Reading between the lines it appears that the slow decline started after about the late 1950s. It was somewhat reminiscent of the decline of Wright Aeronautical. Finally in 1974 the name Napier disappeared and sadly these days few people have even heard of the name.

Appended are 33 pages of detailed listings of Napier products from 1815 to 1983. Index. This book is an excellent read and highly recommended.

Copyright 2013, Graham White/Mike Jolley (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter